| Latest Maths NCERT Books Solution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

Chapter 5 Prime Time

Welcome to the solution guide for Chapter 5, "Prime Time," a pivotal chapter within the Class 6 Ganita Prakash textbook prescribed by NCERT for the 2024-25 academic session. This chapter significantly deepens the exploration of numbers, focusing specifically on the fascinating and fundamental category of prime numbers and their counterparts, composite numbers. Building upon potentially introductory concepts from earlier studies (like Chapter 3, "Number Play"), these solutions are meticulously crafted to enhance students' understanding, providing clarity and detailed methods for the exercises presented.

The core objective here is to move beyond basic identification and delve into the unique properties that distinguish prime numbers (numbers greater than 1 with exactly two distinct positive divisors: 1 and themselves, like $2, 3, 5, 7, 11, \dots$) from composite numbers (numbers greater than 1 that have more than two factors, like $4, 6, 8, 9, 10, \dots$). The solutions provided offer comprehensive support for exercises designed to solidify this distinction. Students can expect detailed explanations and worked examples focused on systematically identifying prime numbers within a given range. This often involves demonstrating practical techniques such as the Sieve of Eratosthenes, an ancient and effective algorithm for filtering out composite numbers to reveal the primes up to a specific limit.

Beyond the basic definitions, "Prime Time" often introduces related intriguing concepts. The solutions will likely provide clear definitions and illustrative examples for:

- Twin Primes: Pairs of prime numbers that have a difference of exactly 2. Examples include $(3, 5)$, $(5, 7)$, $(11, 13)$, and $(17, 19)$.

- Co-primes (or Relatively Prime numbers): Pairs of numbers whose highest common factor (HCF) is only 1. They don't need to be prime themselves, for instance, $8$ and $15$ are co-prime.

- Perfect Numbers: Although less common at this level, sometimes introduced; these are numbers that are equal to the sum of their proper positive divisors (e.g., $6 = 1 + 2 + 3$).

A central pillar, revisited and reinforced in this chapter, is the concept of prime factorization. This fundamental idea states that every composite number can be expressed as a unique product of its prime factors. The solutions will demonstrate this process clearly, possibly applying it to larger numbers than previously encountered, breaking them down into their prime building blocks (e.g., $84 = 2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 7 = 2^2 \times 3 \times 7$). The uniqueness of this factorization, informally known as the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, is implicitly underscored. Furthermore, the solutions will expertly guide students through various problem types, such as devising tests to determine if a given number is prime, applying the properties of primes to solve numerical puzzles, or investigating interesting patterns related to the distribution or behavior of prime numbers. By carefully studying these detailed solutions for Chapter 5 of the Class 6 Ganita Prakash (2024-25), students will gain a more profound appreciation for the foundational role prime numbers play across mathematics, refine their factorization skills, learn systematic identification methods, and strengthen their overall number sense and analytical thinking capabilities.

Figure it Out (Page 108)

Question 1. At what number is ‘idli-vada’ said for the 10th time?

Answer:

Given:

In the Idli-Vada game:

1. The players say 'idli' for the multiples of 3 (e.g., 3, 6, 9, ...).

2. The players say 'vada' for the multiples of 5 (e.g., 5, 10, 20, ...).

3. The players say 'idli-vada' for the numbers which are multiples of both 3 and 5.

To Find:

The number at which ‘idli-vada’ is said for the 10th time.

Solution:

The phrase 'idli-vada' is said for numbers that are multiples of both 3 and 5. These numbers are the common multiples of 3 and 5.

To find the common multiples, we first need to find the Least Common Multiple (LCM) of 3 and 5.

Since 3 and 5 are both prime numbers, their LCM is their product.

$LCM(3, 5) = 3 \times 5 = 15$

This means that 'idli-vada' is said for all the multiples of 15.

The 1st time 'idli-vada' is said is at the number $1 \times 15 = 15$.

The 2nd time 'idli-vada' is said is at the number $2 \times 15 = 30$.

The 3rd time 'idli-vada' is said is at the number $3 \times 15 = 45$.

Following this pattern, the $n^{th}$ time 'idli-vada' is said will be at the number $n \times 15$.

We need to find the number for the 10th time.

So, we set $n = 10$.

The required number = $10 \times 15 = 150$.

Therefore, ‘idli-vada’ is said for the 10th time at the number 150.

Question 2. If the game is played for the numbers from 1 till 90, find out:

a. How many times would the children say ‘idli’ (including the times they say ‘idli-vada’)?

b. How many times would the children say ‘vada’ (including the times they say ‘idli-vada’)?

c. How many times would the children say ‘idli-vada’?

Answer:

Given:

The Idli-Vada game is played with numbers from 1 to 90.

1. 'Idli' is said for multiples of 3.

2. 'Vada' is said for multiples of 5.

3. 'Idli-vada' is said for multiples of both 3 and 5.

To Find:

a. The number of times 'idli' is said (including 'idli-vada').

b. The number of times 'vada' is said (including 'idli-vada').

c. The number of times 'idli-vada' is said.

Solution:

a. How many times would the children say ‘idli’?

The word 'idli' is said for any number that is a multiple of 3. To find how many multiples of 3 are there from 1 to 90, we divide 90 by 3.

Number of times 'idli' is said = $\lfloor \frac{90}{3} \rfloor = 30$

Thus, the children would say ‘idli’ 30 times.

b. How many times would the children say ‘vada’?

The word 'vada' is said for any number that is a multiple of 5. To find how many multiples of 5 are there from 1 to 90, we divide 90 by 5.

Number of times 'vada' is said = $\lfloor \frac{90}{5} \rfloor = 18$

Thus, the children would say ‘vada’ 18 times.

c. How many times would the children say ‘idli-vada’?

The phrase 'idli-vada' is said for numbers that are multiples of both 3 and 5. These are the common multiples of 3 and 5, which are the multiples of their Least Common Multiple (LCM).

First, we find the LCM of 3 and 5.

$LCM(3, 5) = 15$

Now, we find how many multiples of 15 are there from 1 to 90 by dividing 90 by 15.

Number of times 'idli-vada' is said = $\lfloor \frac{90}{15} \rfloor = 6$

Thus, the children would say ‘idli-vada’ 6 times.

Question 3. What if the game was played till 900? How would your answers change?

Answer:

Given:

The Idli-Vada game is now played with numbers from 1 to 900.

Solution:

We will use the same logic as before, but with the upper limit of 900.

a. Number of times ‘idli’ is said:

This is the number of multiples of 3 from 1 to 900.

Number of multiples of 3 = $\lfloor \frac{900}{3} \rfloor = 300$

The children would say ‘idli’ 300 times.

b. Number of times ‘vada’ is said:

This is the number of multiples of 5 from 1 to 900.

Number of multiples of 5 = $\lfloor \frac{900}{5} \rfloor = 180$

The children would say ‘vada’ 180 times.

c. Number of times ‘idli-vada’ is said:

This is the number of multiples of 15 (LCM of 3 and 5) from 1 to 900.

Number of multiples of 15 = $\lfloor \frac{900}{15} \rfloor = 60$

The children would say ‘idli-vada’ 60 times.

Comparison and Changes:

The range of the game increased from 90 to 900, which is a factor of 10. Consequently, the number of times each word/phrase is said also increases by a factor of 10.

| Word/Phrase | Count (up to 90) | Count (up to 900) | Change Factor |

| ‘idli’ | 30 | 300 | $\times 10$ |

| ‘vada’ | 18 | 180 | $\times 10$ |

| ‘idli-vada’ | 6 | 60 | $\times 10$ |

Question 4.

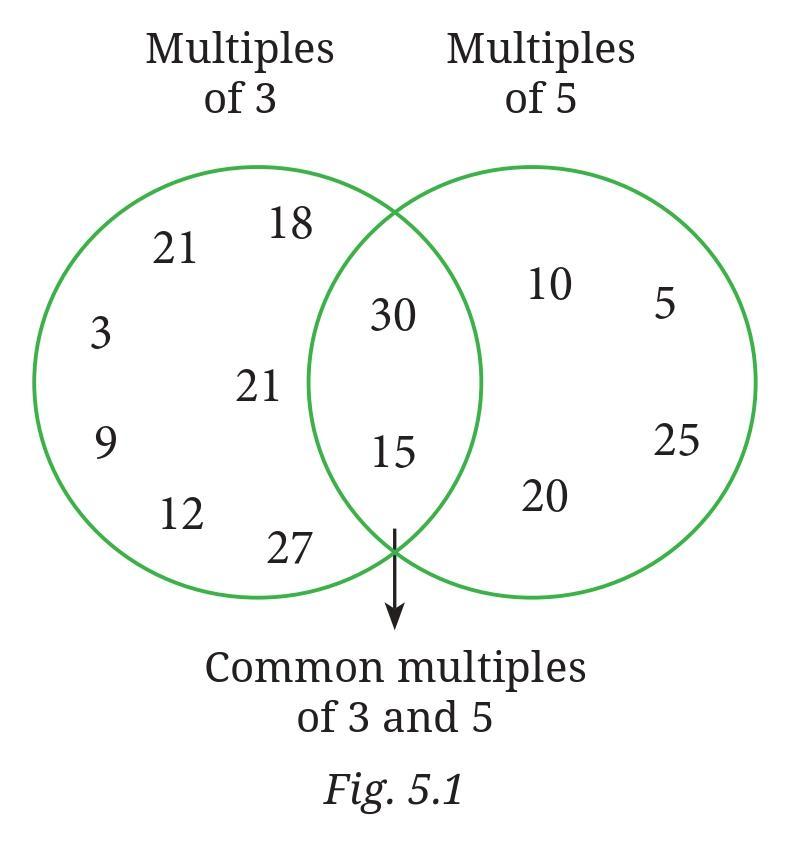

Is this figure somehow related to the ‘idli-vada’ game?

Hint: Imagine playing the game till 30. Draw the figure if the game is played till 60.

Answer:

Yes, the figure is a Venn diagram and it is directly related to the ‘idli-vada’ game. It visually represents the relationship between the sets of numbers in the game.

- The first circle represents the set of numbers that are Multiples of 3 (where 'idli' is said).

- The second circle represents the set of numbers that are Multiples of 5 (where 'vada' is said).

- The overlapping region (intersection) of the two circles represents the set of numbers that are Common multiples of 3 and 5 (where 'idli-vada' is said).

