| Latest Maths NCERT Books Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

Chapter 3 Number Play

This resource provides comprehensive solutions for the exercises found within Chapter 3, "Number Play" (sometimes referred to as "Playing with Numbers"), from the latest Class 6 Ganita Prakash textbook issued by NCERT for the academic session 2024-25. The core objective of this chapter is to explore the fascinating intrinsic properties and relationships that govern numbers. These solutions are meticulously designed to offer exhaustive guidance, helping students master fundamental concepts such as factors, multiples, the distinction between prime and composite numbers, and the highly practical divisibility rules.

Students engaging with this material will discover detailed, step-by-step methodologies for essential number theory tasks. This includes systematically finding all the factors of a given number and generating lists of its multiples. Understanding factors (numbers that divide a given number exactly) and multiples (numbers obtained by multiplying a given number by an integer) forms the bedrock for many subsequent mathematical topics. The solutions aim to clarify these foundational ideas, ensuring students can confidently identify and work with them.

A significant portion of the solutions is devoted to explaining and demonstrating the application of various tests for divisibility. These shortcuts are invaluable for simplifying calculations and gaining deeper insights into number properties. The solutions cover the rules for determining if a number is divisible by:

- 2

- 3 (checking if the sum of the digits is divisible by 3)

- 4

- 5

- 6 (checking divisibility by both 2 and 3)

- 8

- 9 (checking if the sum of the digits is divisible by 9)

- 10

- 11

Central to "Number Play" is the computation of the Highest Common Factor (HCF) and the Lowest Common Multiple (LCM) of two or more numbers. The solutions provide detailed illustrations of the primary methods used to find these values. Special attention is given to:

- Prime Factorization Method: This involves breaking down each number into its unique product of prime factors (e.g., expressing $12$ as $2 \times 2 \times 3$). The solutions carefully explain how to perform prime factorization and then use these factors to determine the HCF and LCM.

- Division Method: An alternative systematic process for finding HCF and LCM, which is also broken down into easy-to-follow steps within the solutions.

Furthermore, these solutions expertly tackle word problems that necessitate the practical application of HCF and LCM concepts. Examples include scenarios like finding the largest possible tile size to perfectly cover a rectangular floor (an HCF application) or determining when synchronised events, such as bells tolling together or runners meeting again at a starting point, will next occur (an LCM application). The solutions meticulously guide students in analyzing the problem statement to correctly identify whether the HCF or the LCM is required, followed by the execution of the appropriate calculation method. Studying these detailed solutions is crucial for students aiming to solidify their grasp of number theory fundamentals presented in the Class 6 Ganita Prakash (2024-25), significantly enhancing their computational skills and developing effective problem-solving strategies related to factors and multiples – abilities essential for all future mathematical endeavours.

Intext Question (Page 55 - 56)

Question: Think about various situations where we use numbers. List five different situations in which numbers are used. See what your classmates have listed, share, and discuss.

Answer:

Numbers are a very important part of our daily lives and we use them in almost everything we do. Here are five different situations where numbers are used:

1. Telling Time and Following a Schedule

We use numbers to read the time on a clock. For example, your school might start at 8:00 AM, your lunch break could be at 12:30 PM, and you might play for 2 hours in the evening. The numbers on the clock help us organize our entire day.

2. Shopping and Handling Money

When you go to a shop to buy a packet of biscuits for

3. Sports and Games

In sports like cricket, numbers are everywhere! We see the score, like 150 runs for 3 wickets. Players have numbers on their jerseys, like number 7 or number 18. In games, we keep track of points to see who is winning. Without numbers, it would be impossible to know the score.

4. Dates and Calendars

We use numbers to know the date. For example, your birthday might be on the 15th of a month, or Independence Day is celebrated on August 15th every year. The year itself, like 2024, is a number. Calendars use numbers to help us keep track of important days and events.

5. Cooking and Recipes

When someone cooks in the kitchen, they often follow a recipe that uses numbers. For example, a recipe might say to add 2 cups of flour, 1 teaspoon of sugar, and bake for 30 minutes at 180 degrees Celsius. These numbers ensure that the food tastes right every time.

A child says ‘1’ if there is only one taller child standing next to them.

A child says ‘2’ if both the children standing next to them are taller.

A child says ‘0’, if neither of the children standing next to them are taller.

That is each person says the number of taller neighbours they have.

Question: Try answering the questions below and share your reasoning:

1. Can the children rearrange themselves so that the children standing at the ends say ‘2’?

2. Can we arrange the children in a line so that all would say only 0s?

3. Can two children standing next to each other say the same number?

4. There are 5 children in a group, all of different heights. Can they stand such that four of them say ‘1’ and the last one says ‘0’? Why or why not?

5. For this group of 5 children, is the sequence 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 possible?

6. Is the sequence 0, 1, 2, 1, 0 possible? Why or why not?

7. How would you rearrange the five children so that the maximum number of children say ‘2’?

Answer:

These are interesting logic puzzles! Here is the reasoning for each question.

1. Can the children rearrange themselves so that the children standing at the ends say ‘2’?

No, this is impossible.

Reasoning: A child says ‘2’ only if both of the children standing next to them are taller. A child at either end of the line has only one neighbour. Since they don't have two neighbours, they can never have two taller neighbours. The maximum number a child at the end can say is ‘1’.

2. Can we arrange the children in a line so that all would say only 0s?

No, this is impossible (for a line of more than one child).

Reasoning: For every child to say ‘0’, they must have no taller neighbours. However, in any group of children with different heights, there is one child who is the tallest of all. The child standing next to this tallest person will always have one taller neighbour. Therefore, that child must say at least ‘1’, making it impossible for everyone to say ‘0’.

3. Can two children standing next to each other say the same number?

Yes, but only if they both say ‘1’.

Reasoning:

- They cannot both say ‘0’, because if Child A is next to Child B, for A to say '0', B must be shorter than A. But for B to say '0', A must be shorter than B, which is a contradiction.

- They cannot both say ‘2’ for the same reason (A must be shorter than B, and B must be shorter than A).

- However, they can both say ‘1’. Consider four children with heights 4, 3, 2, 1 (where 4 is the tallest) arranged in that order: (4, 3, 2, 1).

- The child with height 3 has a taller neighbour (4) and a shorter neighbour (2), so they say ‘1’.

- The child with height 2 has a taller neighbour (3) and a shorter neighbour (1), so they also say ‘1’.

4. There are 5 children in a group, all of different heights. Can they stand such that four of them say ‘1’ and the last one says ‘0’?

Yes, this is possible.

Reasoning: Arrange the children in order from tallest to shortest. For example, if their heights are 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1:

Arrangement: (5, 4, 3, 2, 1)

- The child with height 5 (tallest) has one shorter neighbour (4), so they say ‘0’.

- The child with height 4 has one taller neighbour (5) and one shorter neighbour (3), so they say ‘1’.

- The child with height 3 has one taller neighbour (4) and one shorter neighbour (2), so they say ‘1’.

- The child with height 2 has one taller neighbour (3) and one shorter neighbour (1), so they say ‘1’.

- The child with height 1 (shortest) has one taller neighbour (2), so they say ‘1’.

This arrangement gives the sequence of numbers: 0, 1, 1, 1, 1.

5. For this group of 5 children, is the sequence 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 possible?

No, this is not possible.

Reasoning: In any line of children, one child must be the tallest. Since this tallest child has no one taller than them, their neighbours will always be shorter. Therefore, the tallest child must always say ‘0’. It is impossible to have a line where no one says ‘0’.

6. Is the sequence 0, 1, 2, 1, 0 possible?

Yes, this is possible.

Reasoning: This sequence requires a specific arrangement of heights. Let the heights be 1 (shortest) to 5 (tallest). The following arrangement works:

Arrangement of heights: (4, 3, 1, 2, 5)

- Child 4: Neighbour (3) is shorter. Says ‘0’.

- Child 3: Neighbours are (4) and (1). One is taller. Says ‘1’.

- Child 1: Neighbours are (3) and (2). Both are taller. Says ‘2’.

- Child 2: Neighbours are (1) and (5). One is taller. Says ‘1’.

- Child 5: Neighbour (2) is shorter. Says ‘0’.

This arrangement successfully produces the sequence 0, 1, 2, 1, 0.

7. How would you rearrange the five children so that the maximum number of children say ‘2’?

The maximum number of children who can say ‘2’ is two.

Reasoning: A child who says ‘2’ must be in a "valley" (i.e., shorter than both neighbours). Two children standing next to each other cannot both be in a valley. Therefore, the children saying '2' must be separated by at least one other child. With five children, the best you can do is have two children saying '2' by alternating between taller and shorter children.

An arrangement that works (heights 1 to 5):

Arrangement of heights: (4, 1, 5, 2, 3)

- Child 4 says ‘0’.

- Child 1 has taller neighbours (4 and 5). Says ‘2’.

- Child 5 says ‘0’.

- Child 2 has taller neighbours (5 and 3). Says ‘2’.

- Child 3 says ‘0’.

This gives the sequence 0, 2, 0, 2, 0, with two children saying ‘2’.

Figure it Out (Page 57)

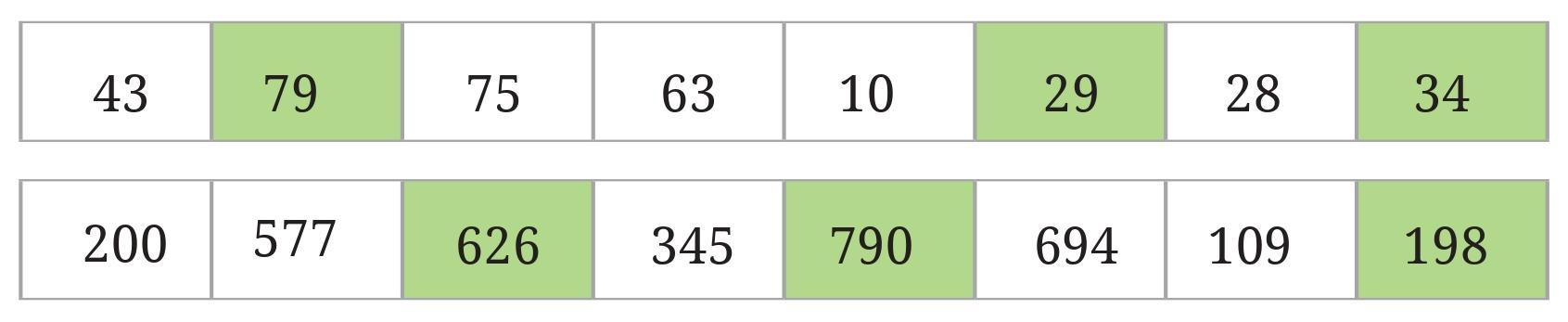

Supercells - A cell is coloured and called supercell if the number in it is larger than its adjacent cells.

