| Latest Maths NCERT Books Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

| Content On This Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Figure it Out (Page 219) | Figure it Out (Page 223 - 230) | Figure it Out (Page 235 - 236) |

| Figure it Out (Page 238) | ||

Chapter 9 Symmetry

Welcome to the solutions guide for Chapter 9, "Symmetry," a fascinating exploration within the Class 6 Ganita Prakash mathematics textbook, published by NCERT for the 2024-25 academic session. This chapter invites students into the visually appealing world of balance, harmony, and geometric regularity. Symmetry is a fundamental concept found not only in mathematics but also extensively in nature, art, architecture, and design. These solutions are meticulously prepared to help students grasp the core ideas of symmetry, primarily focusing on reflectional symmetry, more commonly known as line symmetry, and to provide clear, step-by-step methods for solving the exercises presented.

The central theme of this chapter revolves around understanding what makes a shape symmetrical. The solutions provide detailed explanations and numerous illustrations focusing on line symmetry. A figure possesses line symmetry if it can be divided by a line – the line of symmetry or axis of symmetry – into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. Imagine folding the figure along this line; the two parts would perfectly coincide, overlapping exactly. The solutions demonstrate how to identify these crucial lines in a variety of contexts. Students will find clear answers showing the lines of symmetry for:

- Geometric Shapes: Including triangles (distinguishing between an equilateral triangle with 3 lines of symmetry, an isosceles triangle with 1 line, and a scalene triangle with 0 lines), various quadrilaterals (like a square with 4 lines, a rectangle with 2 lines, a rhombus with 2 lines, but a general parallelogram with none), and the special case of a circle, which possesses an infinite number of lines of symmetry passing through its center.

- Letters of the English Alphabet: Examining letters like 'H' (2 lines), 'A' (1 vertical line), 'B' (1 horizontal line), 'O' (multiple/infinite lines ideally, often treated as 2), versus letters like 'F', 'G', or 'P' which have no lines of symmetry.

A key practical skill developed in this chapter, and thoroughly addressed in the solutions, is the ability to complete a figure when given only half of it along with the line of symmetry. The solutions provide detailed instructions and visual guides demonstrating how to accurately reflect the given portion across the line of symmetry to construct the whole, symmetrical shape. This reinforces the mirror-image concept fundamental to reflectional symmetry. While the primary focus remains on line symmetry, some solutions might briefly touch upon the related concept of rotational symmetry. This involves identifying if a shape can be rotated around a central point (the center of rotation) by less than a full $360^\circ$ turn and still look exactly the same. The number of times it matches itself during one full rotation defines its order of rotational symmetry (e.g., a square has rotational symmetry of order 4).

By engaging with these carefully constructed solutions for Chapter 9 of the Class 6 Ganita Prakash (NCERT 2024-25), students are expected to significantly enhance their visual perception and spatial reasoning skills. They learn to recognize and appreciate symmetrical patterns, understand the precise geometric definition of line symmetry, and apply this understanding methodically to analyze both familiar shapes and abstract figures. This chapter builds an intuitive yet formal understanding of a concept that resonates throughout geometry and beyond.

Figure it Out (Page 219)

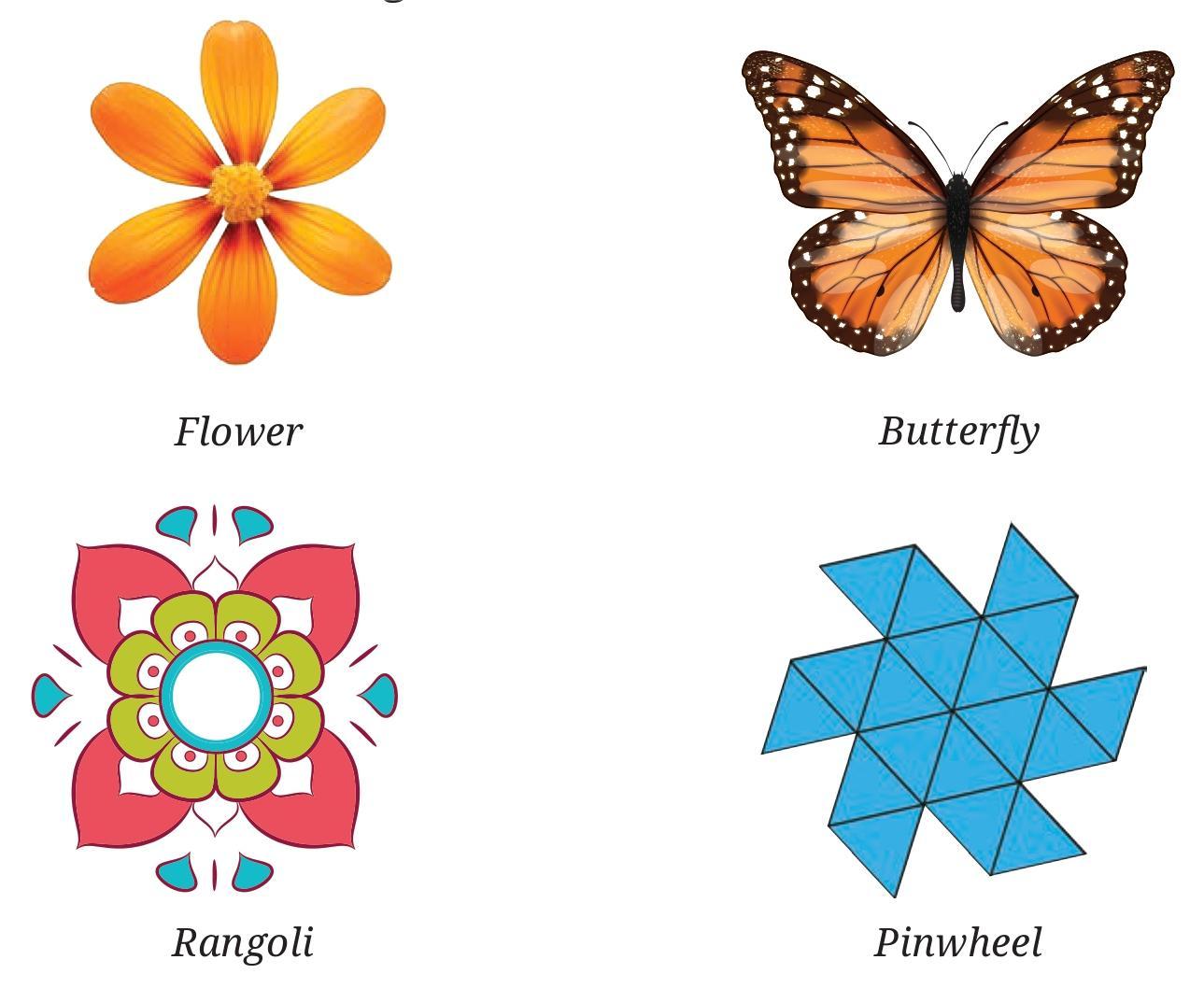

Question 1. Do you see any line of symmetry in the figures at the start of the chapter? What about in the picture of the cloud?

Answer:

A line of symmetry is a line that divides a figure or an object into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. If we fold the figure along the line of symmetry, one half will perfectly overlap the other half.

Let's examine the given figures for lines of symmetry.

Analysis of the figures in the image:

- Flower: Yes, the flower has multiple lines of symmetry. Since it has 6 identical petals arranged symmetrically around the center, it has 6 lines of symmetry.

- Butterfly: Yes, the butterfly has one line of symmetry. It is a vertical line that passes through the center of its body, making the left and right sides mirror images of each other. It has 1 line of symmetry.

- Rangoli: Yes, the rangoli design is symmetrical. It has a vertical line of symmetry, a horizontal line of symmetry, and two diagonal lines of symmetry. In total, it has 4 lines of symmetry.

- Pinwheel: No, the pinwheel does not have any line of symmetry. If you try to fold it along any line, the two halves will not match.