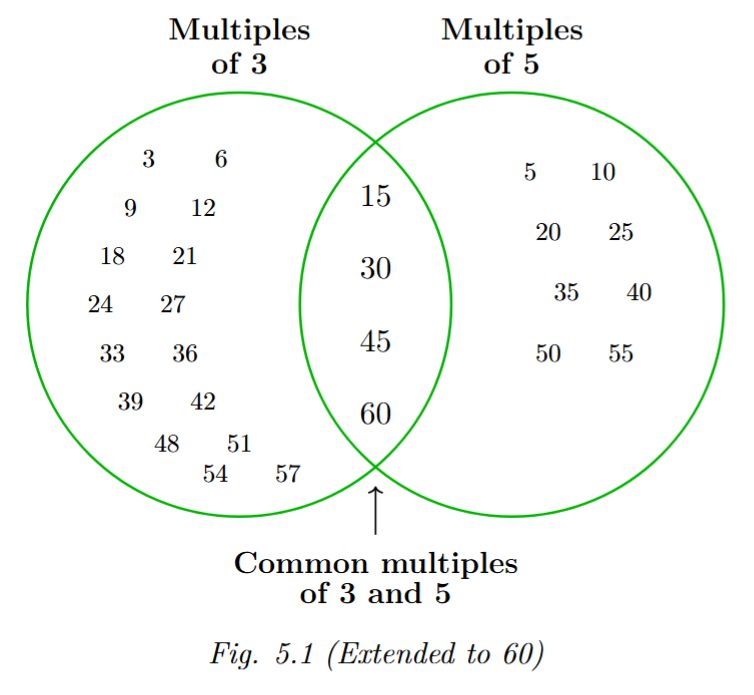

Figure for the game played till 60:

To draw the figure for the game played till 60, we first need to find the number of elements in each part of the Venn diagram.

1. Total Multiples of 3 (for the 'idli' circle):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{3} \rfloor = 20$

2. Total Multiples of 5 (for the 'vada' circle):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{5} \rfloor = 12$

3. Common Multiples of 3 and 5 (Multiples of 15, for the intersection):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{15} \rfloor = 4$

The common multiples are 15, 30, 45, and 60.

Now, we can determine the number of elements in each specific region of the diagram:

- Only Multiples of 3 (numbers where only 'idli' is said):

Total Multiples of 3 - Common Multiples = $20 - 4 = 16$

- Only Multiples of 5 (numbers where only 'vada' is said):

Total Multiples of 5 - Common Multiples = $12 - 4 = 8$

- Common Multiples of both 3 and 5 (numbers where 'idli-vada' is said):

Count = 4

The Venn diagram for the game played till 60 would look like this:

This figure visually confirms the calculations and shows how the different sets of numbers in the game are related.

Intext Question (Page 108)

Question: Let us now play the ‘idli-vada’ game with different pairs of numbers:

a. 2 and 5,

b. 3 and 7,

c. 4 and 6.

We will say ‘idli’ for multiples of the smaller number, ‘vada’ for multiples of the larger number and ‘idli-vada’ for common multiples. Draw a figure similar to Fig. 5.1 if the game is played up to 60.

Answer:

We will analyze the game for each pair of numbers by calculating the number of multiples up to 60. This will allow us to determine the values for a Venn diagram representation for each case.

a. For the pair of numbers 2 and 5

In this version of the game, played up to 60:

- 'Idli' is said for multiples of the smaller number, which is 2.

- 'Vada' is said for multiples of the larger number, which is 5.

- 'Idli-vada' is said for common multiples of 2 and 5.

First, we find the LCM of 2 and 5 to identify the numbers for 'idli-vada'. Since 2 and 5 are prime numbers, their LCM is their product.

$LCM(2, 5) = 2 \times 5 = 10$

Now, we calculate the number of times each term is said up to 60.

1. Total times 'idli' is said (Multiples of 2):

Count = $\frac{60}{2} = 30$

2. Total times 'vada' is said (Multiples of 5):

Count = $\frac{60}{5} = 12$

3. Times 'idli-vada' is said (Multiples of 10):

Count = $\frac{60}{10} = 6$

For the Venn diagram figure, we find the counts for the exclusive regions:

- Only 'idli' (Multiples of 2 but not 5): $30 - 6 = 24$

- Only 'vada' (Multiples of 5 but not 2): $12 - 6 = 6$

- 'Idli-vada' (Multiples of 10): $6$

The figure for this game would have:

b. For the pair of numbers 3 and 7

In this version of the game, played up to 60:

- 'Idli' is said for multiples of the smaller number, which is 3.

- 'Vada' is said for multiples of the larger number, which is 7.

- 'Idli-vada' is said for common multiples of 3 and 7.

First, we find the LCM of 3 and 7. Since 3 and 7 are prime numbers, their LCM is their product.

$LCM(3, 7) = 3 \times 7 = 21$

Now, we calculate the number of times each term is said up to 60.

1. Total times 'idli' is said (Multiples of 3):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{3} \rfloor = 20$

2. Total times 'vada' is said (Multiples of 7):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{7} \rfloor = 8$

3. Times 'idli-vada' is said (Multiples of 21):

Count = $\lfloor \frac{60}{21} \rfloor = 2$

(The numbers are 21, 42)

For the Venn diagram figure, we find the counts for the exclusive regions:

- Only 'idli' (Multiples of 3 but not 7): $20 - 2 = 18$

- Only 'vada' (Multiples of 7 but not 3): $8 - 2 = 6$

- 'Idli-vada' (Multiples of 21): $2$

The figure for this game would have:

c. For the pair of numbers 4 and 6

In this version of the game, played up to 60:

- 'Idli' is said for multiples of the smaller number, which is 4.

- 'Vada' is said for multiples of the larger number, which is 6.

- 'Idli-vada' is said for common multiples of 4 and 6.

First, we find the LCM of 4 and 6.

Prime factors of 4 are $2 \times 2 = 2^2$.

Prime factors of 6 are $2 \times 3$.

$LCM(4, 6) = 2^2 \times 3 = 12$

Now, we calculate the number of times each term is said up to 60.

1. Total times 'idli' is said (Multiples of 4):

Count = $\frac{60}{4} = 15$

2. Total times 'vada' is said (Multiples of 6):

Count = $\frac{60}{6} = 10$

3. Times 'idli-vada' is said (Multiples of 12):

Count = $\frac{60}{12} = 5$

For the Venn diagram figure, we find the counts for the exclusive regions:

- Only 'idli' (Multiples of 4 but not 6): $15 - 5 = 10$

- Only 'vada' (Multiples of 6 but not 4): $10 - 5 = 5$

- 'Idli-vada' (Multiples of 12): $5$

The figure for this game would have:

Intext Question (Page 109)

Question: Which of the following could be the other number:

2, 3, 5, 8, 10?

Answer:

Given:

The ‘idli-vada’ game was played with two numbers. The rules are:

- ‘Idli’ is said for multiples of the smaller number.

- ‘Vada’ is said for multiples of the larger number.

- ‘Idli-vada’ is said for their common multiples.

We have two main clues from the conversation:

1. One of the numbers is 4.

2. The players only said ‘idli’ or ‘idli-vada’. Nobody said just ‘vada’.

To Find:

Which of the numbers from the list {2, 3, 5, 8, 10} could be the other number.

Solution:

The most important clue is that “nobody said just ‘vada’”.

The word 'vada' is said for multiples of the larger number. Saying "just 'vada'" would mean encountering a number that is a multiple of the larger number but not a multiple of the smaller number.

Since this never happened, it means that every time they encountered a multiple of the larger number, it was also a multiple of the smaller number.

This leads to a key conclusion: Every multiple of the larger number must also be a multiple of the smaller number.

This condition can only be true if the larger number is a multiple of the smaller number.

Let the unknown number be $N$. We will test the options by considering two cases:

Case 1: 4 is the smaller number.

If 4 is the smaller number, then the other number $N$ must be larger than 4. From the list, the possible options are {5, 8, 10}.

In this case, the larger number ($N$) must be a multiple of the smaller number (4).

- Is 5 a multiple of 4? No.

- Is 8 a multiple of 4? Yes, because $8 = 2 \times 4$.

- Is 10 a multiple of 4? No.

So, if 4 is the smaller number, the other number could be 8.

Case 2: 4 is the larger number.

If 4 is the larger number, then the other number $N$ must be smaller than 4. From the list, the possible options are {2, 3}.

In this case, the larger number (4) must be a multiple of the smaller number ($N$). This means $N$ must be a factor of 4.

- Is 4 a multiple of 2? Yes, because $4 = 2 \times 2$. (2 is a factor of 4).

- Is 4 a multiple of 3? No.

So, if 4 is the larger number, the other number could be 2.

Combining the results from both cases, the other number could be either 2 or 8.

Therefore, from the given list, the other number could be 2 or 8.

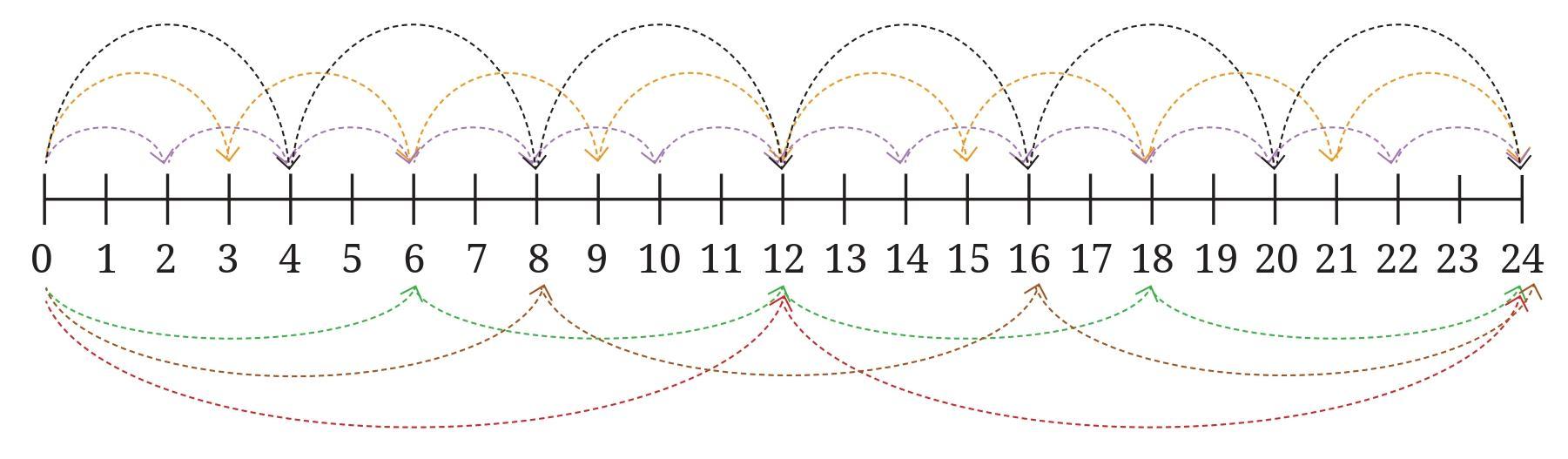

Intext Question (Page 110)

Jump Jackpot

Jumpy and Grumpy play a game.

- Grumpy places a treasure on some number. For example, he may place it on 24.

- Jumpy chooses a jump size. If he chooses 4, then he has to jump only on multiples of 4, starting at 0.

- Jumpy gets the treasure if he lands on the number where Grumpy placed it.

Question: What jump size can reach both 15 and 30? There are multiple jump sizes possible. Try to find them all.