626 is coloured as it is larger than 577 and 345 whereas 200 is not coloured as it is smaller than 577.

The number 198 is coloured as it has only one adjacent cell with 109 in it, and 198 is larger than 109.

Answer:

A "supercell" is a cell where the number inside it is larger than the number in each of its adjacent (neighbouring) cells. We need to check each number in the given table to see if it meets this condition.

Step-by-step analysis:

The given list of numbers is: [6828, 670, 9435, 3780, 3708, 7308, 8000, 5583, 52]

- 6828: This number is at the start, so it has only one neighbour, 670. Since 6828 > 670, 6828 is a supercell.

- 670: Its neighbours are 6828 and 9435. 670 is smaller than both of them, so it is not a supercell.

- 9435: Its neighbours are 670 and 3780. Since 9435 > 670 and 9435 > 3780, 9435 is a supercell.

- 3780: Its neighbours are 9435 and 3708. Since 3780 is smaller than 9435, it is not a supercell.

- 3708: Its neighbours are 3780 and 7308. 3708 is smaller than both of them, so it is not a supercell.

- 7308: Its neighbours are 3708 and 8000. Since 7308 is smaller than 8000, it is not a supercell.

- 8000: Its neighbours are 7308 and 5583. Since 8000 > 7308 and 8000 > 5583, 8000 is a supercell.

- 5583: Its neighbours are 8000 and 52. Since 5583 is smaller than 8000, it is not a supercell.

- 52: This number is at the end, so it has only one neighbour, 5583. Since 52 is smaller than 5583, it is not a supercell.

Result:

The supercells are 6828, 9435, and 8000. Here is the table with the supercells marked:

| 6828 | 670 | 9435 | 3780 | 3708 | 7308 | 8000 | 5583 | 52 |

Answer:

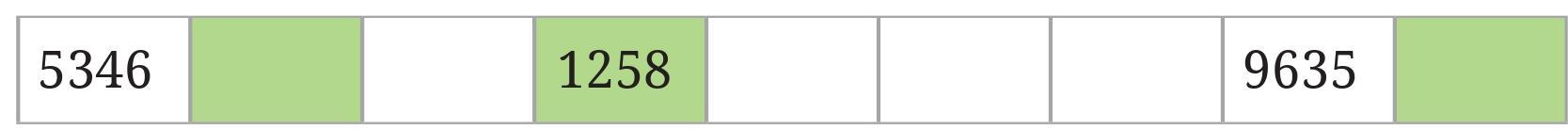

The goal is to create a sequence of nine 4-digit numbers where the 2nd, 4th, and 9th cells are "supercells". A supercell is a cell where the number inside it is larger than the number in each of its adjacent (neighbouring) cells.

The Correct Solution:

Based on your input, the correct sequence of numbers is:

| 5346 | 6000 | 1050 | 1258 | 1100 | 1200 | 1300 | 9635 | 9700 |

Verification of the Solution:

Let's check each cell to confirm that this solution is correct.

- Cell 1 (5346): Not a supercell because its neighbour (6000) is larger.

- Cell 2 (6000): Is a supercell because it is larger than both its neighbours, 5346 and 1050.

- Cell 3 (1050): Not a supercell because both its neighbours (6000 and 1258) are larger.

- Cell 4 (1258): Is a supercell because it is larger than both its neighbours, 1050 and 1100.

- Cell 5 (1100): Not a supercell because both its neighbours (1258 and 1200) are larger.

- Cell 6 (1200): Not a supercell because its neighbour (1300) is larger.

- Cell 7 (1300): Not a supercell because its neighbour (9635) is larger.

- Cell 8 (9635): Not a supercell because its neighbour (9700) is larger.

- Cell 9 (9700): Is a supercell because it is at the end and is larger than its only neighbour, 9635.

The solution perfectly matches the condition that only the 2nd, 4th, and 9th cells are supercells.

Answer:

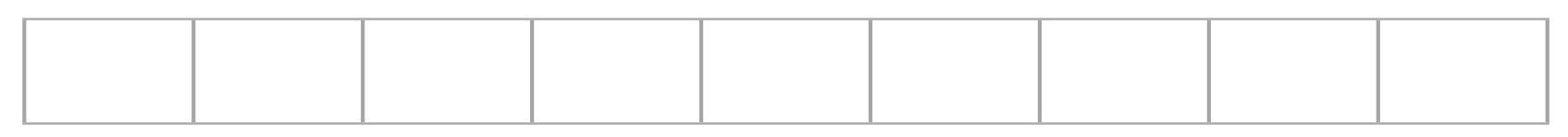

The goal is to fill the nine cells with unique numbers between 100 and 1000 to create the maximum possible number of "supercells". A supercell is a cell containing a number larger than its immediate neighbour(s).

Strategy to Maximize Supercells

To solve this, we need a strategy. Let's analyze the properties of a supercell:

- A supercell must be a "peak" in the number sequence, meaning it's higher than the numbers on its left and right.

- If a cell is a supercell, its immediate neighbors cannot be supercells. This is because a neighbor would have to be smaller than the supercell, but to be a supercell itself, it would need to be larger than its neighbors, which is a contradiction.

This means that supercells can never be adjacent to each other; they must be separated by at least one non-supercell. To get the most supercells in a row of nine, we should use an alternating pattern of high numbers (which will be our supercells) and low numbers (which will be the non-supercells).

The most efficient pattern is:

High, Low, High, Low, High, Low, High, Low, High

This pattern gives us a supercell in the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th positions, for a total of 5 supercells. This is the maximum possible number.

Solution:

Following this strategy, we can pick 5 large numbers and 4 small numbers (all unique and between 100 and 1000) and arrange them in the alternating pattern. Here is one possible solution:

| 950 | 110 | 940 | 120 | 930 | 130 | 920 | 140 | 910 |

Verification:

- 950 is a supercell because it's larger than its only neighbor (110).

- 940 is a supercell because it's larger than its neighbors (110 and 120).

- 930 is a supercell because it's larger than its neighbors (120 and 130).

- 920 is a supercell because it's larger than its neighbors (130 and 140).

- 910 is a supercell because it's larger than its only neighbor (140).

- All the low numbers (110, 120, 130, 140) are in "valleys" and are smaller than their neighbors, so they are not supercells.

This arrangement successfully creates 5 supercells, which is the maximum possible.

Question 4. Out of the 9 numbers, how many supercells are there in the table above? ___________

Answer:

Out of the 9 numbers, there are 5 supercells in the table above.

Reasoning:

This question refers to the table we created in Question 3 to maximize the number of supercells. The table was:

| 950 | 110 | 940 | 120 | 930 | 130 | 920 | 140 | 910 |

A supercell must be larger than its immediate neighbor(s). Let's check each cell:

- 950: Is larger than its only neighbor (110). It is a supercell.

- 110: Is smaller than its neighbors (950, 940). Not a supercell.

- 940: Is larger than its neighbors (110, 120). It is a supercell.

- 120: Is smaller than its neighbors (940, 930). Not a supercell.

- 930: Is larger than its neighbors (120, 130). It is a supercell.

- 130: Is smaller than its neighbors (930, 920). Not a supercell.

- 920: Is larger than its neighbors (130, 140). It is a supercell.

- 140: Is smaller than its neighbors (920, 910). Not a supercell.

- 910: Is larger than its only neighbor (140). It is a supercell.

Counting the supercells (950, 940, 930, 920, and 910), we find a total of 5.

Do you notice any pattern? What is the method to fill a given table to get the maximum number of supercells? Explore and share your strategy.

Let's explore the pattern for the maximum number of supercells possible in a single row of cells.

The most important rule to remember is that no two supercells can be next to each other. If Cell A is a supercell, it must be larger than its neighbor, Cell B. But if Cell B were also a supercell, it would have to be larger than Cell A, which is impossible. Supercells must be separated by at least one non-supercell.

The Pattern for a Single Row

Let's see how this rule affects rows of different lengths:

- 1 Cell: [ ]

The single cell has no neighbors, so it is automatically larger than all of them. Max Supercells = 1. - 2 Cells: [ | ]

The two cells are neighbors, so only one can be a supercell. We can make one by using a high and a low number (e.g., [200 | 150]). Max Supercells = 1. - 3 Cells: [ | | ]

We can place supercells in the 1st and 3rd positions, separated by a non-supercell (e.g., [300 | 100 | 290]). Max Supercells = 2. - 4 Cells: [ | | | ]

We can place supercells in the 1st and 3rd positions (or 2nd and 4th). (e.g., [400 | 100 | 390 | 110]). Max Supercells = 2. - 5 Cells: [ | | | | ]

We can place supercells in the 1st, 3rd, and 5th positions. (e.g., [500 | 100 | 490 | 110 | 480]). Max Supercells = 3.

Here is the pattern in a table:

| Number of Cells in the Row (n) | Maximum Possible Supercells |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 3 |

| 6 | 3 |

| 7 | 4 |

The pattern is: the maximum number of supercells is the total number of cells divided by 2, and then rounded up if there is a fraction. The mathematical formula for this is $\lceil \frac{n}{2} \rceil$.

Method to Get the Maximum Number of Supercells

The strategy is to create an alternating pattern of "peaks" (high numbers) and "valleys" (low numbers).

1. Identify Supercell Positions: To get the most supercells, choose the alternating positions starting from the very first cell: 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and so on.

2. Choose High and Low Numbers: Select two groups of numbers. The "High Group" will be for your supercells, and the "Low Group" will be for the cells in between. The smallest number in your High Group must be greater than the largest number in your Low Group.

3. Fill the Row: Place the numbers from the High Group into the supercell positions (1st, 3rd, 5th...) and the numbers from the Low Group into the remaining positions (2nd, 4th, 6th...).

Example for a 9-cell row:

Maximum supercells = $\lceil \frac{9}{2} \rceil = 5$. We need 5 high numbers and 4 low numbers.

- High Group: {910, 920, 930, 940, 950}

- Low Group: {110, 120, 130, 140}

The filled table would be:

| 950 | 110 | 940 | 120 | 930 | 130 | 920 | 140 | 910 |

This method guarantees that every number in a "peak" position is larger than its "valley" neighbors, thus creating the maximum number of supercells.

No, it is not possible to fill a table with unique numbers and have no supercells.

Reasoning:

In any collection of different numbers, there must be one number that is the largest of all. Let's call this number $N_{max}$.

Consider the cell in the table that contains this largest number, $N_{max}$. This cell has some neighbors (unless the table is only 1x1, in which case the single cell is a supercell by default).

By definition, $N_{max}$ is larger than every other number in the table. Therefore, it is also larger than the numbers in all of its adjacent cells.

According to the rule, a supercell is a cell whose number is larger than its neighbors. Since the cell with $N_{max}$ is larger than all of its neighbors, it will always be a supercell.