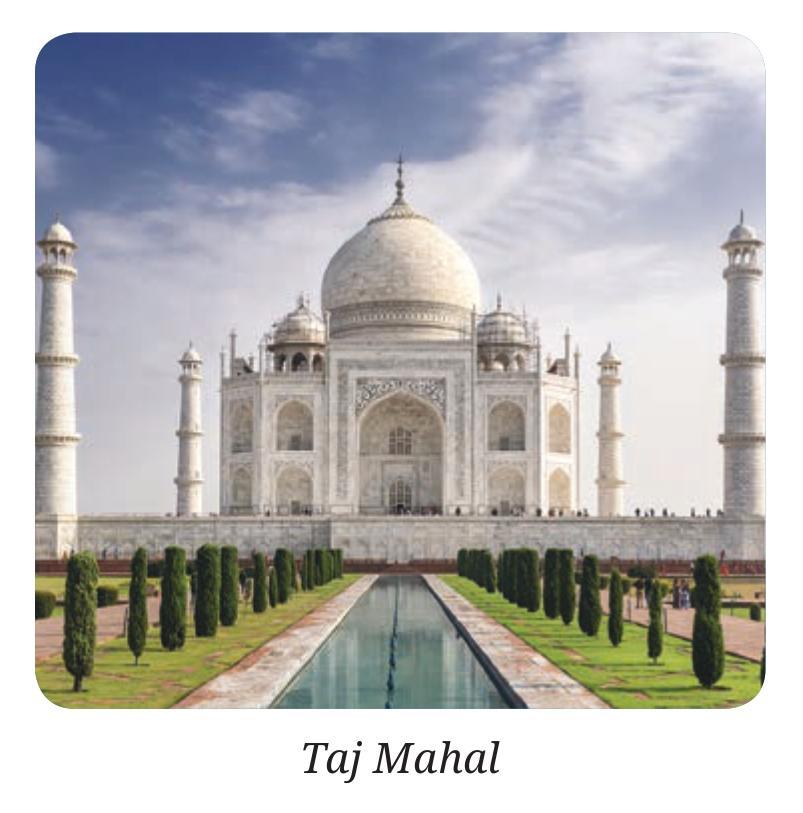

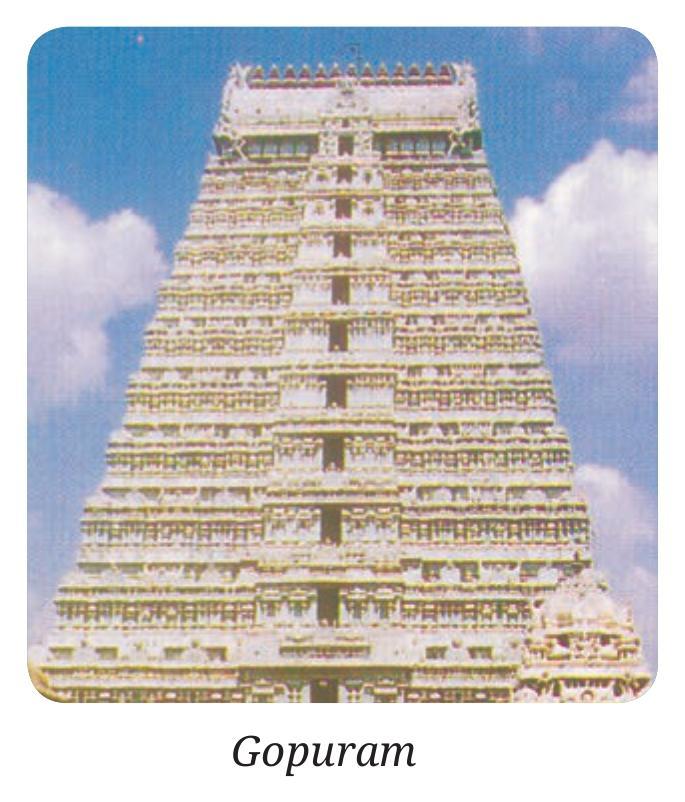

Yes, some of the figures like the Taj Mahal and the Gopuram have one or more lines of symmetry. These structures are designed in such a way that if we fold them along the central vertical line, the two halves will look identical.

However, the cloud shown in the picture does not have any line of symmetry. Its shape is irregular, so it cannot be divided into two equal halves that are mirror images of each other.

Answer:

A line of symmetry is an imaginary line that divides a figure into two identical halves, where each half is a mirror image of the other. We can find the lines of symmetry for each figure by checking if such a line exists.

Let's analyze each figure from left to right:

Figure (a): This figure has one line of symmetry. It is a horizontal line that passes through the middle of the shape.

Figure (b): This figure has one line of symmetry. It is a vertical line that divides the shape into two identical left and right parts.

Figure (c): This quadrilateral has no line of symmetry as all its sides and angles appear to be unequal.

Figure (d): This L-shaped figure has one line of symmetry. It is a diagonal line drawn at the corner of the L-shaped figure.

Figure (e): This triangle has no line of symmetry as all its sides and angles appear to be unequal.

Figure it Out (Page 223 - 230)

Figure (d) was created by punching a single hole. How was the paper folded?

Answer:

The problem asks us to determine the line of fold for a square sheet of paper, given the pattern of holes that appear after punching the folded paper and then unfolding it. The key principle is that the pattern of holes will be symmetrical about the line of fold.

Solution for Figure (a)

To Find: The line of fold for the pattern in Figure (a).

Observation and Reasoning:

In Figure (a), there are two holes. These holes are mirror images of each other across the vertical centre line of the square. If we imagine a vertical line drawn down the middle of the square, the hole on the left is at the same distance from this line as the hole on the right.

This symmetry implies that the paper was folded along this vertical line. A single hole was punched through the two layers of the folded paper. When unfolded, this single punch resulted in two symmetrical holes.

Conclusion:

The paper was folded along its vertical line of symmetry.

Solution for Figure (b)

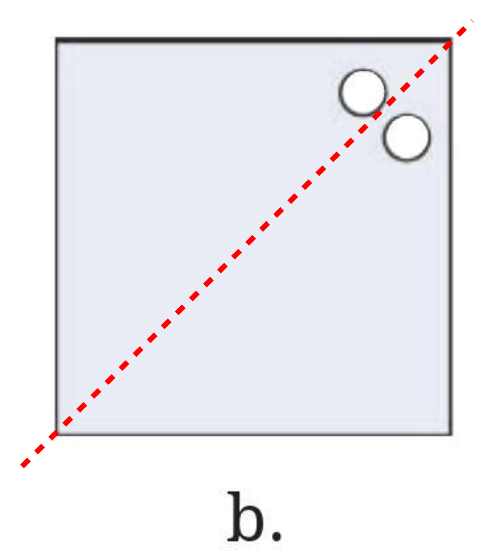

To Find: The line of fold for the pattern in Figure (b).

Observation and Reasoning:

In Figure (b), the two holes are located near the top-right corner. They are positioned symmetrically, as mirror images, across the diagonal line that connects the top-right corner to the bottom-left corner.

This diagonal symmetry indicates that the paper was folded along this specific diagonal. A single hole punched through the resulting triangle would create two symmetrical holes upon unfolding.

Conclusion:

The paper was folded along its diagonal line of symmetry (from the top-right corner to the bottom-left corner).

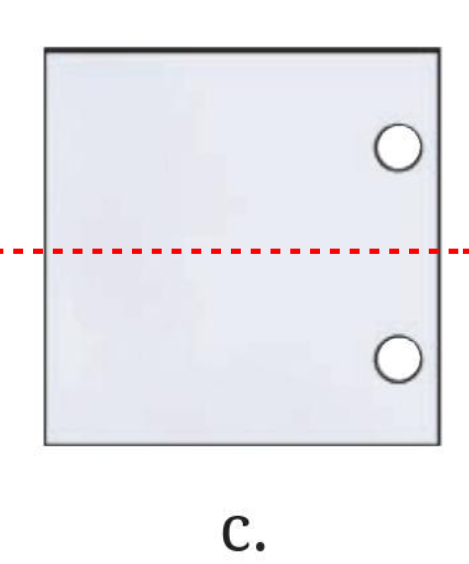

Solution for Figure (c)

To Find: The line of fold for the pattern in Figure (c).

Observation and Reasoning:

In Figure (c), the two holes are mirror images of each other across the horizontal centre line of the square. The top hole is as far from the horizontal centre line as the bottom hole.

This symmetry indicates that the paper was folded along its horizontal middle line. A single punch through the folded paper created two holes when it was unfolded.

Conclusion:

The paper was folded along its horizontal line of symmetry.

Solution for Figure (d)

To Find: How the paper was folded to create the pattern in Figure (d) with a single punch.

Observation and Reasoning:

Figure (d) shows four holes, one at each corner of the square. To create four holes from a single punch, the paper must be folded in such a way that all four corners are stacked on top of each other. This requires folding the paper into four layers, creating a smaller square that is one-fourth the area of the original.

This is achieved by folding the paper twice:

1. First Fold: The paper is folded in half along one of its lines of symmetry (either vertical or horizontal). Let's say it's folded along the vertical line of symmetry.

2. Second Fold: The resulting rectangle is then folded in half again, this time along its line of symmetry (which is the horizontal line of symmetry of the original square).

After these two folds, we have a small square with four layers of paper. All four original corners of the paper are now aligned at one corner of this small folded square. A single hole punched at this stacked corner will pass through all four layers.

When the paper is unfolded, a hole will appear at each of the four original corners.

Conclusion:

The paper was folded into quarters. This was done by first folding it along the vertical line of symmetry and then along the horizontal line of symmetry (or vice versa). A single hole was then punched through the corner where all four original corners of the sheet met.

Answer:

Solution

The task is to find the positions of the other holes based on a given hole and a line of symmetry. The other hole will be the reflection, or mirror image, of the original hole across the given line of symmetry. Each point of the reflected hole will be at the same perpendicular distance from the line of symmetry as the original hole, but on the opposite side.

Solution for Figure (a)

To Find: The position of the other hole in a square with a diagonal line of symmetry from top-left to bottom-right, where the initial hole is below this line near the top-left corner.

Explanation: The line of symmetry is the diagonal that connects the top-left corner to the bottom-right corner. The given hole is below this line. To find the other hole, we reflect the existing hole across this diagonal line. The reflected hole will appear above the line of symmetry, near the bottom-right corner, maintaining the same perpendicular distance from the diagonal line.

Result: The final figure will have two holes placed symmetrically across the diagonal as shown below.

Solution for Figure (b)

To Find: The position of the other hole in a square with a horizontal line of symmetry, where the initial hole is in the bottom-right corner.

Explanation: The figure has a horizontal line of symmetry passing through its center. The given hole is in the bottom-right quadrant. We reflect this hole across the horizontal line. The new hole will appear in the top-right quadrant, directly above the original hole and at the same vertical distance from the line of symmetry.

Result: The final figure will have two holes, one in the bottom-right and one in the top-right, as shown below.

Solution for Figure (c)

To Find: The position of the other hole in an equilateral triangle with a vertical line of symmetry, where the initial hole is on the left side near the top vertex.

Explanation: The line of symmetry is the altitude from the top vertex to the base, which divides the equilateral triangle into two congruent right-angled triangles. The given hole is on the left side of this line. Its reflection will be on the right side, at the same height and at the same horizontal distance from the vertical line of symmetry.

Result: The final figure will have two holes placed symmetrically as shown below.

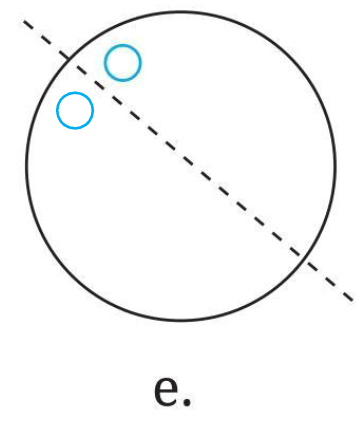

Solution for Figure (d)

To Find: The position of the other hole in a circle with a diameter as the line of symmetry, where the initial hole is above the line near the right circumference.

Explanation: The line of symmetry is a diameter of the circle. The given hole is above this diameter. To find the other hole, we reflect the existing hole across the diameter. The new hole will be located below the diameter, at the same perpendicular distance from it and at the same horizontal position near the right circumference.