Answer:

Given:

Jumpy plays a game where he starts at 0 and makes jumps of a fixed size. He only lands on multiples of his chosen jump size.

The treasure is placed at two locations: 15 and 30.

To Find:

All possible jump sizes that will allow Jumpy to land on both 15 and 30.

Solution:

For Jumpy to land on a specific number, that number must be a multiple of his jump size. This is equivalent to saying that the jump size must be a factor of the number where the treasure is placed.

In this problem, Jumpy needs to land on both 15 and 30. Therefore, the jump size must be a factor of 15 and also a factor of 30. This means we need to find all the common factors of 15 and 30.

Step 1: Find all the factors of 15.

The numbers that divide 15 without a remainder are its factors.

$1 \times 15 = 15$

$3 \times 5 = 15$

The factors of 15 are {1, 3, 5, 15}.

Step 2: Find all the factors of 30.

The numbers that divide 30 without a remainder are its factors.

$1 \times 30 = 30$

$2 \times 15 = 30$

$3 \times 10 = 30$

$5 \times 6 = 30$

The factors of 30 are {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, 30}.

Step 3: Identify the common factors of 15 and 30.

We look for the numbers that appear in both lists of factors.

Factors of 15: {1, 3, 5, 15}

Factors of 30: {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, 30}

The common factors are 1, 3, 5, and 15.

These are all the possible jump sizes that will allow Jumpy to land on both 15 and 30.

Therefore, the possible jump sizes are 1, 3, 5, and 15.

Intext Question (Page 110)

Question: Look at the table below. What do you notice?

In the table,

1. Is there anything common among the shaded numbers?

2. Is there anything common among the circled numbers?

3. Which numbers are both shaded and circled? What are these numbers called?

Answer:

Upon observing the given table, we can identify distinct patterns for the shaded numbers, the circled numbers, and the numbers that have both properties.

1. Is there anything common among the shaded numbers?

Yes, there is a common property among the numbers in the shaded (green) boxes.

The shaded numbers are: 33, 36, 39, 42, 45, 48, 51, 54, 57, 60, 63, 66, and 69.

If we examine these numbers, we find that each one is divisible by 3.

- $33 = 3 \times 11$

- $36 = 3 \times 12$

- $39 = 3 \times 13$

- $42 = 3 \times 14$

- $45 = 3 \times 15$

- $48 = 3 \times 16$

- $51 = 3 \times 17$

- $54 = 3 \times 18$

- $57 = 3 \times 19$

- $60 = 3 \times 20$

- $63 = 3 \times 21$

- $66 = 3 \times 22$

- $69 = 3 \times 23$

The common property is that all the shaded numbers are multiples of 3.

2. Is there anything common among the circled numbers?

Yes, there is a common property among the circled numbers.

The circled numbers are: 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 56, 60, 64, and 68.

If we examine these numbers, we find that each one is divisible by 4.

- $32 = 4 \times 8$

- $36 = 4 \times 9$

- $40 = 4 \times 10$

- $44 = 4 \times 11$

- $48 = 4 \times 12$

- $52 = 4 \times 13$

- $56 = 4 \times 14$

- $60 = 4 \times 15$

- $64 = 4 \times 16$

- $68 = 4 \times 17$

The common property is that all the circled numbers are multiples of 4.

3. Which numbers are both shaded and circled? What are these numbers called?

By observing the table, we can find the numbers that are inside a green shaded box and also have a circle around them.

The numbers that are both shaded and circled are: 36, 48, and 60.

These numbers possess the properties of both groups:

- They are multiples of 3 (because they are shaded).

- They are also multiples of 4 (because they are circled).

Numbers that are multiples of two or more given numbers are called their common multiples.

Therefore, 36, 48, and 60 are the common multiples of 3 and 4 that appear in the table.

Figure it Out (Page 110 - 111)

Question 1. Find all multiples of 40 that lie between 310 and 410.

Answer:

A "multiple of 40" is just a number you get by multiplying 40 by another whole number. It's like the 40-times table!

We need to find the numbers in the 40-times table that are bigger than 310 but smaller than 410.

Let's start multiplying 40 by different numbers to see what we get.

$40 \times 7 = 280$ (This is too small, it's not bigger than 310.)

$40 \times 8 = 320$ (This is bigger than 310 and smaller than 410. So, 320 is one of our answers!)

$40 \times 9 = 360$ (This one is also between 310 and 410. So, 360 is another answer.)

$40 \times 10 = 400$ (This one works too! 400 is our third answer.)

$40 \times 11 = 440$ (This is too big, it's not smaller than 410.)

So, we stop here. The numbers we found are 320, 360, and 400.

The multiples of 40 that lie between 310 and 410 are 320, 360, and 400.

Question 2. Who am I?

a. I am a number less than 40. One of my factors is 7. The sum of my digits is 8.

b. I am a number less than 100. Two of my factors are 3 and 5. One of my digits is 1 more than the other.

Answer:

Let's solve these number riddles step-by-step!

a. I am a number less than 40. One of my factors is 7. The sum of my digits is 8.

Clue 1: The number is in the 7-times table (because 7 is a factor) and it's less than 40.

Let's list the numbers from the 7-times table that are less than 40:

7, 14, 21, 28, 35

Clue 2: The sum of the number's digits is 8.

Let's check the numbers in our list:

- For 7, the sum is just 7. (Nope)

- For 14, the sum is $1 + 4 = 5$. (Nope)

- For 21, the sum is $2 + 1 = 3$. (Nope)

- For 28, the sum is $2 + 8 = 10$. (Nope)

- For 35, the sum is $3 + 5 = 8$. (Yes! This is our number!)

So, the number is 35.

b. I am a number less than 100. Two of my factors are 3 and 5. One of my digits is 1 more than the other.

Clue 1: The number has both 3 and 5 as factors. This means it can be divided by both 3 and 5. Numbers that can be divided by both 3 and 5 are multiples of 15 (because $3 \times 5 = 15$).

Let's list the multiples of 15 that are less than 100:

15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90

Clue 2: One of its digits is 1 more than the other digit.

Let's check the numbers in our list:

- For 15, the digits are 1 and 5. The difference is 4. (Nope)

- For 30, the digits are 3 and 0. The difference is 3. (Nope)

- For 45, the digits are 4 and 5. The difference is 1. (Yes! This is our number!)

- For 60, the digits are 6 and 0. The difference is 6. (Nope)

- For 75, the digits are 7 and 5. The difference is 2. (Nope)

- For 90, the digits are 9 and 0. The difference is 9. (Nope)

So, the number is 45.

Question 3. A number for which the sum of all its factors is equal to twice the number is called a perfect number. The number 28 is a perfect number. Its factors are 1, 2, 4, 7, 14 and 28. Their sum is 56 which is twice 28. Find a perfect number between 1 and 10.

Answer:

A perfect number is a special number where if you find all of its factors and add them up, the total is exactly double the number you started with.

We need to find a perfect number between 1 and 10. Let's test each number one by one!

Test Number 2:

Factors of 2 are: 1, 2. Sum of factors = $1 + 2 = 3$.

Twice the number = $2 \times 2 = 4$. (3 is not 4, so 2 is not a perfect number).

Test Number 3:

Factors of 3 are: 1, 3. Sum of factors = $1 + 3 = 4$.

Twice the number = $2 \times 3 = 6$. (4 is not 6, so 3 is not a perfect number).

Test Number 4:

Factors of 4 are: 1, 2, 4. Sum of factors = $1 + 2 + 4 = 7$.

Twice the number = $2 \times 4 = 8$. (7 is not 8, so 4 is not a perfect number).

Test Number 5:

Factors of 5 are: 1, 5. Sum of factors = $1 + 5 = 6$.

Twice the number = $2 \times 5 = 10$. (6 is not 10, so 5 is not a perfect number).

Test Number 6:

Factors of 6 are: 1, 2, 3, 6. Sum of factors = $1 + 2 + 3 + 6 = 12$.

Twice the number = $2 \times 6 = 12$. (The sum and twice the number are the same!)

So, 6 is a perfect number!

We have found our answer. The perfect number between 1 and 10 is 6.

Question 4. Find the common factors of:

a. 20 and 28

b. 35 and 50

c. 4, 8 and 12

d. 5, 15 and 25

Answer:

To find the "common factors," we first find all the factors for each number. Then, we look for the factors that are on all the lists. Those are the common ones!

a. Common factors of 20 and 28

Factors of 20 are: 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 20

Factors of 28 are: 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28

The factors they have in common are 1, 2, and 4.

b. Common factors of 35 and 50

Factors of 35 are: 1, 5, 7, 35

Factors of 50 are: 1, 2, 5, 10, 25, 50

The factors they have in common are 1 and 5.

c. Common factors of 4, 8 and 12

Factors of 4 are: 1, 2, 4

Factors of 8 are: 1, 2, 4, 8

Factors of 12 are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12

The factors all three numbers have in common are 1, 2, and 4.

d. Common factors of 5, 15 and 25

Factors of 5 are: 1, 5

Factors of 15 are: 1, 3, 5, 15

Factors of 25 are: 1, 5, 25

The factors all three numbers have in common are 1 and 5.

Question 5. Find any three numbers that are multiples of 25 but not multiples of 50.

Answer:

We are looking for numbers that are in the 25-times table but are NOT in the 50-times table.

First, let's write down some numbers from the 25-times table. We get these by counting by 25s.

25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, ...

Next, let's write down some numbers from the 50-times table. We get these by counting by 50s.

50, 100, 150, 200, ...

Now, we need to pick numbers that are in our first list (multiples of 25) but are NOT in our second list (multiples of 50).

Let's look at the list of multiples of 25 and cross out the ones that are also multiples of 50:

25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, ...

The numbers left are the ones we are looking for!

We can pick any three of these numbers.

Three such numbers are 25, 75, and 125.

(You might notice a pattern: the numbers we picked are made by multiplying 25 by an odd number, like $25 \times 1$, $25 \times 3$, and $25 \times 5$.)

Question 6. Anshu and his friends play the ‘idli-vada’ game with two numbers, which are both smaller than 10. The first time anybody says ‘idlivada’ is after the number 50. What could the two numbers be which are assigned ‘idli’ and ‘vada’?

Answer:

Let's break down this problem.

Clue 1: The two numbers are smaller than 10. So, the numbers could be 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9.

Clue 2: 'Idli-vada' is said for common multiples. The "first time" it is said is for the smallest common multiple, which is the LCM (Least Common Multiple).

Clue 3: The first time they say 'idli-vada' is after the number 50. This means the LCM of the two numbers must be bigger than 50.

Our job is to find pairs of numbers (both smaller than 10) whose LCM is greater than 50.

Let's try some pairs, starting with the biggest numbers since they will give us a big LCM.

- Try 9 and 8:

Multiples of 9: 9, 18, 27, 36, 45, 54, 63, 72, ...

Multiples of 8: 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72, ...

The LCM of 9 and 8 is 72. Since 72 is greater than 50, the pair (9 and 8) could be the two numbers.