Because there is always at least one supercell (the one with the largest number), it is impossible to have a table with zero supercells.

Yes, the cell with the largest number in a table with unique numbers will always be a supercell.

Reasoning: The largest number in the entire table is, by definition, greater than every other number. This means it is automatically greater than the numbers in its immediate neighboring cells. Since it is larger than all its neighbors, it perfectly fits the definition of a supercell.

Part 2: Can the cell having the smallest number be a supercell?

No, the cell with the smallest number cannot be a supercell (unless the table has only one cell).

Reasoning: For a cell to be a supercell, its number must be larger than its neighbors. The smallest number in the entire table is, by definition, smaller than every other number. Therefore, it will be smaller than all of its neighbors. This is the exact opposite of the requirement for a supercell.

This is possible to do. The key is to understand what prevents a cell from being a supercell.

The Goal

Our goal is to arrange a set of unique numbers in a table so that the cell containing the second-largest number does not qualify as a supercell.

The Key Idea (Strategy)

1. A cell is a supercell if it is larger than ALL of its neighbors.

2. Therefore, to make a cell NOT a supercell, it only needs to have at least ONE neighbor that is larger than it.

3. Let's think about the second-largest number. What is the only number in the entire table that is larger than it? The absolute largest number.

4. So, the strategy is simple: place the second-largest number immediately next to the largest number. This guarantees it has a bigger neighbor, preventing it from being a supercell.

An Example in Action (1x5 Row Table)

Let's use the numbers {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}.

- The largest number is 5.

- The second-largest number is 4.

According to our strategy, we must place the number 4 next to the number 5. The other numbers (1, 2, 3) can fill the remaining spots. Here is one possible arrangement:

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

Verification

Let's check the cell with the second-largest number, which is 4.

- Its neighbors are 5 and 2.

- Is 4 larger than ALL its neighbors? No, because 4 is smaller than 5.

Since the cell with the number 4 has a larger neighbor, it is not a supercell. The condition has been successfully met.

Yes, this is possible, but it requires a very specific and clever arrangement of the numbers.

Analyzing the Conditions

We need to break down the two requirements to understand the puzzle's constraints.

1. How to make the second-smallest number a SUPERCELL:

- For a cell to be a supercell, it must be larger than all its neighbors.

- Let's consider the second-smallest number. The only number smaller than it in the entire table is the absolute smallest number.

- Therefore, for the second-smallest number to be a supercell, its neighbor(s) can only be the smallest number. This means it must have exactly one neighbor, and that neighbor must contain the smallest number. The only way for a cell to have just one neighbor is to be at the very end of a row or column.

2. How to make the second-largest number NOT a supercell:

- For a cell to *not* be a supercell, it must have at least one neighbor that is larger than it.

- Let's consider the second-largest number. The only number in the entire table larger than it is the absolute largest number.

- Therefore, to prevent the second-largest number from being a supercell, it must be placed next to the largest number.

The Combined Strategy

To satisfy both conditions, we need to create an arrangement where:

1. The second-smallest number is at one end of a row, with the smallest number right next to it.

2. The second-largest number is somewhere else in the row, right next to the largest number.

An Example in Action (1x4 Row Table)

Let's use the simplest set of four unique numbers: {1, 2, 3, 4}.

- Smallest number = 1

- Second-smallest number = 2

- Second-largest number = 3

- Largest number = 4

Following our strategy, we construct the row:

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

Verification

- Checking the second-smallest (2): It is at the end of the row. Its only neighbor is 1. Since 2 > 1, the cell with the number 2 is a supercell. (Condition is met).

- Checking the second-largest (3): It is next to the number 4. Since 3 is smaller than its neighbor 4, it is not a supercell. (Condition is met).

This arrangement successfully fulfills both requirements of the puzzle.

Here are two fun variations of the Supercell puzzle to challenge your friends:

Variation 1: The "Subcell" Puzzle

New Rule: A cell is called a "subcell" if its number is smaller than all of its neighbors.

Challenge: Fill a 3x3 grid with the numbers 1 through 9 so that you create the maximum possible number of subcells. How many can you make? (The strategy is similar to supercells, but you'll use low numbers instead of high ones!)

Variation 2: The "Plateau" Puzzle

New Rule: A cell is called a "plateau" if its number is larger than or equal to all of its neighbors. This allows you to repeat numbers!

Challenge: Fill a 1x7 row of cells using numbers between 1 and 5 (you can repeat numbers). Can you create exactly three plateaus?

Intext Question (Page 58 - 59)

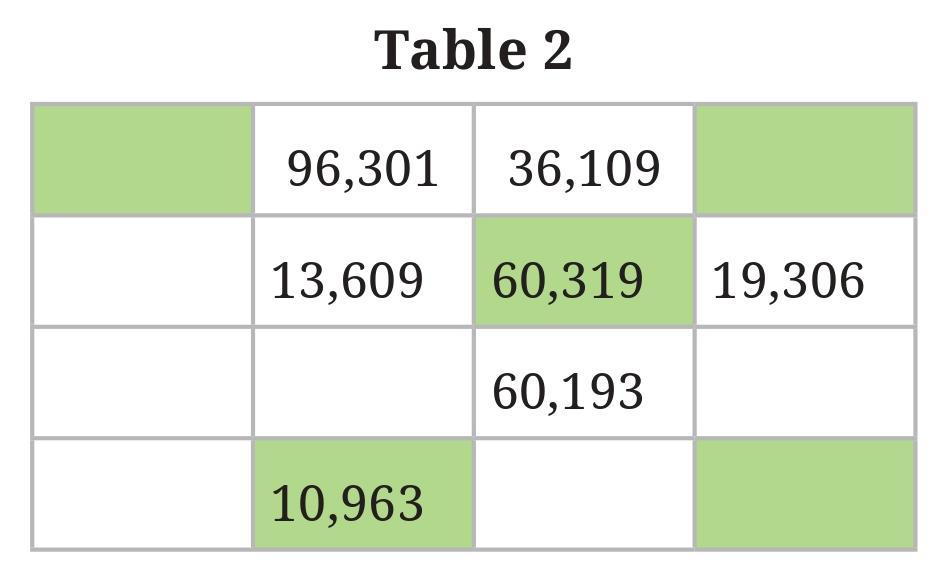

Question: Complete Table 2 with 5-digit numbers whose digits are ‘1’, ‘0’, ‘6’, ‘3’, and ‘9’ in some order. Only a coloured cell should have a number greater than all its neighbours.

The biggest number in the table is ____________ .

The smallest even number in the table is ____________.

The smallest number greater than 50,000 in the table is ____________.

Once you have filled the table above, put commas appropriately after the thousands digit.

Answer:

We need to fill the nine blank cells in the 4x4 grid using unique 5-digit numbers formed from the digits '1', '0', '6', '3', and '9'. The completed table must satisfy the specific supercell requirements you listed.

Here is one possible solution that correctly fills the table according to all the rules:

The Completed Table 2:

| 96,310 | 96,301 | 36,109 | 93,610 |

| 93,160 | 13,609 | 60,319 | 19,306 |

| 91,630 | 10,369 | 60,193 | 13,096 |

| 10,396 | 10,963 | 10,639 | 91,360 |

Verification of Supercells:

- (1, 1) = 96,310: Is a supercell because it's > 96,301 (right) and > 93,160 (bottom).

- (1, 4) = 93,610: Is a supercell because it's > 36,109 (left) and > 19,306 (bottom).

- (2, 3) = 60,319: Is a supercell because it's > 36,109 (top), > 13,609 (left), > 19,306 (right), and > 60,193 (bottom).

- (4, 2) = 10,963: Is a supercell because it's > 10,369 (top), > 10,396 (left), and > 10,639 (right).

- (4, 4) = 91,360: Is a supercell because it's > 13,096 (top) and > 10,639 (left).

All other cells have at least one larger neighbor, so they are not supercells. The solution is correct.

Step 2: Answering the Questions

Now, based on the completed table above:

The biggest number in the table is 96,310.

The smallest even number in the table is 10,396.

(The even numbers are those ending in 0 or 6. They are: 96,310, 93,610, 19,306, 13,096, 10,396, and 91,360. The smallest of these is 10,396).

The smallest number greater than 50,000 in the table is 60,193.

(The numbers greater than 50,000 are 96,310, 96,301, 93,610, 93,160, 60,319, 60,193, 91,630, and 91,360. The smallest among these is 60,193).

Figure it Out (Page 59)