Result: The final figure will have two holes, one above and one below the diameter, as shown below.

Solution for Figure (e)

To Find: The position of the other hole in a circle with a diameter as the line of symmetry, where the initial hole is above the line near the left circumference.

Explanation: The line of symmetry is a diameter of the circle, and the initial hole is above this line near the left side. The reflection of this hole across the diameter will be below the diameter, at the same perpendicular distance from it and at the same horizontal position near the left circumference.

Result: The final figure will have two holes, one above and one below the diameter on the left side, as shown below.

Consider a vertical fold. We represent it this way:

Similarly, a horizontal fold is represented as follows:

Answer:

Understanding Paper Folding and Cutting

The problems based on paper folding and cutting are excellent exercises in visualizing symmetry. The key idea is that the fold line acts as a line of symmetry. Any cut or design you make on the folded paper will be reflected or mirrored across this line of symmetry when the paper is unfolded.

The Vertical Fold

As shown in the first figure, a vertical fold is made along the central vertical line of the paper.

This fold creates a vertical line of symmetry.

If you make a cut on the folded paper, the resulting design will be symmetrical on the left and right sides of the unfolded paper. The right side will be a mirror image of the left side.

The Horizontal Fold

As shown in the second figure, a horizontal fold is made along the central horizontal line.

This fold creates a horizontal line of symmetry.

When you cut the folded paper and then open it, the design will be symmetrical on the top and bottom halves. The bottom part will be a mirror image of the top part.

Activity: Try It Yourself!

The best way to master these types of questions is to perform the actions physically. These problems are designed to be solved through hands-on activity.

We encourage you to take a sheet of paper and follow these steps to understand the concept better:

Step 1: Take a rectangular or square sheet of paper.

Step 2: Make a vertical fold down the middle, just like in the first image.

Step 3: With the paper still folded, make a simple cut (for example, a small triangle or a curve on the outer edge).

Step 4: Before unfolding, try to predict what the full shape will look like. Then, unfold the paper and check your prediction.

By doing this activity with both vertical and horizontal folds (and even diagonal folds), you will build a strong intuition for how symmetry works and be able to solve any paper cutting problem by visualizing the outcome.

Answer:

Solution

The following problems involve predicting the final shape of a piece of paper after it has been folded and cut. The key principle is that the fold line acts as a line of symmetry. The cuts made on the folded paper will be mirrored across this line when the paper is unfolded.

Analysis for Figure (a)

Process:

1. Fold: A sheet of paper is folded in half. Based on the orientation, this is a vertical fold.

2. Cut: A jagged, irregular shape is cut along the folded edge with scissors.

Prediction:

When the paper is unfolded, the vertical fold line will act as a line of symmetry. The jagged cut made on the fold will be mirrored on the other side. This will create a single, symmetrical hole in the center of the paper. The shape of the hole will be perfectly symmetrical, with the left half being the mirror image of the right half.

Analysis for Figure (b)

Process:

1. Fold: A sheet of paper is folded in half vertically.

2. Cut: A V-shaped notch is cut from the open edge (the edge opposite the fold).

Prediction:

The vertical fold line serves as the line of symmetry for the final unfolded shape. However, the cut is made on the open edge, not the folded edge. This means the cut goes through both layers of the paper on the side away from the fold. When the paper is unfolded, the V-shaped cut on the top layer will form a notch on one side of the paper (e.g., the right side), and the V-shaped cut on the bottom layer will form an identical, symmetrical notch on the other side (the left side). The resulting shape will be a rectangle or square with symmetrical V-shaped notches taken out of its left and right sides.

Analysis for Figure (c)

Process:

1. First Fold: A square (purple) paper is folded in half vertically.

2. Second Fold: The resulting rectangle is then folded in half horizontally. The paper is now a smaller square, one-quarter of its original size, with four layers.

3. Cut: As indicated by the dotted lines on the quarter-folded paper, two square notches are cut out. One is cut from the middle of the bottom edge (a folded edge), and the other is cut from the middle of the left edge (also a folded edge).

Prediction:

The paper has two lines of symmetry: a vertical one and a horizontal one. Each cut will be reflected across both axes.

- The square cut on the bottom folded edge (which corresponds to the horizontal centerline of the original paper) will be reflected. When unfolded once (horizontally), it creates a rectangular notch. When unfolded again (vertically), it creates two symmetrical rectangular notches on the left and right sides of the final paper.

- Similarly, the square cut on the left folded edge (which corresponds to the vertical centerline) will create two symmetrical rectangular notches on the top and bottom sides of the final paper.

The final result is a single shape with notches in the middle of all four sides, creating a plus-sign or cross shape. This shape is symmetrical about both the horizontal and vertical axes and matches the final shape shown in the image.

Analysis for Figure (d)

Process as per your description:

1. Fold: A rectangular (yellow) paper is folded in half vertically. This creates a folded edge on one side (let's say the left) and an open edge on the other (the right).

2. Cuts: Two separate rectangular cuts are made: one on the left (folded) edge and another on the right (open) edge.

Prediction based on this process:

- The rectangular cut on the folded edge (left) will be mirrored when unfolded. It will open up to create a single, symmetrical rectangular hole in the center of the paper.

- The rectangular cut on the open edge (right) goes through both layers of paper. When unfolded, this will create two identical rectangular notches, one on the far left edge and one on the far right edge of the final paper.

Therefore, this specific set of cuts would result in a final shape that has both a central rectangular hole and two outer rectangular notches. This outcome is different from the 'H' shape shown in the provided image.

Question 5. Suppose you have to get each of these shapes with some folds and a single straight cut. How will you do it?

a. The hole in the centre is a square.

b. The hole in the centre is a square.

Note: For the above two questions, check if the 4-sided figures in the centre satisfy both the properties of a square.

Answer:

Solution

The objective is to create a specific square-shaped hole in the center of a sheet of paper by using a series of folds and then making only a single straight cut. The key is to fold the paper in such a way that the area to be removed (the hole) is represented by a single corner on the folded paper, which can then be cut off in one go.

Solution for Figure (a): Creating a Square Hole

Objective: To create a square hole in the center of the paper, with its sides parallel to the edges of the original paper.

Folding and Cutting Process:

1. First Fold: Take a square sheet of paper and fold it in half along its first diagonal, bringing two opposite corners together. This creates a triangle.

2. Second Fold: Now, fold this triangle in half again along its line of symmetry, which is the second diagonal of the original square. This brings the other two opposite corners together.

3. Result of Folding: After these two folds, you will have a smaller right-angled triangle with four layers of paper. The corner of this triangle where the two folded edges meet is the exact center of the original square paper.

4. The Single Cut: Make a single straight cut across this corner (the center point of the original paper). This cut will remove a small triangular tip from all four layers simultaneously.

Unfolding and Result:

When you unfold the paper, the single cut will be reflected across both diagonal lines of symmetry. The removed triangular tip will open up to form a four-sided hole in the center. Because of the symmetrical folds along the diagonals, the resulting hole will be a square with its sides parallel to the edges of the paper.

Solution for Figure (b): Creating a Diamond (Rotated Square) Hole

Objective: To create a square hole in the center of the paper, rotated by 45 degrees to appear as a diamond.

Folding and Cutting Process:

1. First Fold: Take a square sheet of paper and fold it in half along its vertical line of symmetry.

2. Second Fold: Fold the resulting rectangle in half again, this time along its horizontal line of symmetry.

3. Result of Folding: You will now have a smaller square that is one-quarter the size of the original, with four layers of paper. The corner of this folded square that has no open edges (where both folds meet) is the center of the original paper.

4. The Single Cut: Make a single straight cut across this corner, removing a small triangular tip.

Unfolding and Result:

Upon unfolding the paper, the cut will be reflected across both the horizontal and vertical lines of symmetry. The removed tip will open up to form a four-sided hole. Because the folds were along the horizontal and vertical axes, the corners of the hole will lie on these axes, creating a square that is rotated by 45 degrees, appearing as a diamond.

Note on Verifying the Shape:

In both cases described above, the resulting four-sided hole is a perfect square. This is because the symmetrical folding process ensures that the straight cut creates four equal sides. Furthermore, the angles of the folds (90 degrees between horizontal/vertical axes, and 90 degrees between diagonals) ensure that all four interior angles of the hole are right angles (90°). A quadrilateral with four equal sides and four right angles is, by definition, a square.

i.

ii. A triangle with equal sides and equal angles.

iii. A hexagon with equal sides and equal angles.

Answer:

Solution

A line of symmetry is an imaginary line that divides a shape into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. We will find the number of such lines for each given shape.

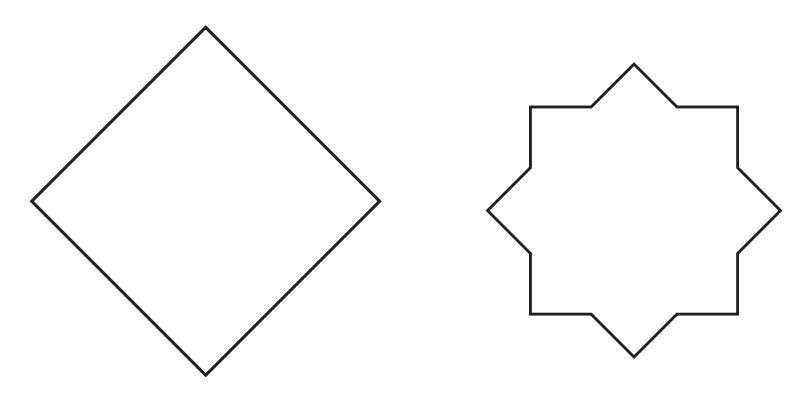

i. For the First Set of Shapes

Shape 1: The Square (Diamond)

This shape is a regular square, rotated by 45 degrees. A square has 4 lines of symmetry.

- Two lines of symmetry are its diagonals (which in this orientation are the horizontal and vertical lines passing through the center).

- The other two lines of symmetry connect the midpoints of opposite sides.

Shape 2: The Eight-Pointed Star

This is a regular eight-pointed star. It has 8 lines of symmetry.

- Four lines of symmetry pass through the pairs of opposite outer points (vertices) of the star.