- Try 9 and 7:

The LCM of 9 and 7 is $9 \times 7 = 63$. Since 63 is greater than 50, the pair (9 and 7) is another possible answer.

- Try 8 and 7:

The LCM of 8 and 7 is $8 \times 7 = 56$. Since 56 is greater than 50, the pair (8 and 7) is also a possible answer.

- Try 9 and 6:

The LCM of 9 and 6 is 18. This is not greater than 50, so this pair doesn't work.

We have found three possible pairs of numbers.

The two numbers could be 9 and 8, or 9 and 7, or 8 and 7. (Any one of these pairs is a correct answer).

Question 7. In the treasure hunting game, Grumpy has kept treasures on 28 and 70. What jump sizes will land on both the numbers?

Answer:

To find a jump size that lands on both 28 and 70, the jump size must be able to divide both 28 and 70 exactly. In other words, we are looking for the common factors of 28 and 70.

Step 1: Find all the factors of 28.

We think of all the pairs of numbers that multiply to make 28.

$1 \times 28 = 28$

$2 \times 14 = 28$

$4 \times 7 = 28$

The factors of 28 are: 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28.

Step 2: Find all the factors of 70.

We think of all the pairs of numbers that multiply to make 70.

$1 \times 70 = 70$

$2 \times 35 = 70$

$5 \times 14 = 70$

$7 \times 10 = 70$

The factors of 70 are: 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 35, 70.

Step 3: Find the factors that are common to both lists.

Factors of 28: 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28

Factors of 70: 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 35, 70

The numbers that are in both lists are 1, 2, 7, and 14.

These are the jump sizes that will land on both treasures!

The possible jump sizes are 1, 2, 7, and 14.

Answer:

Given:

A Venn diagram showing two circles. The overlapping part, which represents the "Common multiples," contains the numbers 24, 48, and 72.

To Find:

1. The two numbers whose multiples are being shown in the circles.

2. The other numbers that belong in the empty parts of the circles.

Solution:

Step 1: Find the secret of the common multiples.

The common multiples shown are 24, 48, and 72. The smallest of these is 24. Notice that the other common multiples are also in the 24-times table:

- $48 = 2 \times 24$

- $72 = 3 \times 24$

This tells us that the smallest common multiple, or the LCM (Least Common Multiple), of the two unknown numbers is 24.

Step 2: Find the two unknown numbers.

We need to find two numbers that have 24 as their LCM. This means both numbers must be factors of 24. Let's list the factors of 24:

Factors of 24 are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24.

Now we can pick a pair of these factors and check if their LCM is 24. There are several possible pairs, but let's choose one good example: 6 and 8.

Let's check the LCM of 6 and 8:

Multiples of 6: 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, ...

Multiples of 8: 8, 16, 24, 32, ...

The LCM is indeed 24. So, the two numbers could be 6 and 8.

So, the Red Circle represents Multiples of 6 and the Green Circle represents Multiples of 8.

Step 3: Fill in the missing numbers.

Let's find the multiples of 6 and 8 up to 72 (the largest number in the diagram) and place them in the correct parts of the circles.

Red Circle (Multiples of 6): 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, 60, 66, 72.

Green Circle (Multiples of 8): 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72.

The numbers that are in both lists (24, 48, 72) stay in the middle. The other numbers go into the parts of the circles that do not overlap.

- Numbers in the Red Circle ONLY (Multiples of 6 but not 8): 6, 12, 18, 30, 36, 42, 54, 60, 66.

- Numbers in the Green Circle ONLY (Multiples of 8 but not 6): 8, 16, 32, 40, 56, 64.

Final Answer:

The two numbers are 6 and 8. Here is the completed diagram:

Note: Other pairs of numbers could also work, such as (3 and 8) or (8 and 12). Each pair would give different numbers in the empty regions.

Question 9. Find the smallest number that is a multiple of all the numbers from 1 to 10 except for 7.

Answer:

We are looking for the smallest number that can be divided evenly by all of these numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10.

This "smallest number" is called the Least Common Multiple (LCM) of that group of numbers.

To find the LCM, we can use the prime factorization method. This means we break down each number into a product of its prime factors.

- $1 = 1$ (We can ignore 1)

- $2 = 2$

- $3 = 3$

- $4 = 2 \times 2$

- $5 = 5$

- $6 = 2 \times 3$

- $8 = 2 \times 2 \times 2$

- $9 = 3 \times 3$

- $10 = 2 \times 5$

Now, let's build our LCM. We need to make a number that has all these prime factors in it. We look at each prime number (2, 3, 5) and find the most times it appears in any single breakdown.

- For the prime factor 2: The number 8 has the most 2s. It has three 2s ($2 \times 2 \times 2$). So, we need three 2s in our LCM.

- For the prime factor 3: The number 9 has the most 3s. It has two 3s ($3 \times 3$). So, we need two 3s in our LCM.

- For the prime factor 5: The number 5 (and 10) has one 5. So, we need one 5 in our LCM.

To get the LCM, we multiply these chosen factors together:

LCM = $\underbrace{(2 \times 2 \times 2)}_{\text{from 8}} \times \underbrace{(3 \times 3)}_{\text{from 9}} \times \underbrace{(5)}_{\text{from 5}}$

$= 8 \times 9 \times 5$

$= 72 \times 5$

$= 360$

The smallest number is 360.

Question 10. Find the smallest number that is a multiple of all the numbers from 1 to 10.

Answer:

We need to find the smallest number that can be divided by every number from 1 to 10 without leaving a remainder. This number is the Least Common Multiple (LCM) of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

We can find this by using prime factorization. Let's break down each number into its prime factors.

- $1 = 1$

- $2 = 2$

- $3 = 3$

- $4 = 2 \times 2$

- $5 = 5$

- $6 = 2 \times 3$

- $7 = 7$

- $8 = 2 \times 2 \times 2$

- $9 = 3 \times 3$

- $10 = 2 \times 5$

To build the LCM, we will take the highest number of each prime factor we see in any of the breakdowns.

- For the prime factor 2: The number 8 has the most 2s ($2 \times 2 \times 2$). We need three 2s.

- For the prime factor 3: The number 9 has the most 3s ($3 \times 3$). We need two 3s.

- For the prime factor 5: The number 5 has one 5. We need one 5.

- For the prime factor 7: The number 7 has one 7. We need one 7.

Now, let's multiply all these prime factors together to get our LCM.

LCM = $(2 \times 2 \times 2) \times (3 \times 3) \times 5 \times 7$

$= 8 \times 9 \times 5 \times 7$

$= 72 \times 35$

$= 2520$

The smallest number that is a multiple of all numbers from 1 to 10 is 2520.

Intext Question (Page 113)

Question: How many prime numbers are there from 21 to 30? How many composite numbers are there from 21 to 30?

Answer:

To Find:

1. The number of prime numbers between 21 and 30.

2. The number of composite numbers between 21 and 30.

Solution:

First, let's quickly review the definitions:

- A Prime Number is a whole number greater than 1 that has exactly two factors: 1 and itself.

- A Composite Number is a whole number greater than 1 that has more than two factors.

Now, let's examine each number in the range from 21 to 30 to see which type it is.

| Number | Factors | Type (Prime/Composite) |

| 21 | 1, 3, 7, 21 (since $3 \times 7 = 21$) | Composite |

| 22 | 1, 2, 11, 22 (since $2 \times 11 = 22$) | Composite |

| 23 | 1, 23 (has only two factors) | Prime |

| 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 | Composite |

| 25 | 1, 5, 25 (since $5 \times 5 = 25$) | Composite |

| 26 | 1, 2, 13, 26 (since $2 \times 13 = 26$) | Composite |

| 27 | 1, 3, 9, 27 (since $3 \times 9 = 27$) | Composite |

| 28 | 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28 | Composite |

| 29 | 1, 29 (has only two factors) | Prime |

| 30 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, 30 | Composite |

Counting the Prime Numbers:

From the table above, the only prime numbers between 21 and 30 are 23 and 29.

Therefore, there are 2 prime numbers from 21 to 30.

Counting the Composite Numbers:

The composite numbers between 21 and 30 are 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, and 30.

Therefore, there are 8 composite numbers from 21 to 30.

Figure it Out (Page 114 - 115)

Question 1. We see that 2 is a prime and also an even number. Is there any other even prime?

Answer:

No, the number 2 is the one and only even prime number.

Detailed Explanation:

To understand why this is true, let's first review the definitions of "even" and "prime".

- An Even Number is a whole number that is a multiple of 2. This means it can be divided by 2 with no remainder.

- A Prime Number is a whole number greater than 1 that has exactly two factors (divisors): 1 and itself.

The Logic:

1. Why is 2 a prime number?

The number 2 is even. Its factors are only 1 and 2. Since it has exactly two factors, it perfectly fits the definition of a prime number.

2. Why can't any other even number be prime?

Let's take any other even number, for example, 4, 6, 8, 12, or 100.

By the very definition of an even number, we know that 2 is a factor of that number.

So, for any even number greater than 2, its list of factors will always include:

- 1 (which is a factor of every number)

- 2 (because the number is even)

- The number itself

Since any even number greater than 2 has at least three factors (1, 2, and itself), it has more than the two factors allowed for a prime number. This means every even number greater than 2 is a composite number.

Conclusion:

The number 2 is unique. It is the only even number that has exactly two factors (1 and 2). Every other even number has 2 as a factor in addition to 1 and itself, making them composite. Therefore, 2 is the only even prime number.

Question 2. Look at the list of primes till 100. What is the smallest difference between two successive primes? What is the largest difference?

Answer:

To Find:

1. The smallest difference between two consecutive prime numbers up to 100.

2. The largest difference between two consecutive prime numbers up to 100.

Solution:

First, we need to list all the prime numbers from 1 to 100. By looking at the circled numbers in the Sieve of Eratosthenes chart, the prime numbers are:

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97.

Next, we will find the difference between each prime number and the one immediately following it (successive primes).

| Successive Primes | Difference | Successive Primes | Difference |

| $3 - 2$ | 1 | $59 - 53$ | 6 |

| $5 - 3$ | 2 | $61 - 59$ | 2 |

| $7 - 5$ | 2 | $67 - 61$ | 6 |

| $11 - 7$ | 4 | $71 - 67$ | 4 |

| $13 - 11$ | 2 | $73 - 71$ | 2 |

| $17 - 13$ | 4 | $79 - 73$ | 6 |

| $19 - 17$ | 2 | $83 - 79$ | 4 |

| $23 - 19$ | 4 | $89 - 83$ | 6 |

| $29 - 23$ | 6 | $97 - 89$ | 8 |

| $31 - 29$ | 2 | ||

| $37 - 31$ | 6 | ||

| $41 - 37$ | 4 | ||

| $43 - 41$ | 2 | ||

| $47 - 43$ | 4 | ||

| $53 - 47$ | 6 |

After calculating all the differences, we can now find the smallest and largest values.

Smallest Difference:

By looking at the table, the smallest difference is 1, which is between the prime numbers 2 and 3.