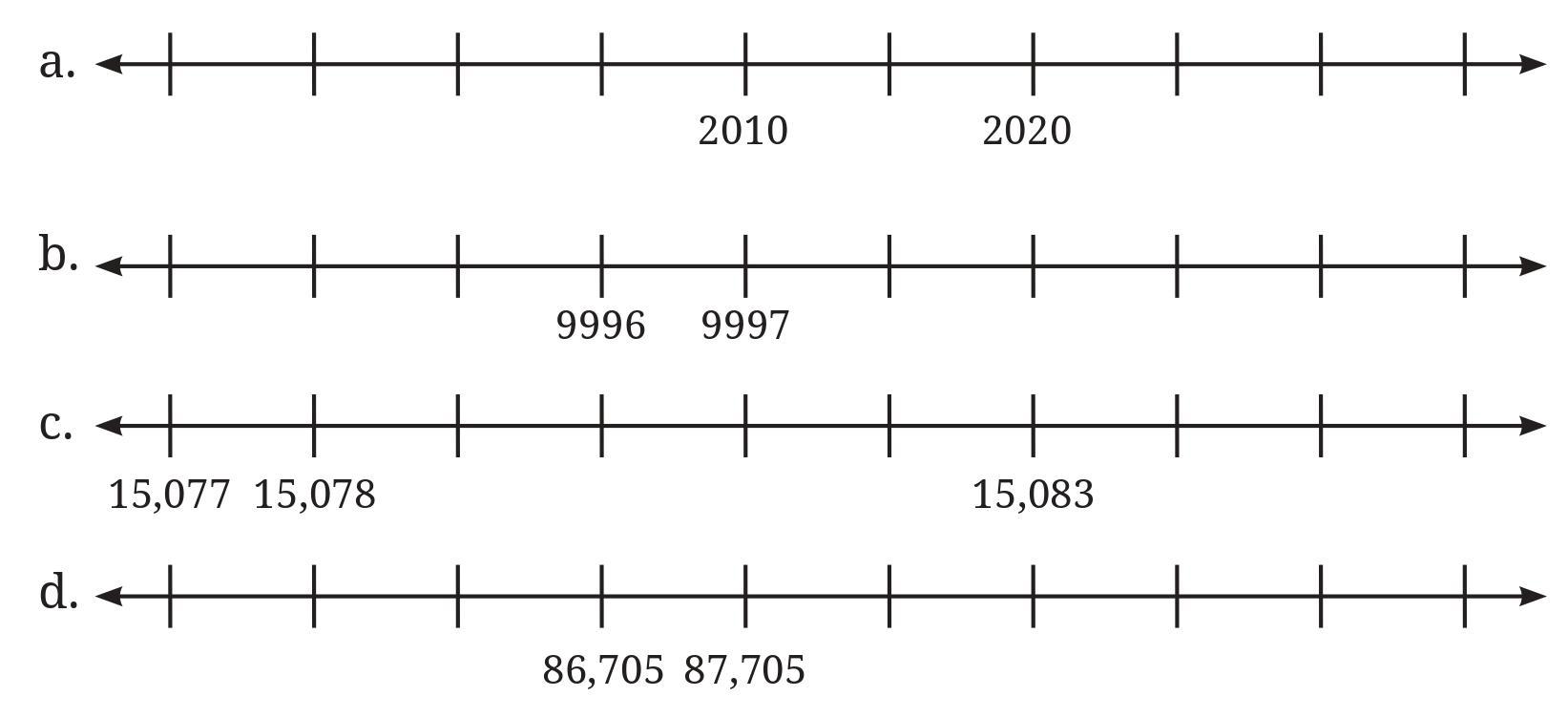

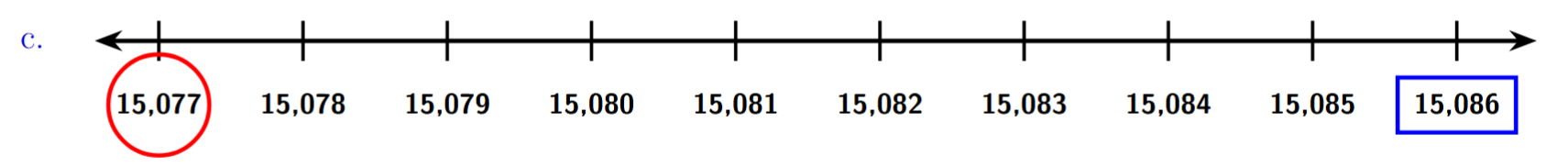

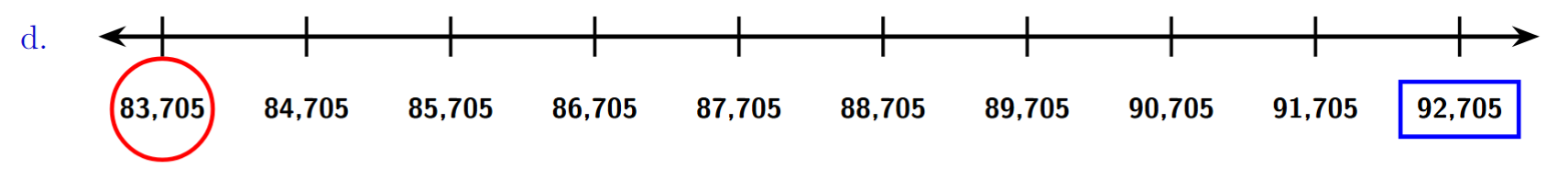

Put a circle around the smallest number and a box around the largest number in each of the sequences above.

Answer:

To solve this, we first need to figure out the "step" or "jump" size between each mark on the number lines. Then we can fill in the missing numbers and identify the smallest and largest.

a.

Identifying the step size: We see the numbers 2010 and 2020. The distance between them is $2020 - 2010 = 10$. There are two jumps between these numbers on the line. So, each jump is worth $10 \div 2 = 5$. The numbers increase by 5 at each step.

Completed Number Line:

Smallest Number: 1990

Largest Number: 2035

b.

Identifying the step size: We see two consecutive numbers, 9996 and 9997. The difference is 1. Since they are one jump apart, the numbers increase by 1 at each step.

Completed Number Line:

Smallest Number: 9993

Largest Number: 10002

c.

Identifying the step size: We see the numbers 15,077 and 15,078. The difference is 1. Since they are one jump apart, the numbers increase by 1 at each step.

Completed Number Line:

Smallest Number: 15,077

Largest Number: 15,086

d.

Identifying the step size: We see the numbers 86,705 and 87,705. The difference between them is $87,705 - 86,705 = 1000$. Since they are one jump apart, the numbers increase by 1000 at each step.

Completed Number Line:

Smallest Number: 83,705

Largest Number: 92,705

Intext Question (Page 60)

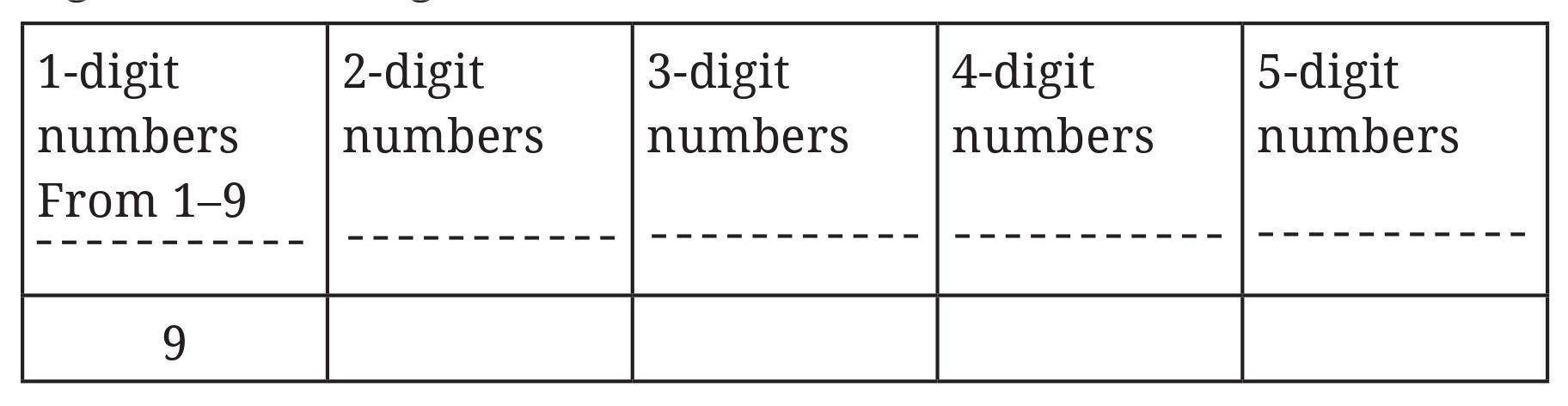

Answer:

To find out how many numbers have a certain number of digits, we can find the range of those numbers and then calculate the total count. Here is the completed table followed by the explanation.

Completed Table

| 1-digit numbers From 1–9 |

2-digit numbers From 10–99 |

3-digit numbers From 100–999 |

4-digit numbers From 1,000–9,999 |

5-digit numbers From 10,000–99,999 |

| 9 | 90 | 900 | 9,000 | 90,000 |

How to find the numbers:

There is a simple method to calculate the count for each category.

For 2-digit numbers:

The smallest 2-digit number is 10 and the largest is 99. To find the count, we can subtract the largest 1-digit number from the largest 2-digit number.

Count = (Largest 2-digit number) - (Largest 1-digit number) = $99 - 9 = 90$.

So, there are 90 two-digit numbers.

For 3-digit numbers:

The smallest 3-digit number is 100 and the largest is 999. We use the same method.

Count = (Largest 3-digit number) - (Largest 2-digit number) = $999 - 99 = 900$.

So, there are 900 three-digit numbers.

For 4-digit numbers:

The smallest 4-digit number is 1,000 and the largest is 9,999.

Count = (Largest 4-digit number) - (Largest 3-digit number) = $9,999 - 999 = 9,000$.

So, there are 9,000 four-digit numbers.

For 5-digit numbers:

The smallest 5-digit number is 10,000 and the largest is 99,999.

Count = (Largest 5-digit number) - (Largest 4-digit number) = $99,999 - 9,999 = 90,000$.

So, there are 90,000 five-digit numbers.

Figure it Out (Page 60)

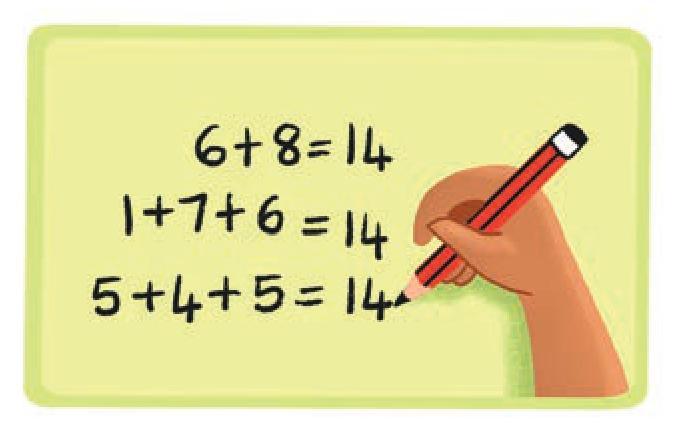

Adding the digits of the number 68 will be same as adding the digits of 176 or 545.

Question 1. Digit sum 14

a. Write other numbers whose digits add up to 14.

b. What is the smallest number whose digit sum is 14?

c. What is the largest 5-digit whose digit sum is 14?

d. How big a number can you form having the digit sum 14? Can you make an even bigger number?

Answer:

We are looking for numbers where the sum of their individual digits equals 14.

a. Write other numbers whose digits add up to 14.

There are countless numbers whose digits add up to 14. Here are some examples:

- 2-digit numbers: 59 ($5+9=14$), 68 ($6+8=14$), 77 ($7+7=14$), 86 ($8+6=14$), 95 ($9+5=14$).

- 3-digit numbers: 149 ($1+4+9=14$), 239 ($2+3+9=14$), 545 ($5+4+5=14$).

- 4-digit numbers: 1049 ($1+0+4+9=14$), 2057 ($2+0+5+7=14$), 3128 ($3+1+2+8=14$).

b. What is the smallest number whose digit sum is 14?

To find the smallest number, we should use the fewest digits possible. A 1-digit number can have a maximum sum of 9, so we need at least a 2-digit number.

To make a 2-digit number as small as possible, its first digit (the tens digit) must be as small as possible. To get a sum of 14, if we make the units digit as large as possible (which is 9), the tens digit would be:

$14 - 9 = 5$

This gives us the number 59. Any other 2-digit number (like 68) would be larger. Any number with more digits (like 149) will also be larger than 59.

The smallest number whose digit sum is 14 is 59.

c. What is the largest 5-digit whose digit sum is 14?

To find the largest number, we want the biggest digits possible in the leftmost places (the highest place values).

For a 5-digit number, we start from the ten thousands place:

- Put the largest possible digit, 9, in the ten thousands place. The remaining sum needed is $14 - 9 = 5$.