- The other four lines of symmetry pass through the pairs of opposite inner corners (the bottom of the V-shapes) of the star.

ii. A Triangle with Equal Sides and Equal Angles

A triangle with equal sides and equal angles is called an equilateral triangle. An equilateral triangle has 3 lines of symmetry.

Each line of symmetry connects a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. This line is also the altitude and the angle bisector for that vertex.

iii. A Hexagon with Equal Sides and Equal Angles

A hexagon with equal sides and equal angles is called a regular hexagon. A regular hexagon has 6 lines of symmetry.

- Three lines of symmetry are the diagonals that connect opposite vertices.

- The other three lines of symmetry connect the midpoints of opposite sides.

Answer:

Solution

A line of symmetry is an imaginary line that divides a figure into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. Below are the lines of symmetry for each of the given figures.

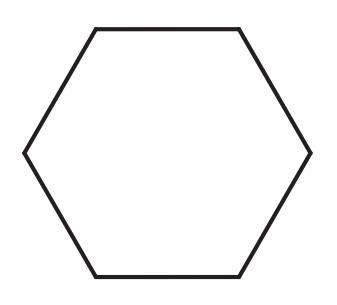

Figure (a)

This figure is composed of three diamonds in a pyramid arrangement.

It has only one line of symmetry, which is the vertical line passing through the center of the top diamond and between the two bottom diamonds.

Figure (b)

This figure shows three diamonds arranged in a horizontal row.

It has two lines of symmetry:

- A vertical line passing through the center of the middle diamond.

- A horizontal line passing through the middle of all three diamonds.

Figure (c)

This figure is composed of four diamonds arranged in a 2x2 grid, forming a larger diamond.

It has two lines of symmetry:

- One vertical line of symmetry.

- One horizontal line of symmetry.

Figure (d)

This figure shows four diamonds arranged in a cross or plus shape.

It has two lines of symmetry:

- One vertical line of symmetry.

- One horizontal line of symmetry.

Figure (e)

This figure shows two concentric squares on a grid.

It has four lines of symmetry:

- A vertical line through the center.

- A horizontal line through the center.

- Two diagonal lines connecting the opposite corners.

Figure (f)

This is an octagon drawn on a grid. It is symmetrical horizontally and vertically but is not a regular octagon.

It has two lines of symmetry:

- A vertical line through the center.

- A horizontal line through the center.

Figure (g)

This is a hexagon drawn on a grid. It is symmetrical horizontally and vertically.

It has one lines of symmetry:

- A horizontal line through the center.

Figure (h)

This figure is a four-pointed star drawn on a grid.

It has four lines of symmetry:

- A vertical line through the center.

- A horizontal line through the center.

- Two diagonal lines passing through the center and the inner corners.

Answer:

Solution

A line of symmetry is an imaginary line that divides a figure into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. The given kolam pattern is a highly symmetrical design with a hexagonal overall arrangement.

Upon careful observation of the kolam, we can identify that it has 6 lines of symmetry. These lines can be categorized into two groups, similar to the lines of symmetry in a regular hexagon.

The 6 lines of symmetry are:

1. Lines connecting the centers of opposite star patterns:

There are three such lines. These lines pass through the vertices of the overall hexagonal shape of the pattern.

- One horizontal line passing through the center of the entire design.

- Two diagonal lines, each passing through the centers of two opposite stars and the central star.

2. Lines passing through the midpoints of opposite sides of the hexagonal pattern:

There are also three lines of this type. These lines pass through the diamonds located between the star patterns.

- One vertical line passing through the center of the entire design.

- Two other diagonal lines that bisect the sides of the overall hexagonal arrangement.

The image below illustrates these 6 lines of symmetry drawn on the kolam pattern.

Therefore, the kolam figure has a total of six lines of symmetry.

Question 9. Draw the following.

a. A triangle with exactly one line of symmetry

b. A triangle with exactly three lines of symmetry

c. A triangle with no line of symmetry

Is it possible to draw a triangle with exactly two lines of symmetry?

Answer:

Here are the drawings and descriptions for triangles with the specified number of lines of symmetry:

a. A triangle with exactly one line of symmetry

This is an Isosceles Triangle (which is not equilateral).

An isosceles triangle has two equal sides and two equal angles. The single line of symmetry is the line that connects the vertex between the two equal sides to the midpoint of the third side (the base). This line is also the altitude to the base.

b. A triangle with exactly three lines of symmetry

This is an Equilateral Triangle.

An equilateral triangle has all three sides of equal length and all three angles are equal to $60^\circ$. It has three lines of symmetry. Each line of symmetry connects a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side.

c. A triangle with no line of symmetry

This is a Scalene Triangle.

A scalene triangle has three sides of different lengths and three angles of different measures. Because it has no equal sides or angles, there is no line that can divide it into two identical mirror-image halves.

Is it possible to draw a triangle with exactly two lines of symmetry?

No, it is not possible to draw a triangle with exactly two lines of symmetry.

Reasoning:

1. A line of symmetry in a triangle must pass through a vertex. This symmetry implies that the two sides meeting at that vertex are equal in length.

2. If a triangle has one line of symmetry, it must be an isosceles triangle.

3. If it were to have a second line of symmetry, that line must also pass through another vertex. This would mean that the two sides meeting at that second vertex must also be equal.

4. Let the sides of the triangle be A, B, and C. The first line of symmetry implies A = B. The second line of symmetry would imply that another pair of sides are equal, for example, B = C.

5. If A = B and B = C, then it must be that A = B = C. This means the triangle is equilateral.

6. An equilateral triangle does not have two lines of symmetry; it has three lines of symmetry. Therefore, any triangle with two lines of symmetry must necessarily have a third, making it impossible for a triangle to have exactly two.

Question 10. Draw the following. In each case, the figure should contain at least one curved boundary.

a. A figure with exactly one line of symmetry

b. A figure with exactly two lines of symmetry

c. A figure with exactly four lines of symmetry

Answer:

Here are examples of figures with at least one curved boundary and the specified number of lines of symmetry:

a. A figure with exactly one line of symmetry

A Semi-circle is a perfect example. It has a curved boundary (the arc) and a straight boundary (the diameter). The single line of symmetry is the perpendicular bisector of the diameter, which runs from the center of the diameter to the midpoint of the arc.

b. A figure with exactly two lines of symmetry

An Ellipse (or an oval) is a good example. The boundary is entirely curved. An ellipse has two perpendicular lines of symmetry: its major axis (the longest diameter) and its minor axis (the shortest diameter).

c. A figure with exactly four lines of symmetry

A four-leaf clover (quatrefoil) shape, formed by four identical semi-circles arranged symmetrically around a center point, is a good example. This figure has a fully curved boundary and possesses four lines of symmetry: one horizontal, one vertical, and two diagonal lines, all intersecting at the center.

Answer:

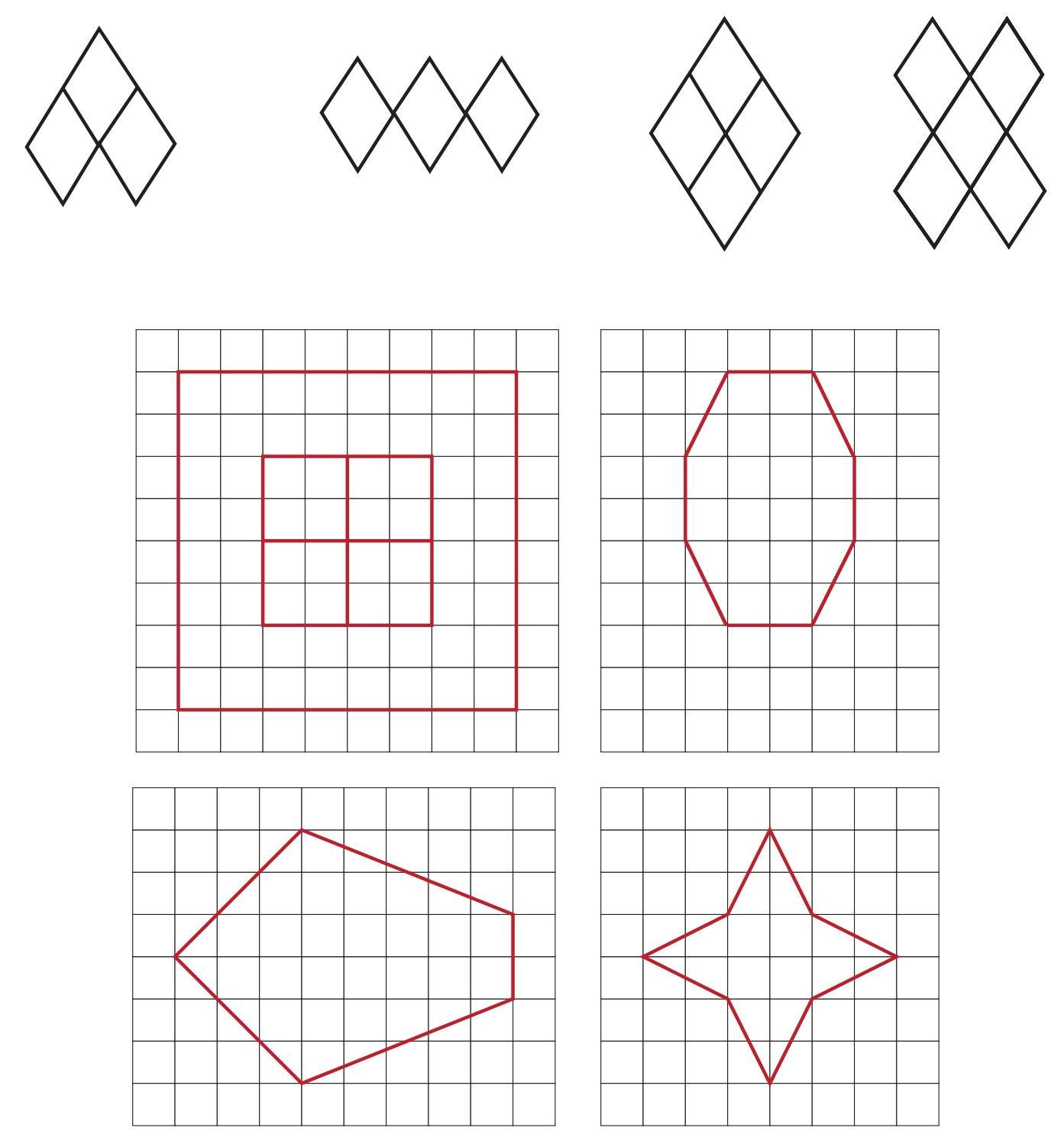

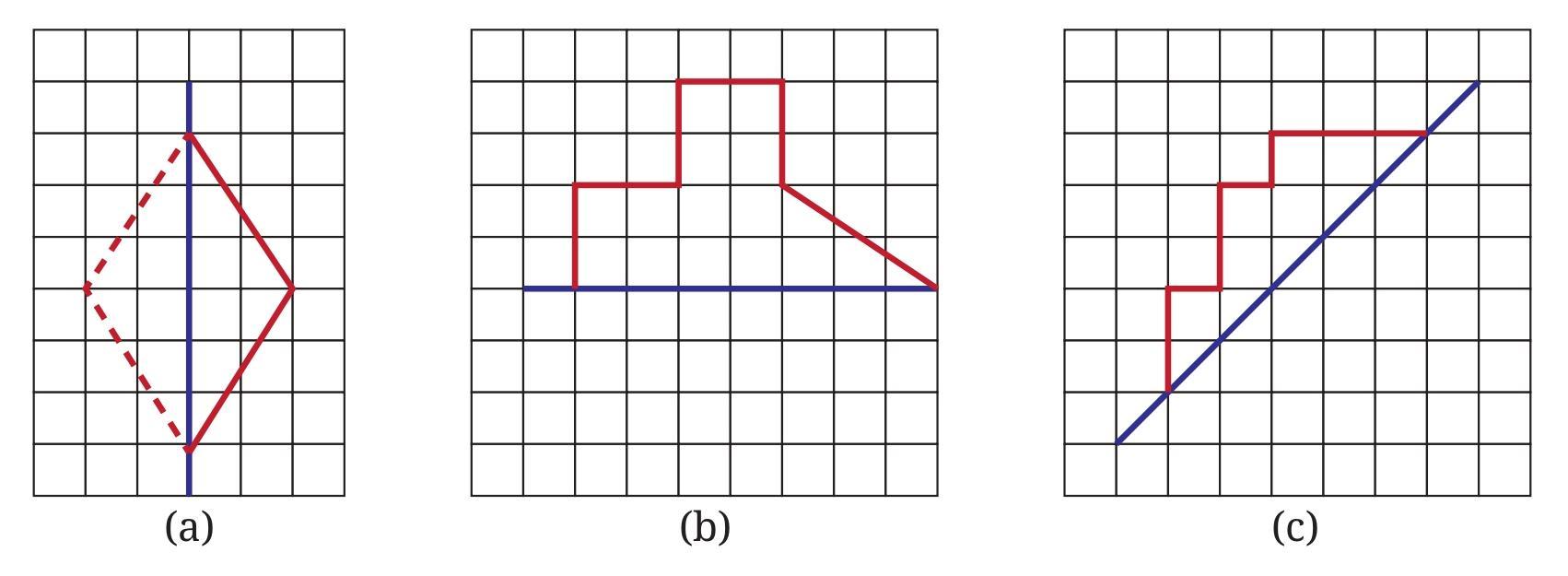

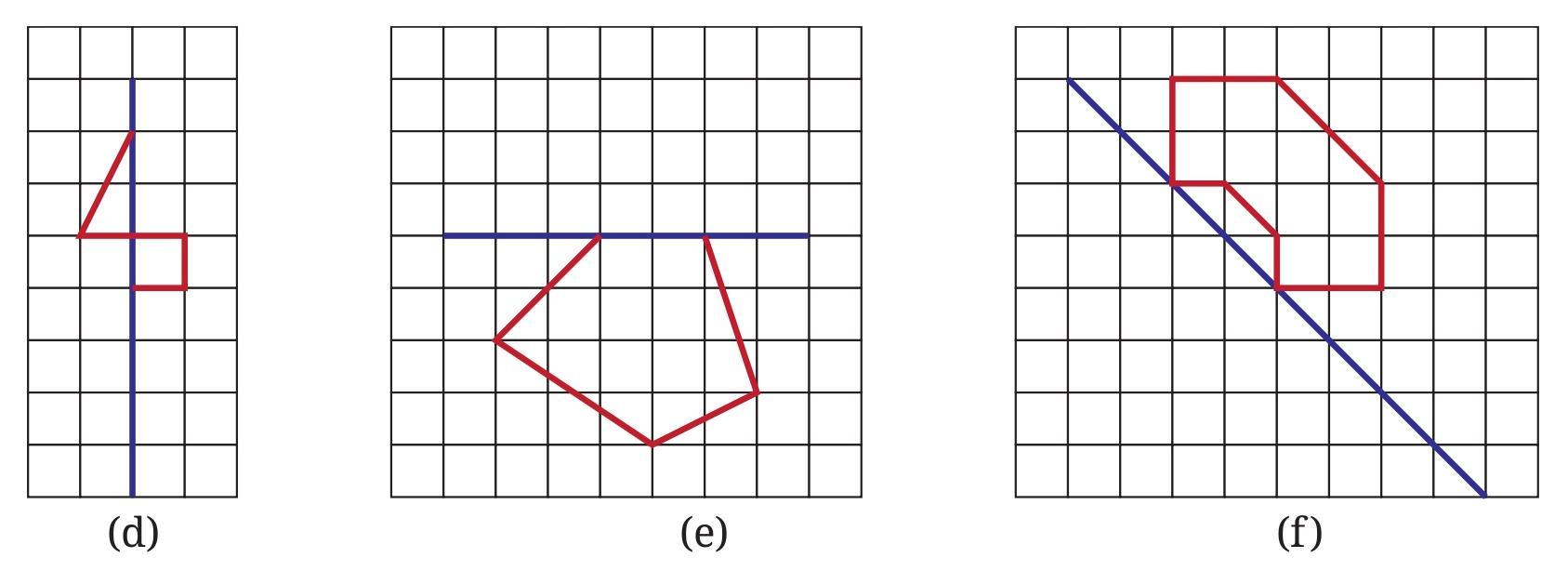

The figures are completed by reflecting the existing red shape across the blue line of symmetry. Each vertex of the new shape is the mirror image of the corresponding vertex in the original shape.

Solution for Figure (b)

The completed figure with the horizontal line of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (c)

The completed figure with the diagonal line of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (d)

The completed figure with the vertical line of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (e)

The completed figure with the horizontal line of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (f)

The completed figure with the diagonal line of symmetry is shown below.

Answer:

To complete each figure, the initial red shape must be reflected across both blue lines of symmetry. This is done by first reflecting the shape across one line, and then reflecting both the original shape and its reflection across the second line to fill all four quadrants symmetrically.

Solution for Figure (a)

The completed figure with two diagonal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (b)

The completed figure with two diagonal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (c)

The completed figure with vertical and horizontal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (d)

The completed figure with vertical and horizontal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (e)

The completed figure with vertical and horizontal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Solution for Figure (f)

The completed figure with vertical and horizontal lines of symmetry is shown below.

Answer:

The task is to complete each figure by adding lines to create a closed shape that has the specified line of symmetry, based on the descriptions provided. The original path will form part of the boundary of the final shape.

Figure 1: A quadrilateral with vertical line of symmetry

The original path forms two sides of a concave quadrilateral (an arrowhead). By adding two more lines to form the reflection, a symmetrical shape is created.

Figure 2: A convex hexagon with vertical line of symmetry

The original path forms part of the left side of the final shape. Its reflection forms the right side, and two new lines at the bottom complete the convex hexagon.

Figure 3: A concave hexagon with vertical line of symmetry

The original path is reflected across a vertical line, and the endpoints are connected to form a symmetrical concave hexagon.

Figure 4: A pentagon with vertical line of symmetry

The original path forms three sides on the left of a vertically symmetrical pentagon. Two more lines are added to complete the shape.

Figure 5: A concave pentagon with vertical line of symmetry

The original path forms two sides of a symmetrical concave pentagon, resembling the letter 'M'. The shape is completed by adding its reflection.

Figure 6: A convex pentagon with horizontal line of symmetry

The original path forms the upper part of a convex pentagon (an arrowhead pointing right). Reflecting this path downwards and connecting the endpoints completes the shape.

Figure it Out (Page 235 - 236)

Answer:

Solution

Rotational symmetry is a property a shape has when it looks the same after some rotation by a partial turn. The angle of symmetry (or angle of rotation) is the smallest angle you need to turn the figure for it to look the same as its original position. The order of rotational symmetry is the number of times the figure maps onto itself during a full $360^\circ$ rotation.

Figure (a)

This figure is in the shape of a plus sign (+).

If we rotate the figure about the marked central point, it will look identical to its original position after rotations of:

- $90^\circ$

- $180^\circ$

- $270^\circ$

The figure maps onto itself 4 times in a full $360^\circ$ rotation. Therefore, the smallest angle of symmetry is $90^\circ$ and the order of rotational symmetry is 4.

Figure (b)

This figure consists of a vertical line segment with two small squares attached. It is important to note that both squares are attached to the right side of the vertical line.

Let's consider rotating it by $180^\circ$ about the marked midpoint. The top end of the line will move to the bottom, and the bottom end will move to the top. The square that was at the top-right will now be at the bottom-left. The square that was at the bottom-right will now be at the top-left.

Since the squares are now on the left side of the line instead of the right, the figure does not look the same after a $180^\circ$ rotation. The figure only maps onto itself after a full $360^\circ$ rotation.

Therefore, the angle of symmetry is $360^\circ$ and the order of rotational symmetry is 1 (as it only matches its original position once).

Figure (c)

This figure is in the shape of the letter 'H'.

If we rotate the figure about the marked central point, it will look identical to its original position after a rotation of:

- $180^\circ$

The figure maps onto itself 2 times in a full $360^\circ$ rotation. Therefore, the angle of symmetry is $180^\circ$ and the order of rotational symmetry is 2.