Largest Difference:

By looking at the table, the largest difference is 8, which is between the prime numbers 89 and 97.

Question 3. Are there an equal number of primes occurring in every row in the table on the previous page? Which decades have the least number of primes? Which have the most number of primes?

Answer:

To answer this, we need to count the prime numbers in each row (or "decade") of the number chart from 1 to 100.

Here is a count of the prime numbers in each row:

| Decade (Row) | Prime Numbers in this Decade | Count |

| 1-10 | 2, 3, 5, 7 | 4 |

| 11-20 | 11, 13, 17, 19 | 4 |

| 21-30 | 23, 29 | 2 |

| 31-40 | 31, 37 | 2 |

| 41-50 | 41, 43, 47 | 3 |

| 51-60 | 53, 59 | 2 |

| 61-70 | 61, 67 | 2 |

| 71-80 | 71, 73, 79 | 3 |

| 81-90 | 83, 89 | 2 |

| 91-100 | 97 | 1 |

1. Are there an equal number of primes in every row?

No. As you can see from the table, the number of primes changes from row to row. The first row has 4 primes, but the last row only has 1.

2. Which decades have the least number of primes?

Looking at the "Count" column, the smallest number is 1.

The decade with the least number of primes is 91-100, with only one prime number (97).

3. Which decades have the most number of primes?

Looking at the "Count" column, the largest number is 4.

The decades with the most number of primes are 1-10 and 11-20, which both have four prime numbers.

Question 4. Which of the following numbers are prime? 23, 51, 37, 26

Answer:

A prime number is a whole number bigger than 1 that can only be divided by 1 and itself. A number that has other factors is called a composite number.

Let's check each number:

- 23: Can you think of any numbers that multiply to make 23, other than $1 \times 23$? No. So, 23 is prime.

- 51: Let's test if it can be divided by small prime numbers. For 3, we can add its digits: $5 + 1 = 6$. Since 6 is divisible by 3, 51 is also divisible by 3 ($51 = 3 \times 17$). Because it has factors other than 1 and 51, 51 is composite (not prime).

- 37: Can you think of any numbers that multiply to make 37, other than $1 \times 37$? No. So, 37 is prime.

- 26: This is an even number, so it can be divided by 2 ($26 = 2 \times 13$). Because it has factors other than 1 and 26, 26 is composite (not prime).

The prime numbers from the list are 23 and 37.

Question 5. Write three pairs of prime numbers less than 20 whose sum is a multiple of 5.

Answer:

Let's solve this in three steps.

Step 1: List all the prime numbers less than 20.

The prime numbers are: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19.

Step 2: Find pairs from this list that add up to a multiple of 5.

A multiple of 5 is a number from the 5-times table (like 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, ...). A quick trick is to look for sums that end in a 0 or a 5.

- $2 + 3 = 5$ (5 is a multiple of 5)

- $3 + 7 = 10$ (10 is a multiple of 5)

- $2 + 13 = 15$ (15 is a multiple of 5)

- $3 + 17 = 20$ (20 is a multiple of 5)

- $7 + 13 = 20$ (20 is a multiple of 5)

- $13 + 17 = 30$ (30 is a multiple of 5)

Step 3: Write down any three of these pairs.

Here are three possible answers:

1. (2, 3) because $2 + 3 = 5$

2. (3, 7) because $3 + 7 = 10$

3. (13, 17) because $13 + 17 = 30$

Question 6. The numbers 13 and 31 are prime numbers. Both these numbers have same digits 1 and 3. Find such pairs of prime numbers up to 100.

Answer:

We are looking for pairs of prime numbers where one number is the reverse of the other. These are sometimes called emirps (prime spelled backward).

Step 1: List all the prime numbers up to 100.

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97.

Step 2: Check each two-digit prime number from the list.

We will take each two-digit prime, reverse its digits, and see if the new number is also on our prime number list.

- 13: Reverse is 31. Is 31 prime? Yes. So, (13, 31) is a pair. (This was in the question).

- 17: Reverse is 71. Is 71 prime? Yes. So, (17, 71) is a pair.

- 19: Reverse is 91. Is 91 prime? No, $91 = 7 \times 13$.

- 37: Reverse is 73. Is 73 prime? Yes. So, (37, 73) is a pair.

- 79: Reverse is 97. Is 97 prime? Yes. So, (79, 97) is a pair.

Let's check a few more just to be sure. If we take 23, the reverse is 32, which is not prime. If we take 41, the reverse is 14, which is not prime. A prime number cannot end in 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, or 0 (unless it is the number 2 or 5 itself). This helps us quickly eliminate many possibilities.

The pairs of prime numbers up to 100 that have the same digits are:

- 13 and 31

- 17 and 71

- 37 and 73

- 79 and 97

Question 7. Find seven consecutive composite numbers between 1 and 100.

Answer:

A composite number is a whole number that has more factors than just 1 and itself. For example, 10 is composite because its factors are 1, 2, 5, and 10.

We need to find a streak of seven numbers in a row that are all composite.

To find a long streak of composite numbers, it's a good idea to look for a big gap between two prime numbers.

Let's look at the prime numbers near the end of the 1-100 range:

... 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97 ...

There is a gap between 89 and 97. Let's check all the numbers in between them:

90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96

This is a list of seven consecutive numbers. Now let's check if they are all composite.

- 90 is composite (it ends in 0, so it's divisible by 10).

- 91 is composite (it's divisible by 7, $91 = 7 \times 13$).

- 92 is composite (it's an even number).

- 93 is composite (its digits add to 12, so it's divisible by 3).

- 94 is composite (it's an even number).

- 95 is composite (it ends in 5, so it's divisible by 5).

- 96 is composite (it's an even number).

All seven of these numbers are composite!

The seven consecutive composite numbers are 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, and 96.

Question 8. Twin primes are pairs of primes having a difference of 2. For example, 3 and 5 are twin primes. So are 17 and 19. Find the other twin primes between 1 and 100.

Answer:

Twin primes are a special pair of prime numbers that are very close together – they have a difference of exactly 2.

Step 1: List all the prime numbers between 1 and 100.

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97.

Step 2: Look for pairs in the list that are 2 apart.

Let's go through the list and check:

- (3, 5) → $5 - 3 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (5, 7) → $7 - 5 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (11, 13) → $13 - 11 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (17, 19) → $19 - 17 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (29, 31) → $31 - 29 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (41, 43) → $43 - 41 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (59, 61) → $61 - 59 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

- (71, 73) → $73 - 71 = 2$. Yes, this is a pair.

The other pairs, like (7, 11) have a difference of 4, so they are not twin primes.

The twin prime pairs between 1 and 100 are:

(3, 5), (5, 7), (11, 13), (17, 19), (29, 31), (41, 43), (59, 61), (71, 73).

Question 9. Identify whether each statement is true or false. Explain.

a. There is no prime number whose units digit is 4.

b. A product of primes can also be prime.

c. Prime numbers do not have any factors.

d. All even numbers are composite numbers.

e. 2 is a prime and so is the next number, 3. For every other prime, the next number is composite.

Answer:

a. There is no prime number whose units digit is 4.

True. Any number that ends in 4 is an even number (like 14, 24, 34). All even numbers greater than 2 can be divided by 2, which means they have more than two factors and are composite. So, no prime number can end in 4.

b. A product of primes can also be prime.

False. When you multiply two or more prime numbers together, the result is a new number that has the original primes as its factors. For example, $2 \times 3 = 6$. The factors of 6 are 1, 2, 3, and 6. Since it has more than two factors, it is composite, not prime.

c. Prime numbers do not have any factors.

False. This is the opposite of the definition! Every prime number has exactly two factors: 1 and itself. For example, the factors of 7 are 1 and 7.

d. All even numbers are composite numbers.

False. There is one exception: the number 2. The number 2 is even, but its only factors are 1 and 2, which makes it a prime number.

e. 2 is a prime and so is the next number, 3. For every other prime, the next number is composite.

True. After 3, every other prime number is odd (like 5, 7, 11, etc.). The number that comes right after any odd number is always an even number. Since all even numbers greater than 2 are composite, the number after any prime (except 2) will be an even, composite number.

Question 10. Which of the following numbers is the product of exactly three distinct prime numbers: 45, 60, 91, 105, 330?

Answer:

"Distinct" means different. So we are looking for a number that is made by multiplying three different prime numbers together.

We can find this by breaking each number down into its prime factors.

- 45: $45 = 5 \times 9 = 5 \times 3 \times 3$. The prime factors are 3 and 5. This is only two distinct prime numbers.

- 60: $60 = 6 \times 10 = (2 \times 3) \times (2 \times 5) = 2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 5$. The distinct prime factors are 2, 3, and 5. This is exactly three distinct prime numbers. So, 60 is one answer.

- 91: $91 = 7 \times 13$. The prime factors are 7 and 13. This is only two distinct prime numbers.

- 105: $105 = 5 \times 21 = 5 \times 3 \times 7$. The distinct prime factors are 3, 5, and 7. This is exactly three distinct prime numbers. So, 105 is another answer.

- 330: $330 = 10 \times 33 = (2 \times 5) \times (3 \times 11)$. The distinct prime factors are 2, 3, 5, and 11. This is four distinct prime numbers.

The numbers that are the product of exactly three distinct prime numbers are 60 and 105.

Question 11. How many three-digit prime numbers can you make using each of 2, 4 and 5 once?

Answer:

Let's think about the numbers we can make using the digits 2, 4, and 5.

The possible three-digit numbers are:

245, 254, 425, 452, 524, 542

Now, let's see if any of these can be prime. We can use some simple divisibility rules to check.

- A number is divisible by 2 if it ends in an even digit (0, 2, 4, 6, 8).

- A number is divisible by 5 if it ends in a 0 or a 5.

Let's check our list:

- Numbers ending in 4 or 2: 254, 452, 524, 542. All of these are even numbers, so they can be divided by 2. This means they are not prime.

- Numbers ending in 5: 245, 425. Both of these can be divided by 5. This means they are not prime.

Every single number we can make is divisible by either 2 or 5. Since none of them can be prime, the answer is zero.

You can make 0 (zero) prime numbers using the digits 2, 4, and 5.

Question 12. Observe that 3 is a prime number, and 2 × 3 + 1 = 7 is also a prime. Are there other primes for which doubling and adding 1 gives another prime? Find at least five such examples.

Answer:

Yes, there are other prime numbers that follow this pattern!

We are looking for a prime number (let's call it 'p') where if we calculate $2 \times p + 1$, the answer is also a prime number.

Let's test some prime numbers to find five examples.

1. Test p = 2 (2 is prime)

$2 \times 2 + 1 = 4 + 1 = 5$. Is 5 prime? Yes. So, 2 is an example.

2. Test p = 3 (3 is prime)

$2 \times 3 + 1 = 6 + 1 = 7$. Is 7 prime? Yes. So, 3 is an example (from the question).