- Put the largest possible digit for the remaining sum, 5, in the thousands place. The remaining sum is $5 - 5 = 0$.

- The rest of the digits must be 0.

So, the digits are 9, 5, 0, 0, 0. Arranging them to make the largest number gives 95,000.

The largest 5-digit number whose digit sum is 14 is 95,000.

d. How big a number can you form having the digit sum 14? Can you make an even bigger number?

There is no limit to how big a number you can form.

You can take any number whose digits sum to 14 (like 59) and make it bigger by adding zeros to the end. The sum of the digits does not change.

For example: $5+9=14$, $5+9+0=14$, $5+9+0+0=14$.

- 59

- 590

- 5,900

- 59,000

You can always make an even bigger number by adding another zero. This can go on forever. So, there is no "biggest" number with a digit sum of 14.

Question 2. Find out the digit sums of all the numbers from 40 to 70. Share your observations with the class.

Answer:

Here are the digit sums for all the numbers from 40 to 70.

Table of Digit Sums

| Number | Digit Sum | Number | Digit Sum | Number | Digit Sum | ||

| 40 | 4 | 50 | 5 | 60 | 6 | ||

| 41 | 5 | 51 | 6 | 61 | 7 | ||

| 42 | 6 | 52 | 7 | 62 | 8 | ||

| 43 | 7 | 53 | 8 | 63 | 9 | ||

| 44 | 8 | 54 | 9 | 64 | 10 | ||

| 45 | 9 | 55 | 10 | 65 | 11 | ||

| 46 | 10 | 56 | 11 | 66 | 12 | ||

| 47 | 11 | 57 | 12 | 67 | 13 | ||

| 48 | 12 | 58 | 13 | 68 | 14 | ||

| 49 | 13 | 59 | 14 | 69 | 15 | ||

| 70 | 7 |

Observations:

- The sum increases by 1: As we count up from one number to the next (e.g., from 40 to 41, or 55 to 56), the digit sum usually increases by exactly 1. This happens because the units digit increases by 1 while the tens digit stays the same.

- The big drop: There is a big drop in the digit sum whenever we cross a multiple of 10. For example:

- From 49 (sum = 13) to 50 (sum = 5), the sum drops.

- From 59 (sum = 14) to 60 (sum = 6), the sum drops.

- From 69 (sum = 15) to 70 (sum = 7), the sum drops.

- Repeating Pattern: The digit sums follow a repeating "climb and drop" pattern. They climb from 4 to 13, drop to 5, climb to 14, drop to 6, and so on.

Question 3. Calculate the digit sums of 3-digit numbers whose digits are consecutive (for example, 345). Do you see a pattern? Will this pattern continue?

Answer:

Let's find the digit sums for 3-digit numbers made from consecutive digits and look for a pattern.

Calculating the Digit Sums

The possible sets of three consecutive digits are:

- {0, 1, 2}: Digit sum = $0+1+2=3$. (e.g., 102, 210)

- {1, 2, 3}: Digit sum = $1+2+3=6$. (e.g., 123, 321)

- {2, 3, 4}: Digit sum = $2+3+4=9$. (e.g., 234, 432)

- {3, 4, 5}: Digit sum = $3+4+5=12$. (e.g., 345, 543)

- {4, 5, 6}: Digit sum = $4+5+6=15$. (e.g., 456, 654)

- {5, 6, 7}: Digit sum = $5+6+7=18$. (e.g., 567, 765)

- {6, 7, 8}: Digit sum = $6+7+8=21$. (e.g., 678, 876)

- {7, 8, 9}: Digit sum = $7+8+9=24$. (e.g., 789, 987)

The next set would be {8, 9, 10}, but 10 is not a single digit, so the list stops here.

The Pattern:

The sequence of possible digit sums is: 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24.

There are two clear patterns:

- Each sum in the sequence is 3 more than the one before it.

- All the sums are multiples of 3.

Will this pattern continue?

Yes, the logic behind the pattern will continue, but the sequence of numbers itself has an end.

The reason the sums are always multiples of 3 is that the sum of any three consecutive numbers is always a multiple of 3. For any starting number $d$, the sum is:

$d + (d+1) + (d+2) = 3d + 3$, which is always divisible by 3.

The pattern of the sums increasing by 3 also continues because when we move from one set of digits (like {1,2,3}) to the next ({2,3,4}), each digit increases by 1, so the total sum increases by $1+1+1=3$.

However, the list of possible 3-digit numbers with consecutive digits ends when we reach the digits {7, 8, 9}, so the sequence of sums stops at 24.

Intext Question (Page 61)

Question 1: Among the numbers 1–100, how many times will the digit ‘7’ occur? Among the numbers 1–1000, how many times will the digit ‘7’ occur?

Answer:

Let's count the occurrences of the digit '7' in the given ranges by checking each place value.

Part 1: Counting the digit ‘7’ from 1 to 100

We can count the number of times ‘7’ appears in the units place and the tens place.

1. ‘7’ in the units place:

The digit ‘7’ appears in the units place for the following numbers:

7, 17, 27, 37, 47, 57, 67, 77, 87, 97

Counting these, we find that the digit ‘7’ occurs 10 times in the units place.

2. ‘7’ in the tens place:

The digit ‘7’ appears in the tens place for the following numbers:

70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79

Counting these, we find that the digit ‘7’ occurs 10 times in the tens place.

Total Occurrences:

To find the total number of times the digit ‘7’ occurs, we add the counts from both place values:

Total = (Occurrences in units place) + (Occurrences in tens place)

Total = $10 + 10 = 20$

Therefore, among the numbers 1–100, the digit ‘7’ occurs 20 times.

Part 2: Counting the digit ‘7’ from 1 to 1000

We can find the count by looking at the numbers from 1 to 999, as the number 1000 does not contain the digit ‘7’. Let's consider all numbers as 3-digit numbers from 000 to 999.

1. ‘7’ in the units place (e.g., 007, 017, 127):

In every set of 100 numbers (0-99, 100-199, etc.), the units digit ‘7’ appears 10 times. Since there are 10 such sets from 0 to 999, the total count is:

$10 \times 10 = 100$ times.

2. ‘7’ in the tens place (e.g., 070-079, 170-179):

In every set of 100 numbers, the numbers where the tens digit is 7 (the 'seventies') occur 10 times (e.g., 70, 71,...79). Since there are 10 such sets from 0 to 999, the total count is:

$10 \times 10 = 100$ times.

3. ‘7’ in the hundreds place (e.g., 700-799):

The digit ‘7’ appears in the hundreds place for all numbers from 700 to 799. The total count of these numbers is 100.

Total count = 100 times.

Total Occurrences:

Total = (Units place) + (Tens place) + (Hundreds place)

Total = $100 + 100 + 100 = 300$

Therefore, among the numbers 1–1000, the digit ‘7’ occurs 300 times.

Question 2: Write all possible 3-digit palindromes using these digits.

Answer:

The question does not specify which digits to use. We will assume the question means to use the standard set of digits from 0 to 9.

A palindrome is a number that reads the same forwards and backward. A 3-digit palindrome has the form where the first and last digits are the same. We can represent this as $aba$.

Rules for a 3-digit palindrome $aba$:

- The first digit, 'a', cannot be 0, otherwise it would not be a 3-digit number. So, 'a' can be any digit from 1 to 9.

- The middle digit, 'b', can be any digit from 0 to 9.

Finding all possible palindromes:

There are 9 possible choices for the digit 'a' (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

There are 10 possible choices for the digit 'b' (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

The total number of 3-digit palindromes is the number of choices for 'a' multiplied by the number of choices for 'b'.

Total Palindromes = $9 \times 10 = 90$.

Here is a list of all 90 possible 3-digit palindromes:

| Starting with 1 | Starting with 2 | Starting with 3 | Starting with 4 | Starting with 5 |

| 101 | 202 | 303 | 404 | 505 |

| 111 | 212 | 313 | 414 | 515 |

| 121 | 222 | 323 | 424 | 525 |

| 131 | 232 | 333 | 434 | 535 |

| 141 | 242 | 343 | 444 | 545 |

| 151 | 252 | 353 | 454 | 555 |

| 161 | 262 | 363 | 464 | 565 |

| 171 | 272 | 373 | 474 | 575 |

| 181 | 282 | 383 | 484 | 585 |

| 191 | 292 | 393 | 494 | 595 |

| Starting with 6 | Starting with 7 | Starting with 8 | Starting with 9 | |

| 606 | 707 | 808 | 909 | |

| 616 | 717 | 818 | 919 | |

| 626 | 727 | 828 | 929 | |

| 636 | 737 | 838 | 939 | |

| 646 | 747 | 848 | 949 | |

| 656 | 757 | 858 | 959 | |

| 666 | 767 | 868 | 969 | |

| 676 | 777 | 878 | 979 | |

| 686 | 787 | 888 | 989 | |

| 696 | 797 | 898 | 999 |

Intext Question (Page 62)

Question:

Explore

Will reversing and adding numbers repeatedly, starting with a 2-digit number, always give a palindrome? Explore and find out.

Answer:

This is a very interesting mathematical puzzle! Let's explore it by trying the "reverse and add" method on a few 2-digit numbers.

The process is:

1. Take a number.

2. Reverse its digits to get a new number.

3. Add the two numbers together.

4. If the result is not a palindrome (a number that reads the same forwards and backward), repeat the process with the new number.

Example 1: Starting with the number 48

Step 1:

The number is 48. Its reverse is 84.

Let's add them:

$\begin{array}{cc} & & 4 & 8 \\ + & & 8 & 4 \\ \hline & 1 & 3 & 2 \\ \hline \end{array}$

The result is 132, which is not a palindrome.

Step 2:

Now we use 132. Its reverse is 231.

Let's add them:

$\begin{array}{cc} & 1 & 3 & 2 \\ + & 2 & 3 & 1 \\ \hline & 3 & 6 & 3 \\ \hline \end{array}$

The result is 363. Since 363 reads the same forwards and backward, it is a palindrome! It took 2 steps for the number 48.

Example 2: Starting with the number 89

Some numbers take many more steps. Let's try 89.

Step 1: $89 + 98 = 187$

Step 2: $187 + 781 = 968$

Step 3: $968 + 869 = 1837$

Step 4: $1837 + 7381 = 9218$

... and so on.

This process continues for many steps. After a total of 24 steps, it finally becomes the palindrome 8,813,200,023,188.

Conclusion: Does it always work?

This question is a famous one in mathematics!

For the specific case of 2-digit numbers, people have used computers to test every single one from 10 to 99. The answer is yes, every 2-digit number has been found to eventually produce a palindrome through this process.

However, it's important to know that this is not proven for all numbers in general. There are some larger numbers that mathematicians suspect might never form a palindrome, no matter how many times you repeat the process. The first and most famous of these is the number 196. Even after millions of steps performed by computers, 196 has not yet produced a palindrome.