Answer:

Solution

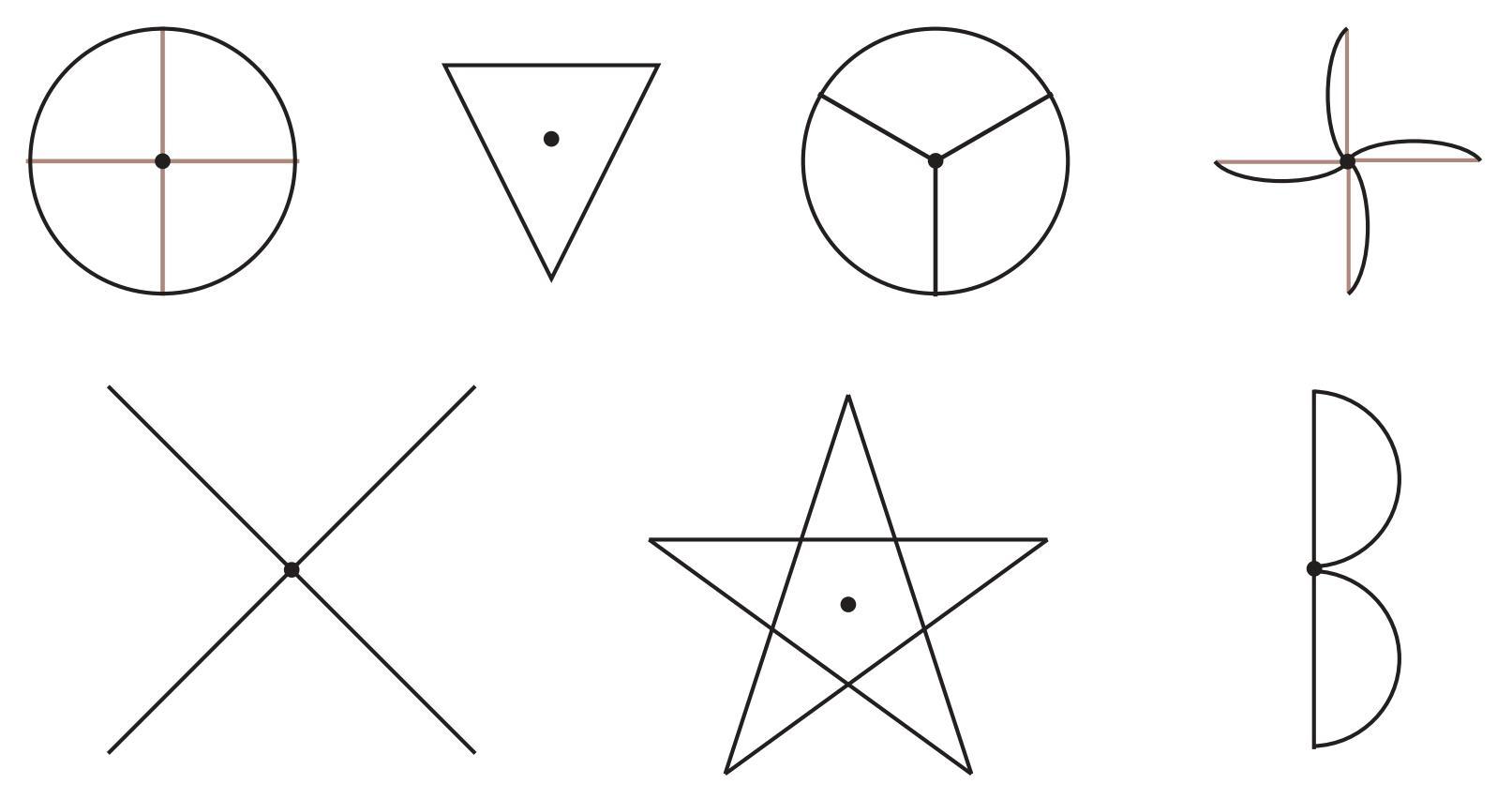

A figure has rotational symmetry if it looks the same after being rotated by an angle less than $360^\circ$ around a central point. The question asks to identify which of the given figures have more than one angle of symmetry. This means we are looking for figures that have an order of rotational symmetry of 3 or higher, as these figures will map onto themselves at multiple distinct angles during a full $360^\circ$ turn.

Let's analyze each figure:

Figure (i) - Circle with two perpendicular diameters:

This figure maps onto itself after rotations of $90^\circ$, $180^\circ$, and $270^\circ$. It has three distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 4.

Figure (ii) - Equilateral Triangle:

Assuming this is an equilateral triangle, it maps onto itself after rotations of $120^\circ$ and $240^\circ$. It has two distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 3.

Figure (iii) - Circle divided into three equal sectors:

This figure maps onto itself after rotations of $120^\circ$ and $240^\circ$. It has two distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 3.

Figure (iv) - Four-bladed pinwheel:

This figure maps onto itself after rotations of $90^\circ$, $180^\circ$, and $270^\circ$. It has three distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 4.

Figure (v) - Intersecting lines (X-shape):

This figure only maps onto itself after a rotation of $90^\circ$, $180^\circ$, and $270^\circ$. It has three distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 4.

Figure (vi) - Five-pointed star (Pentagram):

This figure maps onto itself after rotations of $72^\circ$, $144^\circ$, $216^\circ$, and $288^\circ$. It has four distinct angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 5.

Figure (vii) - B-shape:

This figure has no rotational symmetry. It only maps onto itself after a full $360^\circ$ rotation. It has no angles of symmetry. The order of rotational symmetry is 1.

Conclusion

The following figures have more than one angle of symmetry (i.e., an order of rotational symmetry of 3 or more):

| Figure | Order of Rotational Symmetry | Angles of Symmetry (< 360°) | Has more than one angle of symmetry? |

| (i) Circle with 4 quadrants | 4 | $90^\circ, 180^\circ, 270^\circ$ | Yes |

| (ii) Equilateral Triangle | 3 | $120^\circ, 240^\circ$ | Yes |

| (iii) Circle with 3 sectors | 3 | $120^\circ, 240^\circ$ | Yes |

| (iv) 4-bladed Pinwheel | 4 | $90^\circ, 180^\circ, 270^\circ$ | Yes |

| (v) Intersecting Lines (X) | 4 | $90^\circ, 180^\circ, 270^\circ$ | Yes |

| (vi) Pentagram | 5 | $72^\circ, 144^\circ, 216^\circ, 288^\circ$ | Yes |

| (vii) B-shape | 1 | None | No |

Therefore, figures (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and (vi) have more than one angle of symmetry.

Question 3. Give the order of rotational symmetry for each figure:

Let us list down the angles of symmetry for all the cases above .

- Angles of symmetry when there are exactly 2 of them: 180°, 360°.

- Angles of symmetry when there are exactly 3 of them: 120°, 240°, 360°.

- Angles of symmetry when there are exactly 4 of them: 90°, 180°, 270°, 360°.

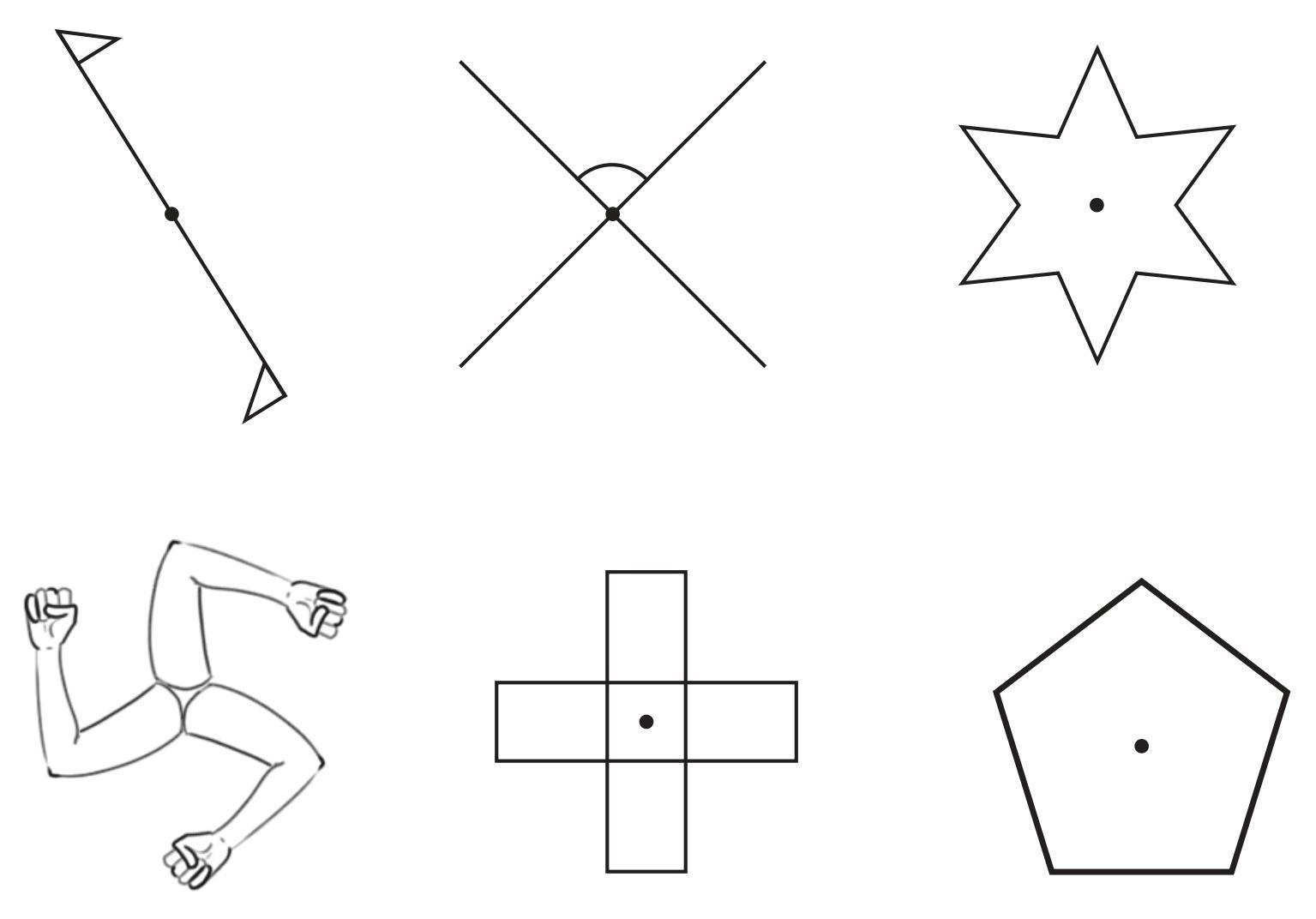

Answer:

Solution

The order of rotational symmetry is the number of times a figure maps onto itself during a full $360^\circ$ rotation about its center. An order of 1 means the figure has no rotational symmetry (it only looks the same after a full turn).