3. Test p = 5 (5 is prime)

$2 \times 5 + 1 = 10 + 1 = 11$. Is 11 prime? Yes. So, 5 is an example.

4. Test p = 7 (7 is prime)

$2 \times 7 + 1 = 14 + 1 = 15$. Is 15 prime? No ($15 = 3 \times 5$). So, 7 is not an example.

5. Test p = 11 (11 is prime)

$2 \times 11 + 1 = 22 + 1 = 23$. Is 23 prime? Yes. So, 11 is an example.

6. Test p = 13 (13 is prime)

$2 \times 13 + 1 = 26 + 1 = 27$. Is 27 prime? No ($27 = 3 \times 9$). So, 13 is not an example.

7. Test p = 23 (23 is prime)

$2 \times 23 + 1 = 46 + 1 = 47$. Is 47 prime? Yes. So, 23 is an example.

We have found five examples. The prime numbers that work are:

2, 3, 5, 11, and 23.

Intext Question (Page 116)

Question: Which of the following pairs of numbers are co-prime?

a. 18 and 35

b. 15 and 37

c. 30 and 415

d. 17 and 69

e. 81 and 18

Answer:

Two numbers are co-prime if they don't share any common factors other than the number 1. It's like they are "prime" relative to each other.

Let's check each pair by finding their factors.

a. 18 and 35

Factors of 18 are: 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18.

Factors of 35 are: 1, 5, 7, 35.

The only factor they have in common is 1. So, 18 and 35 are co-prime.

b. 15 and 37

Factors of 15 are: 1, 3, 5, 15.

Factors of 37 are: 1, 37 (37 is a prime number).

The only factor they have in common is 1. So, 15 and 37 are co-prime.

c. 30 and 415

Let's look for common factors. Both numbers end in a 0 or a 5, which means they are both divisible by 5.

Since they share a common factor of 5 (which is not 1), 30 and 415 are not co-prime.

d. 17 and 69

Factors of 17 are: 1, 17 (17 is a prime number).

Factors of 69 are: 1, 3, 23, 69.

The only factor they have in common is 1. So, 17 and 69 are co-prime.

e. 81 and 18

Let's look for common factors. The digits of 81 add up to 9 ($8+1=9$), and the digits of 18 add up to 9 ($1+8=9$). This means both numbers are divisible by 3 and by 9.

Since they share common factors of 3 and 9, 81 and 18 are not co-prime.

The pairs of numbers that are co-prime are:

a. 18 and 35

b. 15 and 37

d. 17 and 69

Question: While playing the ‘idli-vada’ game with different number pairs, Anshu observed something interesting!

a. Sometimes the first common multiple was the same as the product of the two numbers.

b. At other times the first common multiple was less than the product of the two numbers.

Find examples for each of the above. How is it related to the number pair being co-prime?

Answer:

Anshu's observation is about the Least Common Multiple (LCM), which is the "first common multiple" in the idli-vada game.

a. The LCM is the SAME as the product of the two numbers.

This happens when the two numbers don't share any common factors other than 1. In other words, this happens when the numbers are co-prime.

Example 1: Numbers 3 and 5

- Product: $3 \times 5 = 15$.

- LCM: The first number to appear in both the 3-times table and the 5-times table is 15.

- The LCM (15) is the same as the product (15). This works because 3 and 5 are co-prime.

Example 2: Numbers 4 and 9

- Product: $4 \times 9 = 36$.

- LCM: The first number to appear in both the 4-times table and the 9-times table is 36.

- The LCM (36) is the same as the product (36). This works because 4 and 9 are co-prime.

b. The LCM is LESS than the product of the two numbers.

This happens when the two numbers share a common factor that is bigger than 1. In other words, this happens when the numbers are not co-prime.

Example 1: Numbers 6 and 8

- Product: $6 \times 8 = 48$.

- LCM: Multiples of 6 are 6, 12, 18, 24... Multiples of 8 are 8, 16, 24... The LCM is 24.

- The LCM (24) is less than the product (48). This is because 6 and 8 are not co-prime (they share a common factor of 2).

Example 2: Numbers 10 and 15

- Product: $10 \times 15 = 150$.

- LCM: The first number to appear in both the 10-times table and the 15-times table is 30.

- The LCM (30) is less than the product (150). This is because 10 and 15 are not co-prime (they share a common factor of 5).

The Relationship with Co-prime Numbers

- If two numbers are co-prime, their LCM is simply their product.

- If two numbers are not co-prime, their LCM will be smaller than their product.

Intext Question (Page 117)

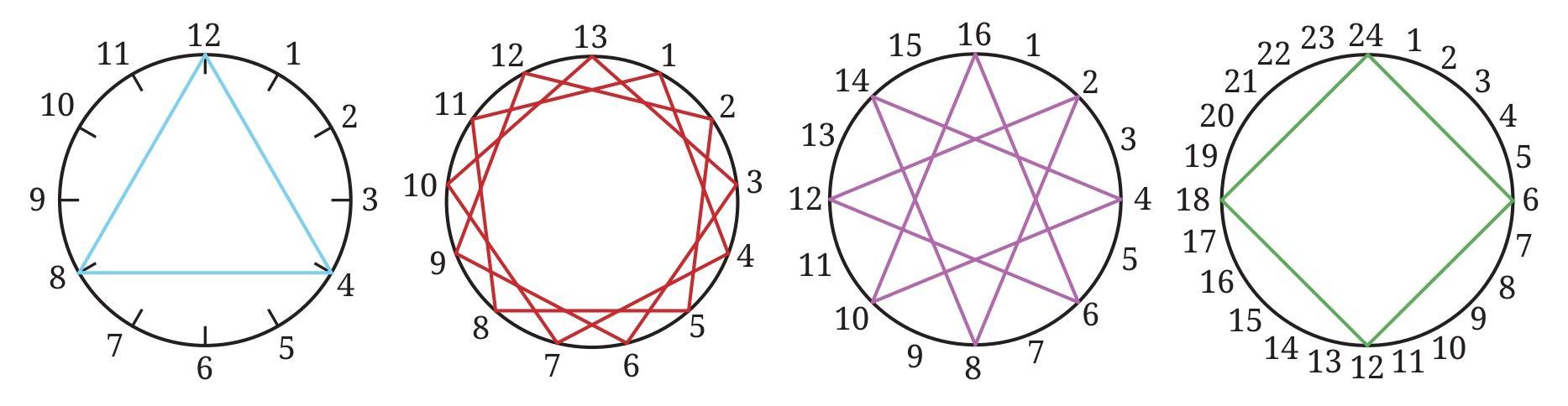

Observe the following thread art. The first diagram has 12 pegs and the thread is tied to every fourth peg (we say that the thread-gap is 4). The second diagram has 13 pegs and the thread-gap is 3. What about the other diagrams? Observe these pictures, share and discuss your findings in class.

In some diagrams, the thread is tied to every peg. In some, it is not. Is it related to the two numbers (the number of pegs and the thread-gap) being co-prime?

Question: Make such pictures for the following:

a. 15 pegs, thread-gap of 10

b. 10 pegs, thread-gap of 7

c. 14 pegs, thread-gap of 6

d. 8 pegs, thread-gap of 3

Answer:

To understand whether the thread will be tied to every peg or not, we need to look at the relationship between the number of pegs ($n$) and the thread-gap ($g$). The thread is tied to every peg only if the two numbers are co-prime (i.e., their Highest Common Factor or HCF is 1).

$\text{HCF}(n, g) = 1$

[Condition for visiting all pegs] ... (i)

If the HCF is greater than 1, the thread will return to the starting peg without visiting all other pegs.

a. 15 pegs, thread-gap of 10

Given: Number of pegs ($n$) = 15, Thread-gap ($g$) = 10.

To Find: Whether the thread visits all pegs and the resulting pattern.

First, we find the prime factorization of both numbers to check if they are co-prime:

For 15:

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 3 & 15 \\ \hline 5 & 5 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$For 10:

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 10 \\ \hline 5 & 5 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$Common factor is 5. Therefore:

$\text{HCF}(15, 10) = 5$

($5 \neq 1$)

Conclusion: Since the HCF is 5, the numbers are not co-prime. The thread will not be tied to every peg. It will only visit $15 \div 5 = 3$ pegs (pegs 10, 5, and 15), forming a triangle.

b. 10 pegs, thread-gap of 7

Given: Number of pegs ($n$) = 10, Thread-gap ($g$) = 7.

To Find: Whether the thread visits all pegs.

We check the HCF of 10 and 7:

$\text{HCF}(10, 7) = 1$

(7 is a prime number and not a factor of 10)

Conclusion: Since the HCF is 1, the numbers are co-prime. According to condition (i), the thread will be tied to every peg. It will form a beautiful 10-pointed star pattern.

c. 14 pegs, thread-gap of 6

Given: Number of pegs ($n$) = 14, Thread-gap ($g$) = 6.

To Find: Whether the thread visits all pegs.

Let's check the common factors:

For 14:

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 14 \\ \hline 7 & 7 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$For 6:

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 6 \\ \hline 3 & 3 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$The common factor is 2. Therefore:

$\text{HCF}(14, 6) = 2$

($2 \neq 1$)

Conclusion: Since the HCF is 2, the numbers are not co-prime. The thread will not be tied to every peg. It will only visit $14 \div 2 = 7$ pegs, forming a heptagon (7-sided figure) inside the circle.

d. 8 pegs, thread-gap of 3

Given: Number of pegs ($n$) = 8, Thread-gap ($g$) = 3.

To Find: Whether the thread visits all pegs.

We check for common factors between 8 and 3:

$\text{HCF}(8, 3) = 1$

(3 is prime and 8 is not a multiple of 3)

Conclusion: Since the HCF is 1, the numbers are co-prime. The thread will be tied to every peg, resulting in an 8-pointed star pattern.

Figure it Out (Page 120)

Question 1. Find the prime factorisations of the following numbers: 64, 104, 105, 243, 320, 141, 1728, 729, 1024, 1331, 1000.

Answer:

To find the prime factorization of a number, we repeatedly divide it by prime numbers until we are left with 1. The prime numbers used as divisors make up the prime factorization.

Prime Factorization of 64

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 64 \\ \hline 2 & 32 \\ \hline 2 & 16 \\ \hline 2 & 8 \\ \hline 2 & 4 \\ \hline 2 & 2 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $64 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 = 2^6$.

Prime Factorization of 104

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 104 \\ \hline 2 & 52 \\ \hline 2 & 26 \\ \hline 13 & 13 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $104 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 13 = 2^3 \times 13$.

Prime Factorization of 105

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 3 & 105 \\ \hline 5 & 35 \\ \hline 7 & 7 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $105 = 3 \times 5 \times 7$.

Prime Factorization of 243

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 3 & 243 \\ \hline 3 & 81 \\ \hline 3 & 27 \\ \hline 3 & 9 \\ \hline 3 & 3 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $243 = 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 = 3^5$.