So, to answer the question: For all 2-digit numbers, it appears the answer is yes, but for numbers in general, it is a famous unsolved puzzle!

Intext Question (Page 62)

Question: Puzzle time

I am a 5-digit palindrome.

I am an odd number.

My ‘t’ digit is double of my ‘u’ digit.

My ‘h’ digit is double of my ‘t’ digit.

Who am I? _________________

Answer:

Let's solve this puzzle by breaking down the clues one by one.

Clue 1: "I am a 5-digit palindrome."

A 5-digit palindrome is a number that reads the same forwards and backward. This means its structure must be $abcba$. The first digit ('a') is the same as the last, and the second digit ('b') is the same as the fourth.

Clue 2: "I am an odd number."

An odd number is a number that ends in an odd digit (1, 3, 5, 7, or 9). Since the last digit of our palindrome is 'a', this means 'a' must be 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9.

Clue 3: "My ‘t’ digit is double of my ‘u’ digit."

In a 5-digit number, the place values are Ten Thousands, Thousands, Hundreds, Tens, and Units.

The 't' (tens) digit is 'b'.

The 'u' (units) digit is 'a'.

So, this clue tells us that $b = 2 \times a$.

Clue 4: "My ‘h’ digit is double of my ‘t’ digit."

The 'h' (hundreds) digit is 'c'.

The 't' (tens) digit is 'b'.

So, this clue tells us that $c = 2 \times b$.

Putting the clues together to find the digits:

1. We know from Clue 2 that 'a' must be an odd digit: 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9.

2. We also know from Clue 3 that $b = 2 \times a$. Let's test the possible values for 'a':

- If $a = 1$, then $b = 2 \times 1 = 2$.

- If $a = 3$, then $b = 2 \times 3 = 6$.

- If $a = 5$, then $b = 2 \times 5 = 10$. A digit cannot be 10, so this is not possible. Any 'a' larger than 3 will also result in a 'b' that is not a single digit.

So, the only possibilities are (a=1, b=2) or (a=3, b=6).

3. Now let's use Clue 4: $c = 2 \times b$.

- If $b = 2$, then $c = 2 \times 2 = 4$.

- If $b = 6$, then $c = 2 \times 6 = 12$. A digit cannot be 12, so this is not possible.

This leaves us with only one set of possible digits:

$a = 1$

$b = 2$

$c = 4$

Constructing the Number:

The structure of the palindrome is $abcba$. Substituting our values:

$a=1, b=2, c=4, b=2, a=1$

The number is 12421.

Who am I? 12,421

Intext Question (Page 64)

On the usual 12-hour clock, there are timings with different patterns. For example, 4:44, 10:10, 12:21.

Question 1:

Try and find out all possible times on a 12-hour clock of each of these types.

Manish has his birthday on 20/12/2012 where the digits ‘2’, ‘0’, ‘1’, and ‘2’ repeat in that order.

Answer:

We need to find all possible times on a standard 12-hour clock that match three different patterns: H:HH (like 4:44), HH:HH (like 10:10), and AB:BA (like 12:21).

Type 1: Pattern like 4:44 (H:HH)

In this pattern, a single-digit hour (H) is the same as both digits of the minutes (MM). This is only possible if the minute value is 59 or less.

- 1:11 (Valid)

- 2:22 (Valid)

- 3:33 (Valid)

- 4:44 (Valid)

- 5:55 (Valid)

- 6:66 (Invalid, as minutes cannot be 66)

The possible times for this pattern are: 1:11, 2:22, 3:33, 4:44, 5:55.

Type 2: Pattern like 10:10 (HH:HH)

In this pattern, a two-digit hour (HH) is exactly repeated in the minutes (MM). The possible two-digit hours are 10, 11, and 12.

- 10:10 (Valid)

- 11:11 (Valid)

- 12:12 (Valid)

The possible times for this pattern are: 10:10, 11:11, 12:12.

Type 3: Pattern like 12:21 (AB:BA)

In this pattern, the digits of a two-digit hour (AB) are reversed for the minutes (BA). The possible hours are 10, 11, and 12.

- Hour 10: Reverse is 01. Time is 10:01. (Valid)

- Hour 11: Reverse is 11. Time is 11:11. (Valid)

- Hour 12: Reverse is 21. Time is 12:21. (Valid)

The possible times for this pattern are: 10:01, 11:11, 12:21.

Question 2: Find some other dates of this form from the past.

Answer:

The pattern from Manish's birthday (20/12/2012) is that the year is formed by writing the digits of the day followed by the digits of the month (DD/MM/DDMM). We need to find other valid dates from the past (before the current year) that follow this rule.

Examples of such dates from the past:

To find these, we can pick any valid day (DD) and month (MM) and form the year (DDMM).

- 01/01/0101 (January 1st, 101)

- 05/06/0506 (June 5th, 506)

- 10/10/1010 (October 10th, 1010)

- 11/11/1111 (November 11th, 1111)

- 12/12/1212 (December 12th, 1212)

- 15/04/1504 (April 15th, 1504)

- 19/08/1908 (August 19th, 1908)

- 20/01/2001 (January 20th, 2001)

- 20/12/2012 (December 20th, 2012 - the example date)

Question 3: Find all possible dates of this form from the past.

Answer:

We are looking for all valid dates in the format DD/MM/YYYY where the year is formed by the digits of the day and month (YYYY = DDMM).

Finding the Range:

Let the current year be 2024 for this example. The year formed, DDMM, must be less than 2024. The largest possible month is 12. If the day is 20, the year is 2012. If the day were 21, the earliest year would be 2101, which is in the future. Therefore, the day (DD) can only be from 01 to 20.

Since the maximum day we can use is 20, we don't need to worry about invalid dates like the 31st of April, because days like 21, 22, etc., are already excluded.

Listing All Possible Dates:

We can have any day from 01 to 20, and for each of those days, we can have any month from 01 to 12.

- For DD = 01, there are 12 dates (from 01/01/0101 to 01/12/0112).

- For DD = 02, there are 12 dates (from 02/01/0201 to 02/12/0212).

- ...and so on...

- For DD = 20, there are 12 dates (from 20/01/2001 to 20/12/2012).

Total Number of Dates:

Since there are 20 possible values for the day (01 to 20) and 12 possible values for the month for each day, the total number of such dates is:

Total Dates = $20 \times 12 = 240$.

There are 240 such dates in the past that follow this pattern.

Question 4: But, will any year’s calendar repeat again after some years? Will all dates and days in a year match exactly with that of another year?

Answer:

Yes, a year's calendar will repeat itself exactly. This means that January 1st will fall on the same day of the week, and the pattern of days will match for the entire year.

Conditions for a Calendar to Repeat:

For a calendar to repeat, two things must be true:

1. The year must start on the same day of the week.

2. Both years must be the same type (either both normal years with 365 days or both leap years with 366 days).

How it Works:

- A normal year (365 days) is 52 weeks and 1 extra day. This causes the start day of the next year to shift forward by 1 day.

- A leap year (366 days) is 52 weeks and 2 extra days. This causes the start day of the next year to shift forward by 2 days.

A calendar repeats when the total number of "shifted" days adds up to a multiple of 7 (like 7, 14, 21, etc.).

Common Repetition Cycles:

Because of this, calendars often repeat in cycles of 6, 11, or 28 years.

- Example of a 6-year repeat: The calendar for 2015 repeated in 2021.

- Example of an 11-year repeat: The calendar for 2014 will repeat in 2025.

- Example of a 28-year repeat: The calendar for a leap year like 1996 will repeat 28 years later, in 2024.

So, you can often reuse an old calendar if you wait for the right year!

Figure it Out (Page 64 - 65)

Question 1. Pratibha uses the digits ‘4’, ‘7’, ‘3’ and ‘2’, and makes the smallest and largest 4-digit numbers with them: 2347 and 7432. The difference between these two numbers is 7432 – 2347 = 5085. The sum of these two numbers is 9779. Choose 4–digits to make:

a. the difference between the largest and smallest numbers greater than 5085.

b. the difference between the largest and smallest numbers less than 5085.

c. the sum of the largest and smallest numbers greater than 9779.

d. the sum of the largest and smallest numbers less than 9779.

Answer:

We need to choose a set of four different digits for each condition. For any set of digits {a, b, c, d} arranged from smallest to largest, the smallest number will be 'abcd' and the largest will be 'dcba'.

a. Difference greater than 5085

To get a large difference, we need the first digit of the largest number to be big, and the first digit of the smallest number to be small. This means we need a wide spread between the smallest and largest digits. Let's choose the digits {1, 2, 8, 9}.

Largest number (L): 9821

Smallest number (S): 1289

Difference = $9821 - 1289 = 8532$. Since $8532 > 5085$, this works.

b. Difference less than 5085

To get a small difference, we need the digits to be close together. Let's choose consecutive digits like {3, 4, 5, 6}.

Largest number (L): 6543

Smallest number (S): 3456

Difference = $6543 - 3456 = 3087$. Since $3087 < 5085$, this works.

c. Sum greater than 9779

To get a large sum, the digits we choose should be large. Let's choose {5, 6, 8, 9}.

Largest number (L): 9865

Smallest number (S): 5689

Sum = $9865 + 5689 = 15554$. Since $15554 > 9779$, this works.

d. Sum less than 9779

To get a small sum, the digits we choose should be small. Let's choose {1, 2, 3, 4}.

Largest number (L): 4321

Smallest number (S): 1234

Sum = $4321 + 1234 = 5555$. Since $5555 < 9779$, this works.

Question 2. What is the sum of the smallest and largest 5-digit palindrome? What is their difference?

Answer:

First, we need to find the smallest and the largest 5-digit palindromes.

A 5-digit palindrome has the form ABCBA, where A cannot be 0.

Smallest 5-digit palindrome:

To make the number as small as possible, we must choose the smallest possible digits from left to right.

The first digit (A) must be the smallest non-zero digit, which is 1.

The next digits (B and C) should be the smallest digit possible, which is 0.

So, the number is 10001.

The smallest 5-digit palindrome is 10,001.

Largest 5-digit palindrome:

To make the number as large as possible, we must choose the largest possible digits from left to right.

The digits A, B, and C should all be the largest possible digit, which is 9.

So, the number is 99999.

The largest 5-digit palindrome is 99,999.

Sum of the smallest and largest:

Sum = $10,001 + 99,999 = \textbf{110,000}$

$\begin{array}{cc} & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ + & 9 & 9 & 9 & 9 & 9 \\ \hline 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ \hline \end{array}$

Difference between the largest and smallest:

Difference = $99,999 - 10,001 = \textbf{89,998}$

$\begin{array}{cc} & 9 & 9 & 9 & 9 & 9 \\ - & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \hline & 8 & 9 & 9 & 9 & 8 \\ \hline \end{array}$

Question 3. The time now is 10:01. How many minutes until the clock shows the next palindromic time? What about the one after that?