Here is the corrected order of rotational symmetry for each of the given figures:

| Figure | Description | Smallest Angle of Rotation | Order of Rotational Symmetry |

| (i) | A line segment with identical, oppositely pointing triangles at each end. | $180^\circ$ | 2 |

| (ii) | Two intersecting lines. | $180^\circ$ | 2 |

| (iii) | A regular six-pointed star. | $60^\circ$ | 6 |

| (iv) | A figure with three rotationally symmetric arms. | $120^\circ$ | 3 |

| (v) | A plus sign made of two identical rectangles. | $90^\circ$ | 4 |

| (vi) | A regular pentagon. | $72^\circ$ | 5 |

Explanation of Corrected Results

Figure (i): The figure looks the same after a half-turn ($180^\circ$). It maps onto itself twice in a full rotation. So, the order is 2.

Figure (ii): The figure consists of two intersecting lines. It maps onto itself after a rotation of $180^\circ$ because vertically opposite angles are equal. The small arc indicating one angle does not remove this symmetry. It maps onto itself twice in a full rotation. So, the order is 2.

Figure (iii): A regular six-pointed star has 6 identical points. It will look the same after being rotated by $60^\circ$ ($360^\circ / 6$). It maps onto itself 6 times. So, the order is 6.

Figure (iv): This figure has 3 identical arms arranged symmetrically around a central point. Therefore, it will map onto itself after a rotation of $120^\circ$ ($360^\circ / 3$). It maps onto itself 3 times in a full rotation. So, the order is 3.

Figure (v): The plus sign is symmetrical in four directions. It looks the same after rotations of $90^\circ$. It maps onto itself 4 times. So, the order is 4.

Figure (vi): A regular pentagon has 5 equal sides and angles. It will look the same after being rotated by $72^\circ$ ($360^\circ / 5$). It maps onto itself 5 times. So, the order is 5.

Figure it Out (Page 238)

Question 1. Color the sectors of the circle below so that the figure has

i) 3 angles of symmetry,

ii) 4 angles of symmetry,

iii) what are the possible numbers of angles of symmetry you can obtain by coloring the sectors in different ways?

Answer:

Solution

The circle is divided into 12 equal sectors. Each sector has an angle of $360^\circ / 12 = 30^\circ$. To achieve a specific rotational symmetry, we need to create a coloring pattern that repeats itself a certain number of times around the circle.

Note: The question uses the phrase "angles of symmetry". An "order of rotational symmetry of n" corresponds to "(n-1)" angles of symmetry less than $360^\circ$. For clarity, we will solve for the order of symmetry, which is the most common way to interpret such problems.

- "Order of symmetry 3" means the pattern repeats 3 times (every $120^\circ$), giving 2 angles of symmetry ($120^\circ, 240^\circ$).

- "Order of symmetry 4" means the pattern repeats 4 times (every $90^\circ$), giving 3 angles of symmetry ($90^\circ, 180^\circ, 270^\circ$).

We will assume part (i) asks for an order of 3 and part (ii) asks for an order of 4.

i) Order of Rotational Symmetry 3

To have an order of rotational symmetry of 3, the coloring pattern must repeat every $360^\circ / 3 = 120^\circ$.

Since the circle has 12 sectors, a rotation of $120^\circ$ corresponds to moving forward by $12 / 3 = 4$ sectors.

We can achieve this by creating a pattern within a block of 4 sectors and repeating it 3 times. For example, using two colors (e.g., Blue and Yellow):

Pattern: Color the first two sectors Blue and the next two sectors Yellow. Repeat this pattern for the entire circle.

ii) Order of Rotational Symmetry 4

To have an order of rotational symmetry of 4, the coloring pattern must repeat every $360^\circ / 4 = 90^\circ$.

This corresponds to moving forward by $12 / 4 = 3$ sectors.

We can achieve this by creating a pattern within a block of 3 sectors and repeating it 4 times. For example, using two colors (e.g., Green and Red):

Pattern: Color the first sector Green and the next two sectors Red. Repeat this pattern for the entire circle.

iii) Possible Numbers of Angles of Symmetry

The possible orders of rotational symmetry for a figure with 12 equal parts are determined by the divisors of 12.

The divisors of 12 are 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12.

These are the possible orders of rotational symmetry we can create. Each order corresponds to a specific number of angles of symmetry (which is the order minus one). The possible numbers are:

| Order of Rotational Symmetry | Pattern Repeats Every... | Number of Angles of Symmetry (< 360°) |

| 1 | 12 sectors (asymmetric coloring) | 0 |

| 2 | 6 sectors | 1 |

| 3 | 4 sectors | 2 |

| 4 | 3 sectors | 3 |

| 6 | 2 sectors (e.g., alternating colors) | 5 |

| 12 | 1 sector (all sectors same color) | 11 |

Therefore, the possible numbers of angles of symmetry you can obtain are 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 11.

Question 2. Draw two figures other than a circle and a square that have both reflection symmetry and rotational symmetry.

Here are two figures, other than a circle and a square, that possess both reflection (line) symmetry and rotational symmetry:

Figure 1: An Equilateral Triangle

An equilateral triangle is a triangle in which all three sides have the same length and all three angles are $60^\circ$.

- Reflection Symmetry: It has 3 lines of symmetry. Each line passes from a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side.

- Rotational Symmetry: It has rotational symmetry of order 3. The triangle looks identical after being rotated by $120^\circ$ and $240^\circ$ about its center.

Figure 2: A Regular Hexagon

A regular hexagon is a six-sided polygon with all sides of equal length and all internal angles equal to $120^\circ$.

- Reflection Symmetry: It has 6 lines of symmetry. Three lines connect opposite vertices, and the other three connect the midpoints of opposite sides.

- Rotational Symmetry: It has rotational symmetry of order 6. The hexagon looks identical after rotations by multiples of $60^\circ$ ($60^\circ, 120^\circ, 180^\circ, 240^\circ, 300^\circ$) about its center.

Question 3. Draw, wherever possible, a rough sketch of

a. A triangle with at least two lines of symmetry and at least two angles of symmetry.

b. A triangle with only one line of symmetry but not having rotational symmetry.

c. A quadrilateral with rotational symmetry but no reflection symmetry.

d. A quadrilateral with reflection symmetry but not having rotational symmetry.

Here are the rough sketches and descriptions for the requested figures:

a. A triangle with at least two lines of symmetry and at least two angles of symmetry.

A triangle with two lines of symmetry must necessarily have a third. This is an equilateral triangle. An equilateral triangle has 3 lines of symmetry and rotational symmetry of order 3 (meaning it has two angles of symmetry less than $360^\circ$: $120^\circ$ and $240^\circ$).

b. A triangle with only one line of symmetry but not having rotational symmetry.

This is an isosceles triangle (that is not equilateral). It has one line of symmetry. Its rotational symmetry is of order 1, which means it only looks the same after a full $360^\circ$ turn, so it does not have rotational symmetry in the usual sense.

c. A quadrilateral with rotational symmetry but no reflection symmetry.

This is a parallelogram that is neither a rectangle nor a rhombus. It has rotational symmetry of order 2 (it looks the same after a $180^\circ$ turn) but has no lines of symmetry.

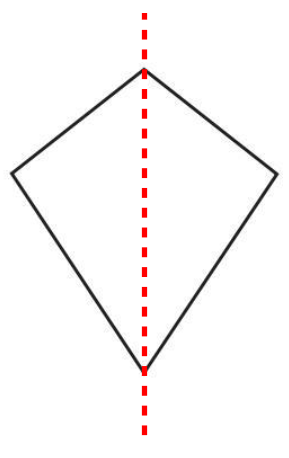

d. A quadrilateral with reflection symmetry but not having rotational symmetry.

A kite or an isosceles trapezoid fits this description. Both have one line of reflection symmetry but have rotational symmetry of order 1 (no rotational symmetry).

Question 4. In a figure, 60° is the smallest angle of symmetry. What are the other angles of symmetry of this figure?

If the smallest angle of rotational symmetry for a figure is $60^\circ$, then all other angles of symmetry must be integer multiples of this smallest angle, up to $360^\circ$.

The angles of symmetry are given by $n \times 60^\circ$, where $n$ is an integer from 1 to 6.

- $1 \times 60^\circ = 60^\circ$ (The smallest angle)

- $2 \times 60^\circ = 120^\circ$

- $3 \times 60^\circ = 180^\circ$

- $4 \times 60^\circ = 240^\circ$

- $5 \times 60^\circ = 300^\circ$

- $6 \times 60^\circ = 360^\circ$ (The full rotation)

The question asks for the other angles of symmetry, which are all the multiples except for the smallest one.

Therefore, the other angles of symmetry are $120^\circ$, $180^\circ$, $240^\circ$, $300^\circ$, and $360^\circ$. A figure like a regular hexagon has this property.

Question 5. In a figure, 60° is an angle of symmetry. The figure has two angles of symmetry less than 60°. What is its smallest angle of symmetry?

Let's solve this puzzle step-by-step! Imagine we have a shape that we are spinning around its center.

What We Know:

1. The shape looks exactly the same after a $60^\circ$ turn.

2. There are two other turns, smaller than $60^\circ$, that also make the shape look the same.

Thinking it Through:

The key idea is that all the "magic" turning angles for a shape are just steps of the same size. We just need to find the size of the smallest step (the smallest angle).