Prime Factorization of 320

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 320 \\ \hline 2 & 160 \\ \hline 2 & 80 \\ \hline 2 & 40 \\ \hline 2 & 20 \\ \hline 2 & 10 \\ \hline 5 & 5 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $320 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 5 = 2^6 \times 5$.

Prime Factorization of 141

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 3 & 141 \\ \hline 47 & 47 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $141 = 3 \times 47$.

Prime Factorization of 1728

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 1728 \\ \hline 2 & 864 \\ \hline 2 & 432 \\ \hline 2 & 216 \\ \hline 2 & 108 \\ \hline 2 & 54 \\ \hline 3 & 27 \\ \hline 3 & 9 \\ \hline 3 & 3 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $1728 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 = 2^6 \times 3^3$.

Prime Factorization of 729

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 3 & 729 \\ \hline 3 & 243 \\ \hline 3 & 81 \\ \hline 3 & 27 \\ \hline 3 & 9 \\ \hline 3 & 3 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $729 = 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3 = 3^6$.

Prime Factorization of 1024

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 1024 \\ \hline 2 & 512 \\ \hline 2 & 256 \\ \hline 2 & 128 \\ \hline 2 & 64 \\ \hline 2 & 32 \\ \hline 2 & 16 \\ \hline 2 & 8 \\ \hline 2 & 4 \\ \hline 2 & 2 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $1024 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 = 2^{10}$.

Prime Factorization of 1331

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 11 & 1331 \\ \hline 11 & 121 \\ \hline 11 & 11 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $1331 = 11 \times 11 \times 11 = 11^3$.

Prime Factorization of 1000

$\begin{array}{c|cc} 2 & 1000 \\ \hline 2 & 500 \\ \hline 2 & 250 \\ \hline 5 & 125 \\ \hline 5 & 25 \\ \hline 5 & 5 \\ \hline & 1 \end{array}$

So, $1000 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 5 \times 5 \times 5 = 2^3 \times 5^3$.

Question 2. The prime factorisation of a number has one 2, two 3s, and one 11. What is the number?

Answer:

We are given the "recipe" for a number using its prime factors. To find the number, we just need to multiply these ingredients together.

The prime factors are:

- One 2

- Two 3s (which is $3 \times 3$)

- One 11

Let's multiply them all together:

Number = $2 \times (3 \times 3) \times 11$

$= 2 \times 9 \times 11$

$= 18 \times 11$

$= 198$

The number is 198.

Question 3. Find three prime numbers, all less than 30, whose product is 1955.

Answer:

To find the three prime numbers that multiply to make 1955, we need to find the prime factorization of 1955.

Step 1: Start dividing 1955 by small prime numbers.

- The number ends in 5, so it must be divisible by 5.

$1955 \div 5 = 391$

So, $1955 = 5 \times 391$.

Step 2: Now, find the prime factors of 391.

We need to test prime numbers to see if they divide 391. Let's try primes bigger than 5.

- Try 7: $391 \div 7$ leaves a remainder.

- Try 11: $391 \div 11$ leaves a remainder.

- Try 13: $391 \div 13$ leaves a remainder.

- Try 17: $391 \div 17 = 23$. It works!

So, $391 = 17 \times 23$.

Step 3: Put it all together.

The prime factorization of 1955 is $5 \times 17 \times 23$.

Let's check the conditions:

- Are 5, 17, and 23 all prime numbers? Yes.

- Are they all less than 30? Yes.

The three prime numbers are 5, 17, and 23.

Question 4. Find the prime factorisation of these numbers without multiplying first

a. 56 × 25

b. 108 × 75

c. 1000 × 81

Answer:

The trick here is to find the prime factors of each number in the multiplication problem separately, and then just combine all the prime factors into one big list.

a. 56 × 25

Prime factors of 56: $56 = 8 \times 7 = (2 \times 2 \times 2) \times 7$

Prime factors of 25: $25 = 5 \times 5$

Now, combine them: $56 \times 25 = (2 \times 2 \times 2) \times 7 \times (5 \times 5) = \boldsymbol{2^3 \times 5^2 \times 7}$

b. 108 × 75

Prime factors of 108: $108 = 2 \times 54 = 2 \times 2 \times 27 = 2 \times 2 \times \ $$ 3 \times 3 \times 3 = 2^2 \times 3^3$

Prime factors of 75: $75 = 3 \times 25 = 3 \times 5 \times 5 = 3 \times 5^2$

Combine them: $108 \times 75 = (2^2 \times 3^3) \times (3 \times 5^2) = \boldsymbol{2^2 \times 3^4 \times 5^2}$ (We have four 3s in total).

c. 1000 × 81

Prime factors of 1000: $1000 = 10 \times 10 \times 10 = (2 \times 5) \times (2 \times 5) \ $$ \times (2 \times 5) = 2^3 \times 5^3$

Prime factors of 81: $81 = 9 \times 9 = (3 \times 3) \times (3 \times 3) = 3^4$

Combine them: $1000 \times 81 = (2^3 \times 5^3) \times 3^4 = \boldsymbol{2^3 \times 3^4 \times 5^3}$

Question 5. What is the smallest number whose prime factorisation has:

a. three different prime numbers?

b. four different prime numbers?

Answer:

To make the smallest possible number with a certain number of different prime factors, we should always pick the smallest prime numbers.

a. three different prime numbers

The three smallest prime numbers are 2, 3, and 5.

To find the smallest number, we multiply them together:

$2 \times 3 \times 5 = 6 \times 5 = \boldsymbol{30}$

b. four different prime numbers

The four smallest prime numbers are 2, 3, 5, and 7.

To find the smallest number, we multiply them together:

$2 \times 3 \times 5 \times 7 = 30 \times 7 = \boldsymbol{210}$

Figure it Out (Page 122)

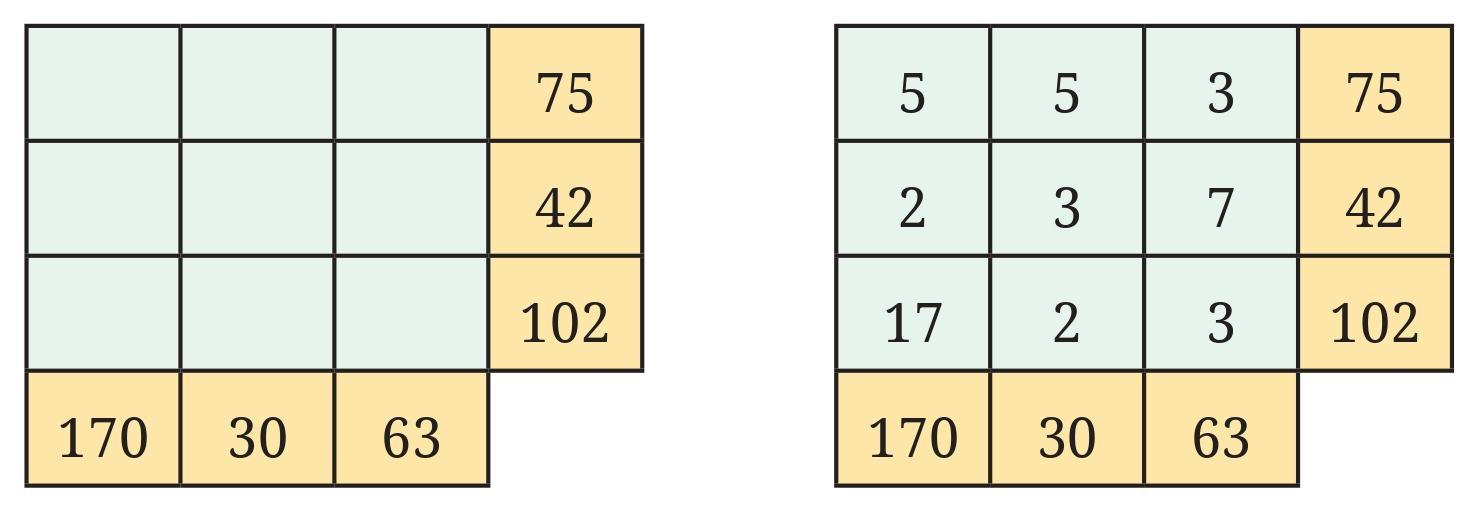

Question 1. Are the following pairs of numbers co-prime? Guess first and then use prime factorisation to verify your answer.

a. 30 and 45

b. 57 and 85

c. 121 and 1331

d. 343 and 216

Answer:

Two numbers are co-prime if they don't share any prime factors. If they do share a prime factor, they are not co-prime.

a. 30 and 45

Guess: Both numbers end in 0 or 5, so they are both in the 5-times table. They are probably not co-prime.

Verification:

Prime factors of 30: $2 \times 3 \times 5$

Prime factors of 45: $3 \times 3 \times 5$

They share the prime factors 3 and 5. Since they have common prime factors, they are not co-prime.

b. 57 and 85

Guess: This is tricky to guess. Let's find their prime factors.

Verification:

Prime factors of 57: $5+7=12$, so it's divisible by 3. $57 = 3 \times 19$.

Prime factors of 85: Ends in 5, so it's divisible by 5. $85 = 5 \times 17$.

The prime factors of 57 are {3, 19}. The prime factors of 85 are {5, 17}. They do not share any prime factors. Therefore, they are co-prime.

c. 121 and 1331

Guess: I recognize these as powers of 11. They probably share 11 as a factor.

Verification:

Prime factors of 121: $11 \times 11$

Prime factors of 1331: $11 \times 11 \times 11$

They share the prime factor 11. Therefore, they are not co-prime.

d. 343 and 216

Guess: These numbers don't look like they share any factors.

Verification:

Prime factors of 343: $343 = 7 \times 49 = 7 \times 7 \times 7$.

Prime factors of 216: $216 = 2 \times 108 = 2 \times 2 \times 54 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 27 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 3 \times 3$.

The prime factors of 343 only include 7. The prime factors of 216 only include 2 and 3. They do not share any prime factors. Therefore, they are co-prime.