Answer:

A palindromic time reads the same forwards and backward (e.g., 1:01, 12:21). The current time is 10:01.

Finding the Next Palindromic Times:

We need to find the palindromic times that come after 10:01.

- In the 10 o'clock hour, the only palindrome is 10:01 itself.

- In the 11 o'clock hour, the only palindrome is 11:11. This is the next one.

- In the 12 o'clock hour, the only palindrome is 12:21. This is the one after that.

Calculating the Time Differences:

1. Minutes until the next palindromic time (11:11):

To get from 10:01 to 11:11, we can count:

From 10:01 to 11:01 is exactly 1 hour, which is 60 minutes.

From 11:01 to 11:11 is another 10 minutes.

Total minutes = $60 + 10 = 70$ minutes.

It is 70 minutes until the next palindromic time.

2. Minutes until the palindromic time after that (12:21):

To get from 11:11 to 12:21, we can count:

From 11:11 to 12:11 is exactly 1 hour, which is 60 minutes.

From 12:11 to 12:21 is another 10 minutes.

Total minutes from 11:11 to 12:21 = $60 + 10 = 70$ minutes.

The time from the start (10:01) is $70 \text{ (to 11:11)} + 70 \text{ (to 12:21)} = 140$ minutes.

The time until the one after that is 140 minutes from 10:01.

Question 4. How many rounds does the number 5683 take to reach the Kaprekar constant?

Answer:

To solve this, we apply Kaprekar's routine (arrange digits to make the largest and smallest numbers, then subtract) repeatedly until we reach 6174.

Starting number: 5683

Round 1:

Digits: {3, 5, 6, 8}. Largest: 8653. Smallest: 3568.

Difference = $8653 - 3568 = 5085$

Round 2:

Number: 5085. Digits: {0, 5, 5, 8}. Largest: 8550. Smallest: 0558.

Difference = $8550 - 558 = 7992$

Round 3:

Number: 7992. Digits: {2, 7, 9, 9}. Largest: 9972. Smallest: 2799.

Difference = $9972 - 2799 = 7173$

Round 4:

Number: 7173. Digits: {1, 3, 7, 7}. Largest: 7731. Smallest: 1377.

Difference = $7731 - 1377 = 6354$

Round 5:

Number: 6354. Digits: {3, 4, 5, 6}. Largest: 6543. Smallest: 3456.

Difference = $6543 - 3456 = 3087$

Round 6:

Number: 3087. Digits: {0, 3, 7, 8}. Largest: 8730. Smallest: 0378.

Difference = $8730 - 378 = 8352$

Round 7:

Number: 8352. Digits: {2, 3, 5, 8}. Largest: 8532. Smallest: 2358.

Difference = $8532 - 2358 = 6174$

We have reached Kaprekar's constant, 6174. The process stops here.

It took 7 rounds for the number 5683 to reach the constant.

Intext Question (Page 66)

(1500 + 1500 + 400 = 3400)

The numbers in the middle can be used as many times as needed to get the desired sum.Draw arrows from the middle to the numbers on the sides to obtain the desired sums.

Two examples are given. It is simpler to do it mentally!

38,800 = 25,000 + 400 × 2 + 13,000

3400 = 1500 + 1500 + 400

Question: Can we make 1,000 using the numbers in the middle? Why not? What about 14,000, 15,000 and 16,000? Yes, it is possible. Explore how. What thousands cannot be made?

Answer:

This is a puzzle about forming different sums using a given set of numbers. The numbers available in the middle column are: 25,000, 400, 13,000, 1,500, and 60,000. We can use any of these numbers as many times as we need.

Can we make 1,000 using the numbers in the middle? Why not?

No, it is not possible to make exactly 1,000.

Reasoning:

To make a sum as small as 1,000, we can only use the numbers from the middle column that are smaller than or equal to 1,000. The only number that fits this condition is 400.

Therefore, we can only try to make 1,000 by adding 400 to itself multiple times.

- $400 \times 1 = 400$ (Too small)

- $400 \times 2 = 800$ (Too small)

- $400 \times 3 = 1,200$ (Too large)

Since 1,000 is not a multiple of 400, we can never reach it exactly. Thus, we cannot make 1,000.

What about 14,000, 15,000 and 16,000? Yes, it is possible. Explore how.

Yes, all of these can be made. Here is one way to form each sum:

To make 14,000:

We can use the number 400 repeatedly.

$14,000 \div 400 = 35$

So, $14,000 = 35 \times 400$.

(Another way: $8 \times 1,500 + 5 \times 400 = 12,000 + 2,000 = 14,000$)

To make 15,000:

We can start with 13,000 and add 2,000 more. We can make 2,000 by using 400 five times ($5 \times 400 = 2,000$).

So, $15,000 = 13,000 + (5 \times 400)$.

(Another way: $10 \times 1,500 = 15,000$)

To make 16,000:

We can start with 13,000 and add 3,000 more. We can make 3,000 by using 1,500 two times ($2 \times 1,500 = 3,000$).

So, $16,000 = 13,000 + (2 \times 1,500)$.

What thousands cannot be made?

As we discovered earlier, 1,000 cannot be made. Let's think about why and if there are others.

Any sum we make must be a combination of the available numbers. The two smallest numbers are 400 and 1,500. The greatest common divisor of all the numbers in the middle column is 100, which means any sum we create must be a multiple of 100.

While most large multiples of 1,000 can be made, some smaller ones are impossible. Based on the available numbers, we cannot form sums like 100, 200, 300, 500, etc. The smallest possible sum is 400.

When looking specifically for "thousands" (multiples of 1,000), we find that 1,000 is impossible. It turns out that other small "thousands" like 2,000 ($5 \times 400$) and 3,000 ($2 \times 1,500$) are possible. After exploring the combinations, 1,000 appears to be the only multiple of 1,000 that cannot be formed.

Figure it Out (Page 66 - 67)

Could you find examples for all the cases? If not, think and discuss what could be the reason. Make other such questions and challenge your classmates.

Answer:

Here are examples for each scenario described on the cards. For each one, we will provide a sample calculation that meets the given conditions.

Top Row (Addition)

1. 5-digit + 5-digit to give a 5-digit sum more than 90,250

Example: $50,000 + 45,000 = 95,000$ (which is > 90,250)

2. 5-digit + 3-digit to give a 6-digit sum

To get a 6-digit sum (i.e., 100,000 or more), the 5-digit number must be very large.

Example: $99,500 + 500 = 100,000$

3. 4-digit + 4-digit to give a 6-digit sum

This is not possible.

Reason: The largest possible 4-digit number is 9,999. If we add the two largest 4-digit numbers:

$9,999 + 9,999 = 19,998$

The result is 19,998, which is a 5-digit number. It is impossible to get a 6-digit sum by adding two 4-digit numbers.

4. 5-digit + 5-digit to give a 6-digit sum

Example: $50,000 + 50,000 = 100,000$

5. 5-digit + 5-digit to give 18,500

This is not possible.

Reason: The smallest 5-digit number is 10,000. If we add the two smallest 5-digit numbers:

$10,000 + 10,000 = 20,000$

The smallest possible sum is 20,000, which is already greater than 18,500. It is impossible to get a sum of 18,500 by adding two 5-digit numbers.

Bottom Row (Subtraction)

1. 5-digit – 5-digit to give a difference less than 56,503

Example: $70,000 - 20,000 = 50,000$ (which is < 56,503)

2. 5-digit – 3-digit to give a 4-digit difference

Example: $10,500 - 600 = 9,900$

3. 5-digit – 4-digit to give a 4-digit difference

Example: $12,000 - 3,000 = 9,000$

4. 5-digit – 5-digit to give a 3-digit difference

To get a small difference, the two numbers should be close in value.

Example: $10,500 - 10,000 = 500$

5. 5-digit – 5-digit to give 91,500

This is not possible.

Reason: To get a large difference, we need to subtract a small number from a large number. Let's use the largest possible 5-digit number and the smallest possible 5-digit number:

Largest 5-digit number: 99,999

Smallest 5-digit number: 10,000

The maximum possible difference is: $99,999 - 10,000 = 89,999$.

Since the largest possible difference is 89,999, it is impossible to get a difference of 91,500.

Question 2. Always, Sometimes, Never?

Below are some statements. Think, explore and find out if each of the statement is ‘Always true’, ‘Only sometimes true’ or ‘Never true’. Why do you think so? Write your reasoning; discuss this with the class.

a. 5-digit number + 5-digit number gives a 5-digit number

b. 4-digit number + 2-digit number gives a 4-digit number

c. 4-digit number + 2-digit number gives a 6-digit number

d. 5-digit number – 5-digit number gives a 5-digit number

e. 5-digit number – 2-digit number gives a 3-digit number

Answer:

Here is an analysis of each statement to determine if it is always true, sometimes true, or never true, along with the reasoning.

a. 5-digit number + 5-digit number gives a 5-digit number

This statement is Sometimes True.

Reasoning:

- Example where it is true (gives a 5-digit number):

$20,000 + 30,000 = 50,000$ (The sum is a 5-digit number). - Example where it is false (gives a 6-digit number):

$70,000 + 80,000 = 150,000$ (The sum is a 6-digit number).

The result depends on the specific numbers being added. If the sum is less than 100,000, the result is a 5-digit number. If the sum is 100,000 or more, it becomes a 6-digit number.

b. 4-digit number + 2-digit number gives a 4-digit number

This statement is Sometimes True.

Reasoning:

- Example where it is true (gives a 4-digit number):

$5,000 + 50 = 5,050$ (The sum is a 4-digit number). - Example where it is false (gives a 5-digit number):

This happens when the 4-digit number is very close to 10,000. For example:

$9,950 + 50 = 10,000$ (The sum is a 5-digit number).

Most of the time the sum will be a 4-digit number, but if the addition causes a carry-over past 9,999, the result becomes a 5-digit number.

c. 4-digit number + 2-digit number gives a 6-digit number

This statement is Never True.

Reasoning:

To get the largest possible sum, we must add the largest 4-digit number and the largest 2-digit number.

Largest 4-digit number = 9,999

Largest 2-digit number = 99

Maximum possible sum = $9,999 + 99 = 10,098$.

The result is 10,098, which is a 5-digit number. Since the maximum possible sum is only a 5-digit number, it is impossible to get a 6-digit sum.

d. 5-digit number – 5-digit number gives a 5-digit number

This statement is Sometimes True.

Reasoning:

- Example where it is true (gives a 5-digit number):

$80,000 - 20,000 = 60,000$ (The difference is a 5-digit number). - Example where it is false (gives a 4-digit number or smaller):

This happens when the two numbers are close in value.