Since a $60^\circ$ turn works, our smallest step must fit perfectly into $60^\circ$ a certain number of times. Let's list the numbers that divide 60 evenly:

The possible sizes for our "smallest step" are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, 60.

Now, let's use our second clue: there must be exactly two steps that are smaller than $60^\circ$. Let's test some of our possible step sizes:

- What if the smallest step is $30^\circ$? The steps would be $30^\circ$, then $60^\circ$, then $90^\circ$ ... How many steps are smaller than $60^\circ$? Only one ($30^\circ$). So, this can't be our answer.

- What if the smallest step is $20^\circ$? The steps would be $20^\circ$, then $40^\circ$, then $60^\circ$ ... How many steps are smaller than $60^\circ$? There are two! ($20^\circ$ and $40^\circ$). This matches our clue perfectly!

- What if the smallest step is $15^\circ$? The steps would be $15^\circ$, $30^\circ$, $45^\circ$, $60^\circ$ ... How many steps are smaller than $60^\circ$? There are three ($15^\circ, 30^\circ, 45^\circ$). That's too many.

Only the step size of $20^\circ$ gives us exactly two angles of symmetry less than $60^\circ$.

Conclusion:

The smallest angle of symmetry for the figure must be $20^\circ$.

Question 6. Can we have a figure with rotational symmetry whose smallest angle of symmetry is

a. 45°

b. 17°

A figure can have a smallest angle of rotational symmetry $\alpha$ only if $\alpha$ is a divisor of $360^\circ$. This is because a full $360^\circ$ rotation must map the figure onto itself, so $360^\circ$ must be an integer multiple of the smallest angle $\alpha$.

a. 45°

We check if $45^\circ$ is a divisor of $360^\circ$.

$360 \div 45 = 8$

Since the result is an integer (8), it is possible.

Yes, a figure can have $45^\circ$ as its smallest angle of symmetry. An example is a regular octagon, which has rotational symmetry of order 8.

b. 17°

We check if $17^\circ$ is a divisor of $360^\circ$.

$360 \div 17 \approx 21.176$

Since the result is not an integer, it is not possible for $17^\circ$ to be the smallest angle of symmetry for any figure.

No, because $360$ is not divisible by $17$.

Question 7. This is a picture of the new Parliament Building in Delhi.

a. Does the outer boundary of the picture have reflection symmetry? If so, draw the lines of symmetries. How many are they?

b. Does it have rotational symmetry around its centre? If so, find the angles of rotational symmetry.

Answer:

The question asks us to analyze the symmetry of the outer boundary of the new Parliament Building. The idealized geometric shape of the building's footprint is created by truncating the three corners of an equilateral triangle with identical smaller triangles. This process preserves the original symmetries of the equilateral triangle.

a. Does the outer boundary of the picture have reflection symmetry? If so, draw the lines of symmetries. How many are they?

Yes, the outer boundary has reflection symmetry.

Since the shape is derived from an equilateral triangle by performing identical cuts on each of its three vertices, it inherits the reflectional symmetries of the parent triangle.

An equilateral triangle has three lines of symmetry, each passing through a vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side. The resulting hexagon also has three lines of symmetry. Each line of symmetry connects the midpoint of a longer side to the midpoint of the opposite shorter side.

b. Does it have rotational symmetry around its centre? If so, find the angles of rotational symmetry.

Yes, the figure has rotational symmetry.

Just like its reflectional symmetry, the shape's rotational symmetry is also inherited from the parent equilateral triangle. An equilateral triangle has a rotational symmetry of order 3.

Therefore, the building's outline also has rotational symmetry of order 3. This means the figure will look identical to its original position after being rotated by multiples of $360^\circ / 3 = 120^\circ$.

The angles of rotational symmetry (less than $360^\circ$) are:

- $120^\circ$

- $240^\circ$

Question 8. How many lines of symmetry do the shapes in the first shape sequence in Chapter 1, Table 3, the Regular Polygons, have? What number sequence do you get?

| Table 3 Examples of Shape Sequences | |

|---|---|

| Regular Polygons | .jpg)

|

Answer:

The first shape sequence from Chapter 1, Table 3 is the sequence of Regular Polygons. These are shapes where all sides are of equal length and all angles are equal.

The rule for the number of lines of symmetry in a regular polygon is very simple:

A regular polygon with 'n' sides has 'n' lines of symmetry.

Let's look at the first few regular polygons in the sequence:

| Regular Polygon | Number of Sides (n) | Number of Lines of Symmetry |

| Equilateral Triangle | 3 | 3 |

| Square | 4 | 4 |

| Regular Pentagon | 5 | 5 |

| Regular Hexagon | 6 | 6 |

| Regular Heptagon | 7 | 7 |

| Regular Octagon | 8 | 8 |

| Regular Nonagon | 9 | 9 |

| Regular Decagon | 10 | 10 |

By listing the number of lines of symmetry for each shape in order, we get a number sequence.

The number sequence is: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Question 9. How many angles of symmetry do the shapes in the first shape sequence in Chapter 1, Table 3, the Regular Polygons, have? What number sequence do you get?

| Table 3 Examples of Shape Sequences | |

|---|---|

| Regular Polygons | .jpg)

|

Answer:

The sequence of shapes is the Regular Polygons (Equilateral Triangle, Square, Regular Pentagon, etc.).

The "number of angles of symmetry" is another way of asking for the order of rotational symmetry. This is the number of times a shape looks exactly the same as it spins one full circle ($360^\circ$).

The rule for rotational symmetry in a regular polygon is:

A regular polygon with 'n' sides has a rotational symmetry of order 'n'.

Let's look at the first few regular polygons:

| Regular Polygon | Number of Sides (n) | Order of Rotational Symmetry |

| Equilateral Triangle | 3 | 3 |

| Square | 4 | 4 |

| Regular Pentagon | 5 | 5 |

| Regular Hexagon | 6 | 6 |

| Regular Heptagon | 7 | 7 |

| Regular Octagon | 8 | 8 |

| Regular Nonagon | 9 | 9 |

| Regular Decagon | 10 | 10 |

By listing the order of rotational symmetry for each shape in the sequence, we get a number sequence.

The number sequence is: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Question 10. How many lines of symmetry do the shapes in the last shape sequence in Chapter 1, Table 3, the Koch Snowflake sequence, have? How many angles of symmetry?

| Table 3 Examples of Shape Sequences | |

|---|---|

| Koch Snowflake | .jpg)

|

Answer:

Your observation that the number of symmetries changes is correct, which is a key insight. However, the exact numbers are slightly different. Let's analyze each step of the sequence shown.

Step 1: The Equilateral Triangle

- Lines of Symmetry: As you correctly noted, the starting equilateral triangle has 3 lines of symmetry.

- Angles of Symmetry (Order of Rotation): It has rotational symmetry of order 3.

Step 2: The Six-Pointed Star (Hexagram)

This shape is created by adding a new equilateral triangle to the middle of each of the 3 sides of the first triangle. This new shape is highly symmetrical.

- Lines of Symmetry: This shape actually has 6 lines of symmetry. Three lines pass through the opposite points of the star, and three lines pass through the opposite "dips" or inner corners. A shape cannot have 5 lines of symmetry.

- Angles of Symmetry (Order of Rotation): It has rotational symmetry of order 6, as it looks the same after every $60^\circ$ turn.

Step 3 and Beyond: The Rest of the Figures

From the six-pointed star onwards, the construction process involves adding smaller triangles to every available side. This process is done in a way that preserves the symmetry of the six-pointed star.

- Lines of Symmetry: The 6 lines of symmetry from the star shape are maintained in all the more complex stages.

- Angles of Symmetry (Order of Rotation): The rotational symmetry of order 6 is also maintained throughout the rest of the sequence.

Summary

The number of symmetries is not constant throughout the entire sequence. It changes from the first shape to the second, and then stays the same.

- For the first shape (triangle): There are 3 lines of symmetry and 3 angles of symmetry (order 3).

- For all subsequent shapes (star and beyond): There are 6 lines of symmetry and 6 angles of symmetry (order 6).

Answer:

Solution

The Ashoka Chakra is the wheel depicted in the centre of the national flag of India. It is a highly symmetrical figure, representing the Dharma Chakra. It has 24 equally spaced spokes.

Lines of Symmetry (Reflection Symmetry)

A line of symmetry is a line that divides a figure into two identical halves that are mirror images of each other. The Ashoka Chakra has 24 lines of symmetry. These can be understood in two groups:

- Lines passing through opposite spokes: A line can be drawn through the center of the Chakra and along the middle of any pair of opposite spokes. Since there are 24 spokes, there are 12 pairs of opposite spokes. This gives 12 lines of symmetry.

- Lines passing between opposite spokes: A line can also be drawn through the center of the Chakra, exactly in the middle of the gap between any two adjacent spokes. This line will also pass through the middle of the opposite gap. Since there are 24 gaps, there are 12 pairs of opposite gaps. This gives another 12 lines of symmetry.

In total, there are $12 + 12 = 24$ lines of symmetry.

Angles of Symmetry (Rotational Symmetry)

The "number of angles of symmetry" refers to the order of rotational symmetry. This is the number of times the figure looks identical during a full $360^\circ$ rotation.

The Ashoka Chakra has 24 spokes that are placed at equal angles from each other. The smallest angle of rotation that will make the Chakra look identical to its starting position is the angle between any two adjacent spokes.

We can calculate this smallest angle:

$\text{Smallest Angle of Symmetry} = \frac{360^\circ}{24} = 15^\circ$

Since the Chakra looks the same after every $15^\circ$ rotation, the number of times it maps onto itself in a full $360^\circ$ turn is:

$\text{Order of Symmetry} = \frac{360^\circ}{15^\circ} = 24$

Therefore, the Ashoka Chakra has 24 angles of symmetry (or, an order of rotational symmetry of 24).

Summary

| Type of Symmetry | Count |

| Number of Lines of Symmetry | 24 |

| Number of Angles of Symmetry (Order of Rotation) | 24 |