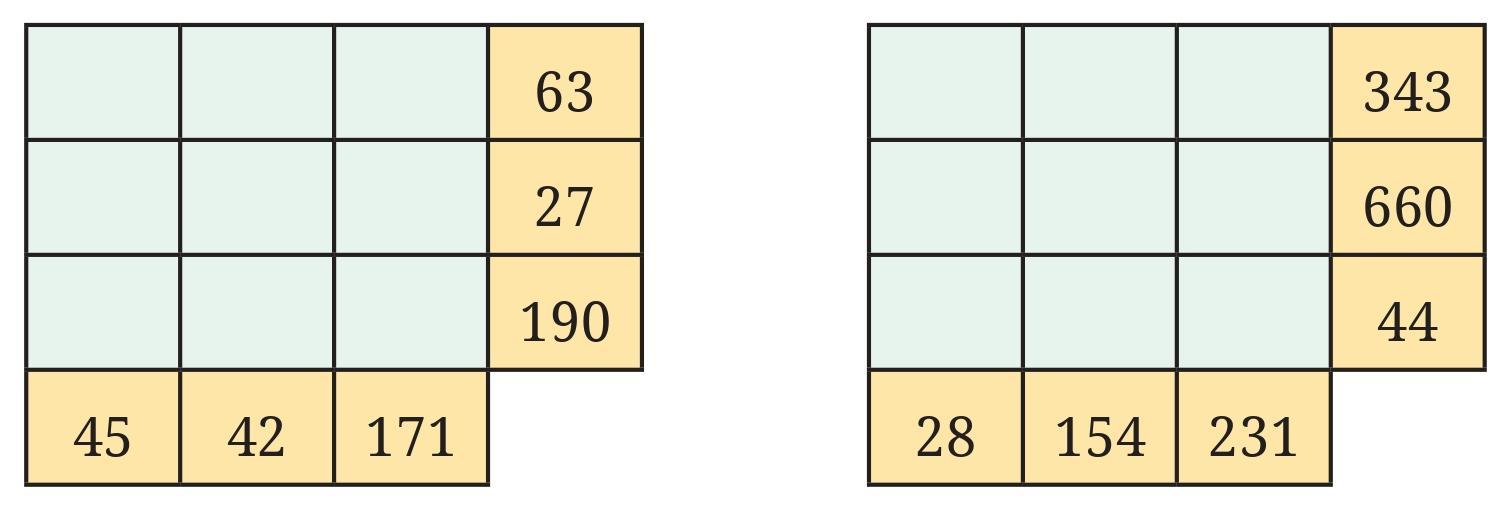

Question 2. Is the first number divisible by the second? Use prime factorisation.

a. 225 and 27

b. 96 and 24

c. 343 and 17

d. 999 and 99

Answer:

For one number to be divisible by another, all the prime factors of the second number must be "contained" inside the prime factors of the first number.

a. Is 225 divisible by 27?

Prime factors of 225: $3 \times 3 \times 5 \times 5$

Prime factors of 27: $3 \times 3 \times 3$

To be divisible by 27, the number 225 needs to have at least three 3s in its prime factors. It only has two 3s. So, 225 is not divisible by 27.

b. Is 96 divisible by 24?

Prime factors of 96: $2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3$ (five 2s, one 3)

Prime factors of 24: $2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 3$ (three 2s, one 3)

Does 96 have at least three 2s and one 3? Yes, it has five 2s and one 3. So, 96 is divisible by 24.

c. Is 343 divisible by 17?

Prime factors of 343: $7 \times 7 \times 7$

Prime factors of 17: 17 (it's a prime number)

Does 343 have a 17 in its prime factors? No. So, 343 is not divisible by 17.

d. Is 999 divisible by 99?

Prime factors of 999: $999 = 9 \times 111 = (3 \times 3) \times (3 \times 37) \ $$ = 3 \times 3 \times 3 \times 37$

Prime factors of 99: $99 = 9 \times 11 = 3 \times 3 \times 11$

Does 999 have at least two 3s and one 11? It has three 3s, but it does not have an 11. So, 999 is not divisible by 99.

Question 3. The first number has prime factorisation 2 × 3 × 7 and the second number has prime factorisation 3 × 7 × 11. Are they co-prime? Does one of them divide the other?

Answer:

Let's call the first number N1 and the second number N2.

N1 = $2 \times 3 \times 7$

N2 = $3 \times 7 \times 11$

1. Are they co-prime?

Two numbers are co-prime if they don't share any prime factors. Let's look at their prime factors:

N1 has prime factors {2, 3, 7}.

N2 has prime factors {3, 7, 11}.

They share the prime factors 3 and 7. Since they share prime factors, they are not co-prime.

2. Does one of them divide the other?

For one number to divide another, all of its prime factors must be present in the other number.

- Does N2 divide N1? N2 has the prime factor 11, but N1 does not. So, N2 does not divide N1.

- Does N1 divide N2? N1 has the prime factor 2, but N2 does not. So, N1 does not divide N2.

Neither number divides the other.

Question 4. Guna says, “Any two prime numbers are co-prime”. Is he right?

Answer:

Yes, Guna is right.

Here’s why:

Co-prime numbers are two numbers whose only common factor is 1.

A prime number is a number whose only factors are 1 and itself.

Let's take any two different prime numbers, for example, 5 and 11.

- The factors of 5 are just {1, 5}.

- The factors of 11 are just {1, 11}.

What is the only factor that appears in both lists? It's the number 1.

This will be true for any pair of different prime numbers you choose. Since they are prime, they don't have any factors other than 1 and themselves. Because they are different numbers, the only factor they will ever share is 1.

Therefore, any two different prime numbers are always co-prime.

Figure it Out (Page 125 - 126)

Question 1. 2024 is a leap year (as February has 29 days). Leap years occur in the years that are multiples of 4, except for those years that are evenly divisible by 100 but not 400.

a. From the year you were born till now, which years were leap years?

b. From the year 2024 till 2099, how many leap years are there?

Answer:

The rules for a leap year are:

1. The year must be divisible by 4.

2. Exception: If the year is divisible by 100, it is NOT a leap year... unless...

3. Special Exception: ...the year is also divisible by 400. Then it IS a leap year.

For example, 1900 was not a leap year (divisible by 100 but not 400), but 2000 was a leap year (divisible by 400).

a. From the year you were born till now, which years were leap years?

This answer depends on your birth year. To find the leap years, you can list the years that are multiples of 4 starting from your birth year up to 2024.

For example, if you were born in 2010:

The multiples of 4 after 2010 and up to 2024 are:

- 2012

- 2016

- 2020

- 2024

Since none of these years are divisible by 100, we don't need to worry about the exceptions. The leap years for someone born in 2010 are 2012, 2016, 2020, and 2024.

(You can find your own answer by starting with the first multiple of 4 after your birth year and counting by 4s.)

b. From the year 2024 till 2099, how many leap years are there?

We need to find all the multiples of 4 in this range. The year 2100 is the next multiple of 100, so we don't have to worry about the exception rule in this range.

Let's list them by counting in 4s from 2024:

- 2024

- 2028

- 2032

- 2036

- 2040

- 2044

- 2048

- 2052

- 2056

- 2060

- 2064

- 2068

- 2072

- 2076

- 2080

- 2084

- 2088

- 2092

- 2096

By counting the items in the list, we find there are 19 leap years from 2024 to 2099.

Question 2. Find the largest and smallest 4-digit numbers that are divisible by 4 and are also palindromes.

Answer:

A palindrome is a number that reads the same forwards and backward. A 4-digit palindrome looks like ABBA.

A number is divisible by 4 if the number formed by its last two digits is divisible by 4. For our number ABBA, the last two digits form the number 'BA'. So, 'BA' must be divisible by 4.

Finding the LARGEST number:

To make the largest number ABBA, we want 'A' to be as big as possible. The largest digit is 9.

If A = 9, our number is 9BB9. The last two digits are 'B9'. We need to find the largest digit 'B' so that 'B9' is divisible by 4. Let's check:

99, 89, 79, 69, ... none of these are divisible by 4.

So, A cannot be 9. Let's try the next biggest digit, A = 8.

If A = 8, our number is 8BB8. The last two digits are 'B8'. We want the largest 'B' that makes 'B8' divisible by 4. Let's check:

- B=9 → 98 (not divisible by 4)

- B=8 → 88 (divisible by 4, since $88 \div 4 = 22$). This works!

Since we used the largest possible 'A' (which is 8) and the largest possible 'B' for that A (which is 8), our number is 8888.

The largest number is 8888.

Finding the SMALLEST number:

To make the smallest number ABBA, we want 'A' to be as small as possible. The smallest digit for A is 1 (it can't be 0).

If A = 1, our number is 1BB1. The last two digits are 'B1'. We need to find the smallest digit 'B' so that 'B1' is divisible by 4. Let's check:

01, 11, 21, 31, ... none of these are divisible by 4.

So, A cannot be 1. Let's try the next smallest digit, A = 2.

If A = 2, our number is 2BB2. The last two digits are 'B2'. We want the smallest 'B' that makes 'B2' divisible by 4. Let's check:

- B=0 → 02 (not divisible by 4)

- B=1 → 12 (divisible by 4, since $12 \div 4 = 3$). This works!

Since we used the smallest possible 'A' (which is 2) and the smallest possible 'B' for that A (which is 1), our number is 2112.

The smallest number is 2112.

Question 3. Explore and find out if each statement is always true, sometimes true or never true. You can give examples to support your reasoning.

a. Sum of two even numbers gives a multiple of 4.

b. Sum of two odd numbers gives a multiple of 4.

Answer:

Let's test these statements with examples.

a. Sum of two even numbers gives a multiple of 4.

This statement is SOMETIMES TRUE.

Reasoning:

- Example where it is true: $2 + 6 = 8$. Here, 8 is a multiple of 4.

- Example where it is false: $2 + 4 = 6$. Here, 6 is not a multiple of 4.

Since we found one example where it works and one where it doesn't, the statement is only sometimes true.

b. Sum of two odd numbers gives a multiple of 4.

This statement is SOMETIMES TRUE.

Reasoning:

- Example where it is true: $1 + 3 = 4$. Here, 4 is a multiple of 4. Another example is $3 + 5 = 8$, and 8 is a multiple of 4.

- Example where it is false: $1 + 5 = 6$. Here, 6 is not a multiple of 4. Another example is $3 + 7 = 10$, and 10 is not a multiple of 4.

Since we found examples where it works and examples where it doesn't, the statement is only sometimes true.

Question 4. Find the remainders obtained when each of the following numbers are divided by (i) 10, (ii) 5, (iii) 2.

78, 99, 173, 572, 980, 1111, 2345

Answer:

We can find these remainders using simple tricks related to the last digit of each number.

| Number | (i) Remainder when divided by 10 (Just look at the last digit) |

(ii) Remainder when divided by 5 (Last digit divided by 5) |

(iii) Remainder when divided by 2 (0 for even, 1 for odd) |

| 78 | 8 | 3 (because $8-5=3$) | 0 (because it's even) |

| 99 | 9 | 4 (because $9-5=4$) | 1 (because it's odd) |

| 173 | 3 | 3 | 1 (because it's odd) |

| 572 | 2 | 2 | 0 (because it's even) |

| 980 | 0 | 0 | 0 (because it's even) |

| 1111 | 1 | 1 | 1 (because it's odd) |

| 2345 | 5 | 0 | 1 (because it's odd) |

Question 5. The teacher asked if 14560 is divisible by all of 2, 4, 5, 8 and 10. Guna checked for divisibility of 14560 by only two of these numbers and then declared that it was also divisible by all of them. What could those two numbers be?

Answer:

Guna is looking for the two most "powerful" numbers to check. If a number is divisible by these two, it will automatically be divisible by all the others in the list {2, 4, 5, 8, 10}.

Let's think about the connections:

- If a number is divisible by 4, it's automatically divisible by 2.

- If a number is divisible by 8, it's automatically divisible by 4 and 2. So, 8 is the most powerful check for evenness.

- If a number is divisible by 10, it's automatically divisible by 2 and 5.