$15,000 - 12,000 = 3,000$ (The difference is a 4-digit number).

The number of digits in the result depends on how far apart the two numbers are.

e. 5-digit number – 2-digit number gives a 3-digit number

This statement is Never True.

Reasoning:

To get the smallest possible difference, we must subtract the largest possible 2-digit number from the smallest possible 5-digit number.

Smallest 5-digit number = 10,000

Largest 2-digit number = 99

Minimum possible difference = $10,000 - 99 = 9,901$.

The result is 9,901, which is a 4-digit number. Since the smallest possible difference is already a 4-digit number, it is impossible to get a 3-digit difference.

Intext Question (Page 67 - 68)

Share and discuss in class the different methods each of you used to solve these questions.

Answer:

For each of these figures, we can find the sum much faster by using multiplication instead of adding the numbers one by one. The key is to group identical numbers together.

Figure a:

We see two groups of numbers: 40s and 50s.

- Count the number of 40s: There are 12 boxes with the number 40.

- Count the number of 50s: There are 10 boxes with the number 50.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Total = (Number of 40s $\times$ 40) + (Number of 50s $\times$ 50)

Total = $(12 \times 40) + (10 \times 50)$

Total = $480 + 500 = 980$

Sum = 980

Figure b:

The figure shows an 8x8 grid of 64 boxes. The boxes contain either 1 dot or 5 dots.

- Count the squares with 5 dots: There are 20 such squares.

- Count the squares with 1 dot: Since there are 64 squares in total, the number of squares with 1 dot is $64 - 20 = 44$.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Total = (Number of 5-dot squares $\times$ 5) + (Number of 1-dot squares $\times$ 1)

Total = $(20 \times 5) + (44 \times 1)$

Total = $100 + 44 = 144$

Sum = 144

Figure c:

We see two groups of numbers: 32s and 64s.

- Count the number of 32s: There are 4 rows of 8, so $4 \times 8 = 32$ boxes.

- Count the number of 64s: There are 4 rows of 3 on the left and 4 on the right, so $(4 \times 3) + 4 = 12 + 4 = 16$ boxes.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Total = (Number of 32s $\times$ 32) + (Number of 64s $\times$ 64)

Total = $(32 \times 32) + (16 \times 64)$

Total = $1024 + 1024 = 2048$

Sum = 2048

Figure d:

The figure is made of 28 boxes containing either 3 or 4 dots.

- Count the boxes with 4 dots: There are 18 boxes.

- Count the boxes with 3 dots: The remaining boxes must have 3 dots. Number of 3-dot boxes = $28 - 18 = 10$.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Total = (Number of 4-dot boxes $\times$ 4) + (Number of 3-dot boxes $\times$ 3)

Total = $(18 \times 4) + (10 \times 3)$

Total = $72 + 30 = 102$

Sum = 102

Figure e:

To find the sum, let's count the total number of times each value (15, 25, 35) appears, based on your detailed breakdown of the shapes.

- Total count of 35s: (2 hexagons $\times$ 6) + (1 hexagon $\times$ 2) + (2 quadrilaterals $\times$ 4) = $12 + 2 + 8 = 22$.

- Total count of 25s: (2 hexagons $\times$ 6) + (1 hexagon $\times$ 2) + (2 quadrilaterals $\times$ 4) = $12 + 2 + 8 = 22$.

- Total count of 15s: (2 hexagons $\times$ 6) + (1 hexagon $\times$ 2) + (2 quadrilaterals $\times$ 4) = $12 + 2 + 8 = 22$.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Since each number appears 22 times, we can use the distributive property:

Total = $(22 \times 35) + (22 \times 25) + (22 \times 15)$

Total = $22 \times (35 + 25 + 15)$

Total = $22 \times 75 = 1650$

Sum = 1650

Figure f:

The circular target has four groups of numbers.

- Outer Ring: 18 numbers of 125.

- Second Ring: 8 numbers of 250.

- Third Ring: 4 numbers of 500.

- Center: 1 number of 1000.

Quicker Way (Calculation):

Total = $(18 \times 125) + (8 \times 250) + (4 \times 500) + (1 \times 1000)$

Total = $2250 + 2000 + 2000 + 1000 = 7250$

Sum = 7250

Intext Question (Page 69)

Question:

Make some more Collatz sequences like those above, starting with your favourite whole numbers. Do you always reach 1?

Do you believe the conjecture of Collatz that all such sequences

will eventually reach 1? Why or why not?

Answer:

This question is about the famous Collatz Conjecture, a puzzle that mathematicians have been trying to solve for many years! Let's explore it with some of our own examples.

The rules for the sequence are simple:

- If your number is even, you divide it by 2 ($n \div 2$).

- If your number is odd, you multiply it by 3 and add 1 ($3n + 1$).

You then repeat this process with the new number you get.

Let's Make Some Collatz Sequences

Example 1: Starting with my favourite number, 7.

7 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 7) + 1 = 22$

22 is even $\rightarrow 22 \div 2 = 11$

11 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 11) + 1 = 34$

34 is even $\rightarrow 34 \div 2 = 17$

17 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 17) + 1 = 52$

52 is even $\rightarrow 52 \div 2 = 26$

26 is even $\rightarrow 26 \div 2 = 13$

13 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 13) + 1 = 40$

40 is even $\rightarrow 40 \div 2 = 20$

20 is even $\rightarrow 20 \div 2 = 10$

10 is even $\rightarrow 10 \div 2 = 5$

5 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 5) + 1 = 16$

16 is even $\rightarrow 16 \div 2 = 8$

8 is even $\rightarrow 8 \div 2 = 4$

4 is even $\rightarrow 4 \div 2 = 2$

2 is even $\rightarrow 2 \div 2 = 1$

Once we reach 1, the sequence gets stuck in a small loop: $1 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1$. So, we stop at 1.

Example 2: Starting with the number 12.

12 is even $\rightarrow 12 \div 2 = 6$

6 is even $\rightarrow 6 \div 2 = 3$

3 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 3) + 1 = 10$

10 is even $\rightarrow 10 \div 2 = 5$

5 is odd $\rightarrow (3 \times 5) + 1 = 16$

From 16, we know the sequence continues down to 1.

Do you always reach 1?

Based on our examples and countless others that people have tried, it seems that yes, we always reach 1. Every single whole number that has ever been tested, no matter how large, has eventually fallen into the $4 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1$ loop.

Do you believe the conjecture of Collatz that all such sequences will eventually reach 1? Why or why not?

This is a fantastic question, and it's the reason why this puzzle is so famous!

Why I believe it is likely true:

Mathematicians have used powerful computers to test this conjecture for an incredible number of starting values. They have checked every number up to quintillions (that's a 1 followed by 18 zeros!), and every single one has eventually come down to 1. With so much evidence and no counterexamples found, it's very easy to believe that the conjecture is true.

Why it is still an unsolved puzzle (the "why not"):

In mathematics, checking a lot of examples is not the same as a proof. A proof has to show that the rule works for all whole numbers, including ones so gigantic that no computer could ever test them. Just because we haven't found a number that fails doesn't mean one doesn't exist. There are two possibilities that nobody has been able to rule out with a proof:

- Maybe there is a starting number that gets stuck in a different loop that doesn't include 1.

- Maybe there is a starting number whose sequence just keeps growing bigger and bigger forever and never comes down.

So, while I personally believe the conjecture is true based on the overwhelming evidence, it remains one of the most famous unsolved problems in mathematics because no one has been able to write a logical proof that guarantees it works for every number.

Figure it Out (Page 69 - 70)

Question: We shall do some simple estimates. It is a fun exercise, and you may find it amusing to know the various numbers around us. Remember, we are not interested in the exact numbers for the following questions. Share your methods of estimation with the class.

1. Steps you would take to walk:

a. From the place you are sitting to the classroom door

b. Across the school ground from start to end

c. From your classroom door to the school gate

d. From your school to your home

2. Number of times you blink your eyes or number of breaths you take:

a. In a minute

b. In an hour

c. In a day

3. Name some objects around you that are:

a. few thousand in number

b. more than ten thousand in number

Answer:

This is a fun exercise in estimation! Remember, the goal is not to find the exact answer but to think of clever ways to get a good guess. Here are some methods and examples.

1. Steps you would take to walk:

a. From the place you are sitting to the classroom door

Method: For such a short distance, the best way to estimate is to simply stand up and count your steps as you walk to the door.

Estimate: This would probably be around 5 to 15 steps.

b. Across the school ground from start to end

Method: You could walk the distance once and count your steps. A quicker way is to estimate the distance in a known unit, like meters. A cricket pitch is about 20 meters long. You could guess how many "cricket pitches" would fit across the ground and then multiply. Let's say one step is about half a meter.

Estimate: If a school ground is about 100 meters long, and one big step is about half a meter, the estimate would be around 200 steps.

c. From your classroom door to the school gate

Method: This is likely a longer walk. You can count the steps one day on your way out. Or, you could estimate the number of classrooms you pass and guess the steps for each section.

Estimate: This could be anywhere from 100 to 500 steps, depending on the size of your school.

d. From your school to your home

Method: This is too long to count directly. A good way to estimate is to first find out the distance in kilometers. Let's say your home is 2 kilometers away from school. A person your age takes about 1,500 steps to walk one kilometer.

Calculation: $2 \text{ kilometers} \times 1,500 \text{ steps/kilometer} = 3,000 \text{ steps}$.

Estimate: If you live 2 km away, it would be around 3,000 steps.

2. Number of times you blink your eyes or number of breaths you take:

a. In a minute

Method: You can't easily count for a full minute without getting distracted. A better way is to count for a shorter time, like 15 seconds, and then multiply by 4 (since $15 \times 4 = 60$ seconds, or 1 minute).

Estimate: A person blinks about 15 to 20 times a minute. Let's use 20 blinks per minute for our calculation.

b. In an hour

Method: Take your estimate for one minute and multiply it by 60 (since there are 60 minutes in an hour).

Calculation: $20 \text{ blinks/minute} \times 60 \text{ minutes} = 1,200 \text{ blinks}$.

Estimate: About 1,200 blinks in an hour.

c. In a day

Method: Take your estimate for one hour and multiply it by 24. However, we should be clever: we don't blink when we are asleep! Let's say you are awake for 16 hours and sleep for 8 hours.

Calculation:

Blinks while awake: $1,200 \text{ blinks/hour} \times 16 \text{ hours} = 19,200 \text{ blinks}$.

Blinks while asleep: 0.

Estimate: Around 19,200 blinks in a day.

3. Name some objects around you that are:

a. few thousand in number

- The number of books in the school library. (A small library might have 2,000 to 5,000 books).

- The number of tiles on the floor of the entire school building.

- The number of students in a very large school or a small college.

- The number of words on a few pages of a newspaper.

b. more than ten thousand in number